Changing the face of Western masculinity

When outdated social expectations become toxic

It is 10 p.m. on a Friday night. A boy shrugs off his backpack, exhausted after a long session at the gym with his friends, during which they competed to see who could bench the most weight. Slipping off his shoes, he turns on the TV, ready to unwind with a quick round of “Battlefield” when he sees another report of a shooting. The suspect is yet another male with a gun, and the news cites video games as a primary cause of the shooting. The boy promptly drops his controller. He wonders why society pushes him to embrace his masculine qualities, yet also tells him to suppress them.

The American definition of masculinity finds its roots in the hunter-gatherer roles of primitive male homosapiens: to be masculine means to be physically strong, aggressive and competitive. This “alpha” ideal, thought to be the pique of masculinity, has only been further enforced in recent years, as most common examples of masculinity are limited to brawny athletes, charismatic actors and virile sex-symbols. Recent news regarding violence and sexual harassment, however, have begun to paint such qualities as negative and undesirable.

Though politicians cite mental illness as one of the leading causes of mass shootings, the truth lies in the statistics: only 14.8 percent of mass shooters have been linked to mental illness. Comparatively, the proportion of male to female shooters has been much larger: only three out of the recorded 98 shootings since 1982 having been committed by women, thus raising suspicion among some individuals that a possible cause of recent shootings may be a societal bias rooted in an outdated definition of masculinity rather than medical issues.

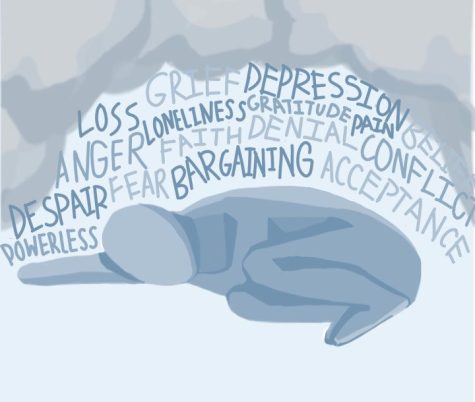

Statistical and criminal evidence reinforce a possible link between traditional masculinity and mass shootings. Reportedly, 30 percent of shootings take place in office settings by a discontent male employee. The 1991 shootings in Michigan and New Jersey workplaces, for example, were led by men who felt that they were owed employment. Elliot Rodger, University of California, Santa Barbara shooter, published a video titled “Elliot Rodger’s Retribution,” where he expressed a lack of romantic and sexual reciprocation and threatened to “punish,” “slaughter” and take “revenge on humanity.” The result of such evidence culminates in a concept called “toxic masculinity,” a phenomenon in which social expectations restrict expressions of one’s masculinity to aggression and shows of dominance, standards that haven’t changed much throughout history.

“Men are expected to be leaders, tough, physically strong, dominant, unemotional and assertive, to name a few,” said Alison Dahl Crossley, Associate Director of Stanford’s Clayman Institute for Gender Research.

The Western culture that restricts the domain of male identity to specific physicalities, sexualities and interests is also prevalent in a media that perpetuates the cultural construct of masculinity. For instance, advertising may isolate the perception of masculinity to a rigid, conservative male ideal.

While female-targeted advertising has recently taken a new form in embracing non-traditional beauty and bodies, male-targeted marketing lags behind. Male lifestyle magazines such as Men’s Health and Maxim continue to enforce stereotypical male tropes and hegemonic masculinity. Advertisements for beer convey tones of male camaraderie, and certain motor vehicle commercials are deeply gendered to target ideas of physical strength and adventure.

Film and media have played increasingly large roles in defining the masculine identity through violence. Post 9/11 cinematic portrayals of maleness led to the emergence of hyper masculinity, homophobia and misogyny. Violent ideology permeating the cinematic space was considered by many critics to be a reaffirmation of male self-actualisation. Typical male archetypes produced a newfound masculinity portrayed as heroic, heterosexual and stoic with a strong sense of machismo and purpose.

The popularization of superhero films such as “Spiderman” and”Hulk” accentuated stereotypical male ideals, while “Forgetting Sarah Marshall” and “Hot Tub Time Machine” iterated that remasculinization is necessary for successful relationships. Even romantic comedies, such as “Knocked Up” or “Superbad,” where more eccentric or effeminate male characters triumph in love, are problematic by pushing the notion that non-conventional males must prove themselves in alternative ways to the standard machismo men in order to win over their love interests.

In contrast, feminine standards have transformed several times throughout the past two centuries. From Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Seneca Falls Convention discussing women’s suffrage in the 1800s to 2017’s first Women’s March fighting for equal rights and representation of all minorities, women have had an abundance of prominent female figure heads who challenge what it means to embrace one’s femininity.

However, the same cannot be said for all males. The exploration of gay and intersectional rights for male minorities in more recent years have brought about reform with the manner in which members of the LGBTQA+ community are perceived and portrayed in media.

In 2016, Covergirl was applauded for the inclusion of the first male makeup model. On Youtube, a rise in male beauty and lifestyle influencers have continued to break down boundaries and expectations for the perception of male presence in traditionally female industries such as the fashion and lifestyle industries, however have yet to dissolve the generalization that such individuals are also members of the LGBTQA+ community.

In recent years, male beauty products have expanded into a lucrative market with the metrosexual man as its face. Metrosexual men are defined as heterosexual males who tend to be more meticulous with their appearance and more willing to dedicate their time and money toward self grooming. Rather than opposing traditional masculinity by selling more conventionally female products, metrosexual products, such as fragrance and lotions, are advertised by men with visual strength and virility, bridging the gap between traditional maleness and the perception of effeminate behaviors.

Pop culture today is reevaluating what it means to be masculine. Traditional gender perception is beginning to question the existing dichotomy, and the conventions expected are increasingly challenged. The definition of masculinity is becoming increasingly less concrete, less reliant on merely physical and emotional traits or rigid ideals that brutalize outliers. With the greater integration of homosexuality in society, effeminate men are less often considered inferior.

“I feel like its kinda silly to have any definitions whatsoever. I don’t think there should be a definition. Its kinda silly that there has to be a definition of masculinity. ” said Wang. “If there is a push for change at all, there should be a push to say ‘do whatever you want’ rather than redefine what it means to be masculine because I feel like once you redefine it, like saying ‘its bad ‘ to think men are supposed to be big and hairy, and ‘to be small and skinny,’ then all the big and hairy people feel kind of left out. So yes there should be a push, but no, not a push to redefining masculinity.”

Michyla Lin is the Design Editor of the Epic. She's responsible for all the "aesthetics" of the paper and website, including drawings, graphics, layout...

Julian • Feb 11, 2021 at 2:29 pm

Well yeah look at a typical front cover of an American Men’s Health magazine and a Men’s Health magazine from South Korea, a huge difference. I also notice that in mainstream Western action movies, if the male lead is anything other than the manly stereotype, he’s depicted as either nerdy, gay, or incompetent. Usually this backwards mentality runs rampant in small towns or certain areas where men don’t have too many options in life.

pacificah okemwa • Nov 15, 2020 at 9:45 pm

Hi I really love your article. Kindly allow me to use the image in an online lesson on masculinities

Jared • Jul 20, 2019 at 2:56 am

Maybe if we actually raised boys to become better men with male/father figures, instead of letting brain-dead feminists brainwash our boys by suppressing their masculinity, we wouldn’t have so many shootings. If these shootings have only become common in the last 30 years, it’s clearly not an “outdated” form of masculinity causing it. It’s clearly a newly socially constructed feminist version of masculinity that suppresses who boys and young men truly are.

Also, some men do some terrible sh*t. But the painfully obvious fact is that men have also done nearly everything that has made society great, safe, and advanced. Just like with women, you have to take the bad ones with the good. I suggest feminists grow up about their insecurities toward men.