Raw, real and unromanticized

The effect of growing up with divorced parents

Calista Kerba was in the second grade when she was given 10 minutes to make a decision that would alter the course of her life forever: choose to live with her mother or her father.

“All I remember of that day was that everyone was at home — my sisters, my mom, my dad — my sisters and I were all really confused when we were taken into our bedroom,” said Kerba. “They told us how we had to choose whether to live with my mom or my dad. We got 10 minutes to discuss what we wanted to do and who we wanted to live with.”

For as long as she can recall, junior Calista Kerba has had divorced parents. Kerba was primarily raised by her grandparents; her mother had moved to New Mexico to steer clear of any custody-related issues that may have arisen with the separation, and her father was often absent due to his demanding job as a dentist.

Typically, as in Kerba’s experience, news of a divorce without much context evokes immediate shock, confusion or fear of the unknown. In other cases, however, children are not surprised when their parents make the announcement. Unlike Kerba’s unforeseen exposure to divorce, some children begin to notice a rather discordant family dynamic or unfamiliar tension that may foreshadow a separation in the future.

“[My parents] separated in my freshman year,” junior Rosemary Howley said. “It wasn’t a surprise to me. When I was in elementary school, I had suspicions that they would be getting a divorce, and I just hated the idea of [not living with both parents] so much. It was overwhelming.”

Divorce usually divides a family into two households, resulting in the children of divorcees choosing a parent to live with, but the living situations of children vary from family to family. While some children, like Kerba, will choose to live with one parent, others may opt to alternate between their parents’ houses, both of which are options that may seem daunting. Children who settle for the latter must accustom themselves to an entirely new family dynamic, which for a while may provoke instability and insecurity, with the underlying notion that they cannot be with one parent without having to be apart from the other.

There are two basic types of custody that must be accounted for in any scenario involving child custody: physical custody and legal custody. Legal custody refers to the parents’ responsibility of making decisions for their child while they are still a minor, and encompasses decisions regarding schooling, religion, housing and counseling. Under the umbrella of legal custody lies joint legal custody and sole legal custody. Joint legal custody implies that both parents have legal responsibility to decide on those decisions, while sole legal custody implies that one parent is solely responsible for making decisions on behalf of his of her child. Physical custody establishes where the children will live on a regular basis. Granting a parent sole physical custody relays a vast amount of power to that parent, as he or she can legally move across the country without informing the other parent, assuming all other tenets of custody are being followed. Granting parents with joint physical custody would establish the cooperative involvement of both parents in their children’s lives.

In the time following a divorce, the dynamic of a child’s family life may change drastically. Marital disruptions typically worsen the relationships between the parents and their children, yet some children may find themselves developing a more personal relationship with their parents that did not exist prior to the divorce. When divorced parents no longer have each other to turn to, they often rely on their children to have meaningful cons with.

“Sometimes, when I was with my dad, I really didn’t want to be there. I just wanted to talk to my mom,” said sophomore Analiza Smith*. “But sometimes when my mom and I get into an argument, I usually want to talk to my dad, so it’s kind of difficult. However, I spend half of the week in each house, so it’s equal.”

According to a study conducted by Verywell Family in April 2018, approximately 50 percent of American children will witness their parents’ divorce before they turn 18, begging the question: how is the psychological well being of a child impacted by their parents’ separation?

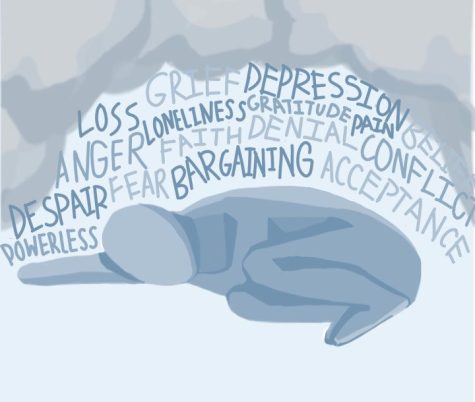

An analysis conducted by the National Survey of Children, which examines the physical and emotional health of children under 18, David Popenoe, a professor of sociology at Rutgers University, concluded that mental health issues such as depression, aggression and withdrawal are often associated with children who have previously been exposed to a divorce. Popenoe observed that divorce contributed to mental disorders or illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder and dysthymia, a persistent mild depression. The younger they are, the more children tend to be reliant upon their parents’ care, so young children whose parents divorce are often more vulnerable.

“The older you are as a child or young adult with divorcing parents, often, you get told more information from the parents going through the split as opposed to what much younger children are told,” said school psychologist Dr. Brittany Stevens. “Parents may desire to not let their young child in on their conflicts. They are often more protective of younger rather than older children.”

Despite the considerable changes in a child’s life following a divorce, parents separate because they do believe their marital relationship will be more harmful than beneficial. Focusing on the positives, such as less familial conflict or a more cooperative family dynamic, may improve a child’s emotional well being and ease the rather unpleasant aspects of divorce. Kerba encourages these who find themselves facing divorcing parents to keep a few things in mind.

“Focus on the fact that your parents created you, they love you,” Kerba said. “Think about everything they’ve done for you. Recognize how they’ve devoted half their life to you.”

*names have been kept anonymous for privacy reasons

Belinda Zhou is currently a junior and the Opinion section editor for the Epic. She enjoys singing along to all the lyrics of "Fergalicious", hanging out...

Diana is a senior and the Managing Editor of the Epic. This year, she hopes to grow close with the staff and have fun at socials. She loves listening to...