CUSD tables school closures but has no long-term solution in-place

Graphic illustration by Diana Kohr

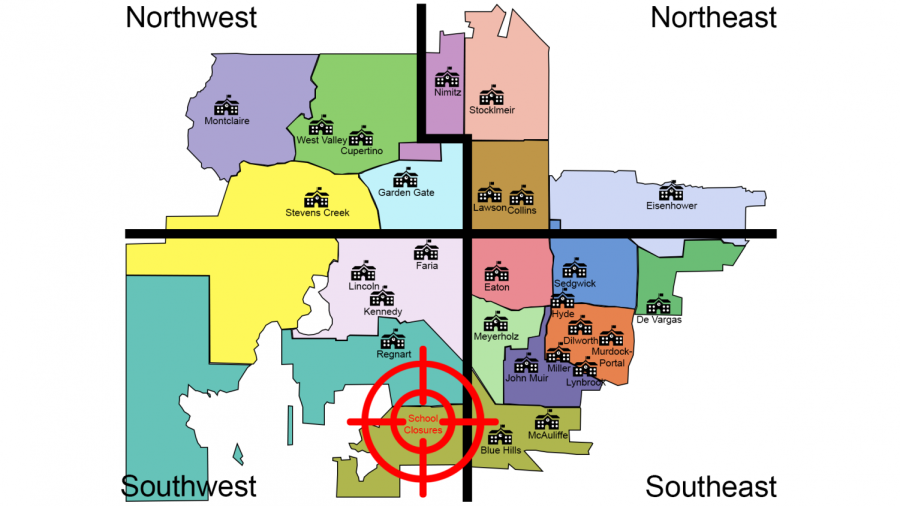

Elementary and middle schools in each of the four quadrants in the CUSD map.

December 9, 2020

To address a budget deficit and declining enrollment, the Cupertino Union School District (CUSD) has recently been forced to consider shutting down schools, outraging community members and sparking community efforts to “save all CUSD schools.” Currently, the district has tabled school closures and is waiting to see whether or not a proposed parcel tax will pass in spring 2021 before taking further action.

The district’s budget issue stems from the limited state funding that it currently receives. There are two main funding models for public schools in California: a combination of property taxes and state funding or property taxes only. If the district’s per-student revenue from property taxes exceeds the minimum threshold set by the state, it does not receive state funding and gets to use any additional revenue from property taxes.

However, if a district’s property tax revenue is not sufficient, they depend on the state to supply the remaining funds. This model applies to CUSD and makes their finances highly dependent on enrollment, as the state provides funding per student.

Unfortunately, CUSD has experienced declining enrollment for six years, and the projected number of students in the 2020-2021 school year is 16% lower than that of the 2013-2014 school year peak. Projections are based on the district demographer’s conservative report, and the trend of declining enrollment is predicted to continue through the 2024-2025 school year, the furthest the prediction goes.

Furthermore, each district that receives state funding begins with the same base amount per student, but the state adjusts that amount depending on how many high-need students the district has. CUSD receives less funding per student because it has fewer high-need students, which includes students of lower socioeconomic status, English language learners and foster and homeless youth, than other school districts. Made up largely of families who come from affluent backgrounds, CUSD has fewer high needs students compared to other districts. Even compared to other local districts, CUSD has a lower number of high-need students, which results in lower per-student funding from the state.

“There are districts that we share borders with that have $2,000 to $7,000 extra per student per year,” CUSD Board President Lori Cunningham said. “Everything a school district does has costs associated with it, and we have far less funding than any other district anywhere. Yet we are still expected to provide the same excellent education, and we are very proud of the fact that we do.”

In fact, according to Cunningham, CUSD is one of the lowest government-funded school districts in the county, state and nation. On average, the district receives about $4,000 less per student per year than both the California and national average.

In addition to limited state funding and declining enrollment, CUSD was also expecting a large budget cut from the state. CUSD’s budget reports are available to the public on the budget reports page of the CUSD website. These predictions are based on the governor’s budget proposals, which were released in May 2020.

The 2020-2021 budget adoption document reflects the governor’s proposed $10 million cut in state funding to the district, leaving CUSD with merely $207 million for the 2020-2021 school year compared to the 2019-2020 school year’s projected revenue of $217 million. This year’s reduction in revenue strays from the recent trend, as revenue projections have been relatively similar for the past three years.

The decrease in revenue forced the district to adjust expenditures, so it could maintain a positive balance to serve as a buffer for following years. The ending balance is typically around $21 million, so the district reduced projected expenditures by $9 million to balance the $10 million cut. One solution to address the decreased funding was to close schools.

However, the final CUSD budget changed between May and July to reflect changes made when the state legislature finalized the budget in July. The finalized budget has much fewer cuts than the governor’s proposed budget; nevertheless, the district still faces the long-term issue of low state funding. If the district does not act on its budget issues, it risks becoming insolvent, which essentially means bankruptcy for the district. If the district nears insolvency, the state gains full control of the district’s budget.

“We actually have to have a balanced budget by law,” said Mark Loundy, School Site Instructional Technology Specialist at DeVargas Elementary School. “If the district was to just let itself go into default, we’d be taken over by the state. Then, someone from the state would come in and make essentially the same decisions that we had to make, but without the community feel that we have.”

School closures have been considered as a potential solution because they alleviate significant financial burden; each closure could save the district $1.3 to $1.4 million dollars a year. However, parents who have analyzed the district’s budget reports argue that the financial concerns are not significant enough to close schools.

“In my opinion, [the current budget] is not a huge problem. Relative to their large budget, the district is only a few million dollars short,” said Peng Liu, a Meyerholz Elementary School parent involved in a Save Meyerholz event. “One of the moves the district board is considering would close 10 out of the 25 elementary schools. That is not reasonable because the budget gap is so small, and the impact of closing so many schools is huge.”

Because state funding is based on school size and many schools’ enrollment numbers are below ideal, the CUSD Board formed the Citizens Advisory Committee (CAC) in early 2020 to explore different options. The CAC consists of community stakeholders, parents and staff, from each school in the district. For example, Loundy is a staff stakeholder representing DeVargas Elementary School.

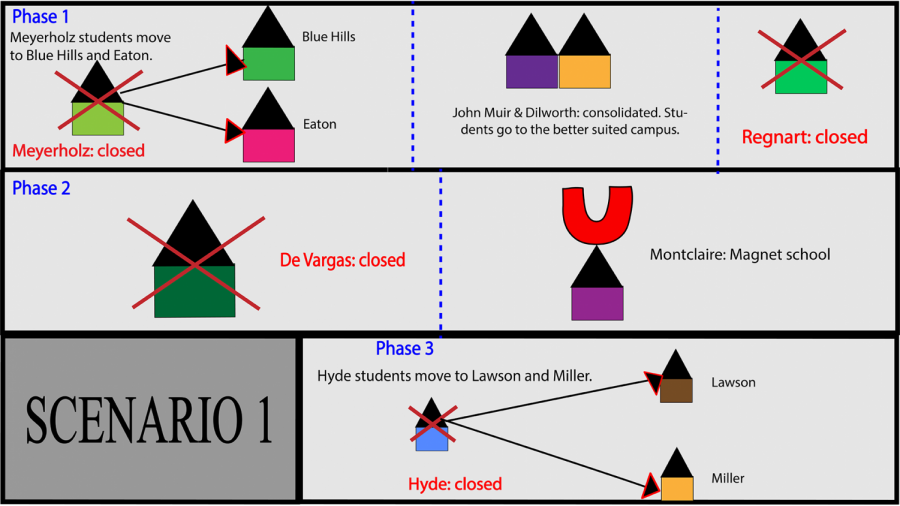

The CAC was then given a set of criteria by the district to follow when formulating their proposals. The CAC charge and driving principles state that it will inform the board about closing schools and suggest long term plans to achieve fiscal solvency and balance enrollment. In order to explore all options, the CAC divided into four working groups. In total, six scenarios were presented to the district board. While the scenarios are highly specific, they are meant to be hypothetical options for the district to explore rather than plans of action.

Some scenarios create magnet schools, schools with special courses, to attract students from outside the school’s original boundaries. In addition, as specified in the Board’s criteria, the Chinese Language Immersion Program (CLIP) will be given its own campus.

Concerned parents voiced their opinions at CUSD Board meetings and argued that the district has not been transparent enough with the community. Some were frustrated with the lack of communication from the district, as an email was sent to parents about applying for the CAC in February 2020, but the purpose of the committee was undisclosed.

“Parents are uniting together, doing car rallies and talking with the district Board members,” Liu said. “We are also looking for other sources of money to help the Board fill the budget gap. However, the Board is hesitant to take the money. Their statements are not consistent from time to time. Sometimes they say, ‘This is fine; we can accept your donation or donations from big companies, but sometimes they say that those one time donations cannot be counted as a long term budget source. So the whole process is not very transparent at all.”

Those opposed to shutting down schools also note that the change could impact travel times and spur relocation to find better schools. Many parents also worry that school closures will break friendships and destroy familiar learning spaces.

“My kid loves Meyerholz,” Liu said. “The school is the center of our community, and the center of [life for] our kids. He has a lot of friends there. It is unfair to separate those friends.”

Because schools like Meyerholz feed to Miller Middle School, parents fear that closures would affect the middle school a student attends.

“My son may not be impacted as he will be done with elementary school and will go to Miller; however, it does theoretically affect the possibility of him going to Hyde instead of Miller,” parent Srividhya Venkataraman said.

High schools, on the other hand, will not be affected as FUHSD boundaries are independent from CUSD. One possible exception is CLIP, because CLIP students do not have to be within the district’s boundaries to attend Miller Middle School and Lynbrook High School.

By rezoning the district, housing prices may decrease and disrupt the neighborhood dynamic.

“Some of the neighbors do not have kids going to school right now, but even if they’re older senior citizens, the next generation might be going to the school,” Liu said. “They might want to sell their houses, so they can enjoy their retirement elsewhere. This change will have a significant impact on their plan, their life plan—there will be a significant impact on everybody.”

As of now, school closures have been tabled, and CUSD has confirmed that no schools will be closed in the 2020-2021 school year. To address the funding shortage, the district will push for a parcel tax in May 2021 that will provide additional funding, like that of Measure M for FUHSD, if passed and potentially prevent school closures.

“I am not in favor of closing schools for financial reasons,” said Jerry Liu, CUSD Board Vice-President. “The problem with our district is that we’re underfunded, not because we’re spending too much on our kids. I work in corporate management, so in my way of thinking, if we’re underfunded, let’s try to fix that problem first. If that doesn’t work, then you try to do these other things. I am just not in favor of closing schools for that $1.4 million [per school]. We really should address the revenue side first before we go into the cost side.”

However, parents worry that the solution may be temporary: if it passes, the district will not close schools for another three years, but closures might become a possibility in the not too distant future.