Academic pursuit in a post pandemic classroom

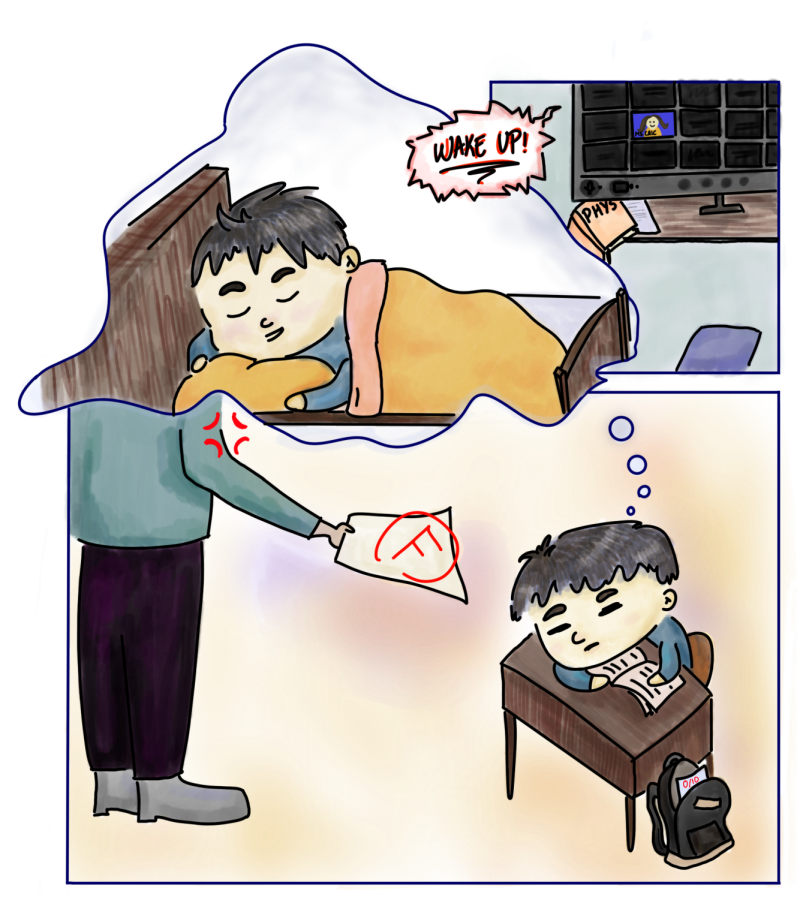

A comic depicting students carrying over pandemic-era study habits back with them into in-person learning. Graphic illustration by Sarah Zhang.

November 7, 2022

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, some teachers supported distracted students with accommodations including lighter course loads, extensions for late work and adjusted expectations overall. Although it has been two years since students have returned to in-person learning, many expect the same treatment. These lingering study habits are concerning, as they don’t effectively train students to adapt to future challenges. While teachers can aid students by striking a balance between engagement and rigor, students also must shift their mindsets to genuinely engage in the classroom.

Lynbrook has always prided itself on rigorous learning standards, of which its students are expected to uphold. Yet according to recent CAASPP data, both math and language arts scores of non-economically challenged FUHSD students declined from 2020-22.

“The Bay Area grindset is motivating but also negative,” Lynbrook alumni and MIT freshman Albert Tam said. “My peers were doing so much, which encouraged me to participate in more activities, and I’m happy with what I did. That being said, the culture can definitely get toxic.”

During the 2020-21 school year, teachers were teaching black boxes of names on Zoom. On the other side of the screen, students often engaged in non-school related activities. With digital turn-in conversions, students increasingly skirted academic honesty policies. Sharing academic materials over the Internet became more prevalent, with sites such as Chegg reporting a 67% subscriber increase in 2020 from the previous year. This means students were relying on possibly misleading or outdated information, foregoing the learning process.

Leniency in grading is another factor that incentivized students to slack off. In July 2021, the State of California passed legislation allowing students to request “Pass” or “No Pass” grades in their classes in lieu of the traditional letter grades. A “Pass,” which replaced everything above an F, eradicated many students’ drive to work for a higher letter grade.

This lower desire for achievement contributed to a vicious cycle of non-participation and dropping grades, affecting those who were unprepared for the return to structured academics. It is thus crucial that students shake off their pandemic sluggishness.

“It is a problem if you’re constantly limiting yourself to what’s most convenient,” senior Sophia Das said. “By repeatedly choosing the easy way out, you’re going to stunt your growth and responsiveness to change.”

Students should not continue to expect the same treatment from their teachers, especially as many are missing a large chunk of what was previously thought to be basic knowledge.

“I have to spend more time on founding documents than I normally would have, because they weren’t necessarily delved into due to remote learning,” AP U.S. History and World History teacher Kyle Howden said. “It takes up more time, whereas traditionally I wouldn’t necessarily have to go into as much depth.”

As teachers make a conscious effort to fill in these learning gaps to build a foundation for future learning, students should likewise strive to develop proficiency in what they are taught. Though it is unreasonable to expect students to be completely unfazed after a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic, students should be open to learning, rather than slipping back into pandemic torpor.