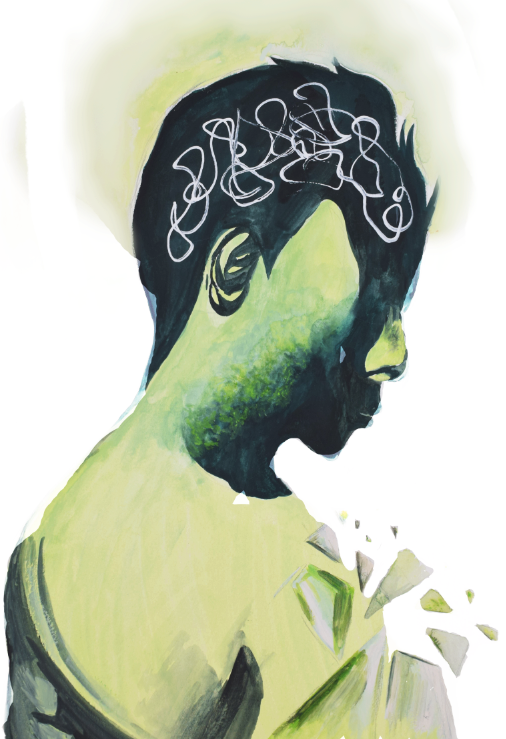

The reality of mental health for the model minority

With more than 50 distinct individual races and ethnicities and more than 30 languages spoken, the Asian-American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community is the fastest-growing and most diverse racial and ethnic group in the U.S. Such diversity lends itself to a plethora of cultural influences on mental health. In a recent survey sent to Lynbrook students, 60 percent of individuals felt that being Asian-American influenced their mental health; of those individuals, the most common sources of stress were parent and peers.

“As most Lynbrook students know, being Asian-American influences everything: who we are, what we do, what we eat,” said sophomore Jordan Lee*. “At the core of it all is our parents and their beliefs; these expectations build up over time and begin to feel confining, leading to frustration and anxiety due to factors such as pressure and achievements, among others.”

In a 2007 study conducted by the University of Maryland School of Public Health research team, Asian-American participants reported that the primary sources of stress included parental pressure to succeed in academics and uphold the “model minority” stereotype and the impression that mental health concerns are too taboo to discuss with their families.

In some Asian cultures, education is highly valued, and children who do not exceed academic expectations can be seen as shameful. For example, Confucianism, an ideology created by the Chinese philosopher Confucius, places a heavy emphasis on education. In several Asian countries, a traditional classroom education is supplemented with intense after-school tutoring.

“Asian society’s view on children is they have to be successful,” said junior Avery Chen*. “Parents always want to be able to brag about their child. With the pressure of being a good parent getting mixed up with your child performing well, it creates a stigma around being Asian that your self worth is determined by the grades you get, your academics or your extracurriculars.”

Moreover, stress from the “model minority” stereotype adds to the high educational expectations for Asian-Americans. Asian-Americans are often associated with the “model minority” myth that Asian-Americans are socioeconomically better off than other minority groups and are expected to set the standard for other minority groups to aspire to. Stereotyped as hard-working, passive, quiet and smart, Asian-Americans are often inherently assumed to be high achievers. AAPI individuals are thought to have overcome racial bias and are perceived to be less in need of assistance and resources than other minority groups.

“I hate the term ‘model minority’ because it assumes that a group is in the same position as those with privilege, and that other minorities should look to us as the ultimate example of what they should be,” said Derek Zhou, a senior at Palo Alto High School and a member of the Santa Clara County Youth Advisory Group on mental health. “Moreover, the term ‘model minority’ negates the genuine issues that plague the Asian community.”

Although perceived as a positive stereotype by many, the myth has a devastating effect on the psychological wellness of AAPI individuals. While AAPI and Caucasian communities have similar rates of those with diagnosable mental illnesses, little research has been conducted regarding mental health in the AAPI community.

Those struggling with mental health within the AAPI community are three times less likely to seek mental health services than Caucasians. While the “model minority” myth plays a significant role in this statistic, a 2010 study in the American Journal of Public Health noted that the most deterring factor was the negative stigma surrounding mental health in Asian cultures and a lack of awareness of mental health resources.

“There have been times when my mom has said, ‘fine, I’ll get you a therapist.’ But it is always in a derogatory way; it is always out of anger. She thinks I can just solve the issue myself or ignore it,” said sophomore Amy Sun. “Yes, there are resources at school, but you have to feel like you yourself can reach out first. When you need professional help, but do not know how to reach out or recognize that you need it, it feels like there are not any available resources.”

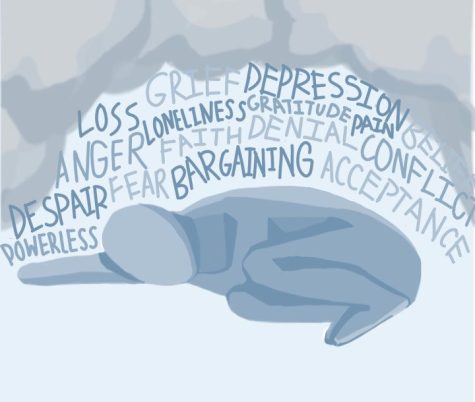

Mental health issues in Asian cultures may be caused by the expectations for each individual. Children and adolescents are brought up to be humble, obedient and polite: they are expected to meet and conform to traditional behavioral standards, and emotional outbursts are discouraged. By learning to suppress emotions from a young age, AAPI children are at a higher risk for mental illness by being unable to recognize negative emotion or reach out for help.

“The most common misconception is that Asian Americans don’t have mental health issues,” Zhou said. “Though I can’t speak for all Asians, I have grown up in a Chinese-influenced environment for my whole life; this has definitely influenced my attitude toward mental illness. A lot of this comes from Chinese culture, which pressures you to live in balance and honor your family. When a topic that doesn’t align with these values comes up, it is immediately ignored. In this way, a lot of Chinese people internalize their feelings.”

In many Asian cultures, mental health struggles are perceived as not only a reflection of the individual, but of the family as well. Traditional Asian values place heavy emphasis on family image; consequently, opening up about mental illness brings shame to the family. Additionally, in numerous AAPI cultures, mental illnesses are traditionally believed to be caused by lack of harmony in emotions or by evil spirits. In Buddhism, problems in one’s life are thought to be related to offenses committed in one’s previous life. Philosophies stemming from Confucian beliefs discourage one from publicly displaying emotions to maintain familiar harmony and prevent being viewed as weak. The stigma created through these beliefs leads Asian-Americans to dismiss, deny or neglect symptoms. The treatment for these issues include home remedies, traditional herbs or acupuncture. Reaching out for professional help is avoided, as it affirms the severity of the illness.

“Stigma and ignorance in the AAPI community is dangerous and costs lives by delaying treatment,” said Helen Hsu, a staff psychologist at Stanford University specializing in the Asian-American population. “Prognosis is always better when things are addressed as soon as possible. I have heard countless people delay treatment due to myths and misunderstandings. We need to create a community where it is okay to talk about mental health and never blame families or people who fall ill.”

Outside of the cultural stigma surrounding mental health in AAPI communities, Asian-American and Pacific-Islanders face additional obstacles to receiving help. Many mental health resources are offered only in English, erecting language barriers and making it increasingly difficult for Asian-Americans and Pacific-Islanders to access mental health services. According to the American Psychological Association(APA), half of the Asian-Americans suffering from a mental illness will not seek help due to language barriers.

Additionally, due to inattention to mental health among Asian-Americans, there is a severe lack of AAPI professionals in the mental health field. For example, according to the APA, in 2002 only 2.3 percent of ninety-thousand doctoral level psychologists were Asian. With little research on Asian-American mental health, only the small population of AAPI practitioners tends to be the ones familiar with this literature.

“Eighty-three percent of the psychologists in this country are white,” Hsu said “We have a serious shortage of [AAPI] practitioners, professors and researchers with the cultural competency or language and cultural knowledge [to discuss mental health with members of the AAPI community]. This is improving slowly, but there is a supply and workforce development problem. In the past, this has contributed to our community being neglected as AAPI needs were rarely even mentioned in research.”

Even within the AAPI community, the broad scope of the Asian-American identity leads to several different cultural influences on mental health. The unique immigration experiences of each AAPI cultural group can lead to several cultural contexts behind mental health issues. While many Asian-American teens in the Silicon Valley experience mounting pressure to excel in a science, technology or mathematics careers, those who entered the U.S. as refugees from the Vietnam War encountered various traumas, making them more susceptible to suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. While both communities are afflicted by mental health issues, they hold differing cultural circumstance for the cause of mental health issues. Children of Asian-American immigrants often feel pressure to make up for their parents’ sacrifices in immigrating to the U.S. For many, this surfaces in an overwhelming pressure to relieve their parents’ financial burden by making enough money to support both themselves and their parents. For others, it means living up to the precedent set by a highly successful parent who experienced the additional challenge of immigration.

“Both of my parents are immigrants, so I feel the pressure to live up to what they have done and achieve more because I am an American citizen, something they planned to make it easier for me to gain access to more opportunities,” said senior Sam Gupta*. “At the end of the day, the Asian experience of ‘how I made it to America’ still influences the choices of first generation kids. “

All factors considered, there is a striking deficit of mental health resources that understand and respond adequately to the impacts of Asian-American cultures and the “model minority” myth on AAPI individuals’ mental health.

“Schools, counties and hospitals do not make sufficient efforts to recruit and promote AAPI staff,” Hsu said. “The ‘model minority’ myth still causes this population to be ignored in needs and assessments. Our own community makes the matter worse by hiding problems due to stigma. If we hide the problem, we do not get any research nor funding. AAPI communities need to speak up about our needs and push for the right kinds of services and support.”

Although the AAPI population faces a lot of unacknowledged barriers, it is not to say that AAPI individuals have the worst mental health in regards to other races.

“Yes, [AAPI individuals] do have it hard. Yes, we do have pressures,” said senior Shiva Patel*. “But we need to understand that everyone is different. Everyone has different backgrounds, everyone has different sets of values, and whatnot, and those all contribute to the mental health that we have to go through. It’s just that the reasons that the symptoms come out is because we have different contexts and different backgrounds that make it come out.”

*names have been kept anonymous for privacy reasons

As a Singaporean-American teenager passionate about politics, American History, and social justice, Nicole aims to reflect these passions in her writing....