No green light to green card for visa holders

December 9, 2020

Adobe Spark by Anusha Kothari and Priyanka Anand

Read the story above in the Adobe Spark or below:

Introduction

After ten years of tension and uncertainty, Class of 2018 alumnus Daniel Lee* and his family received green cards in April 2018, finally transitioning them from H-1B and H-4 visa holders to permanent residents. They initially moved from South Korea to the U.S. when Lee was just nine years old, searching for economic and educational opportunities.

“I received my green card on my birthday, so that was really cool,” Lee said. “My family was really shocked because we had been waiting for 10 years. We were really happy.”

In the years leading up to receiving their green cards, the ambiguity surrounding their status in the country permeated every aspect of Lee and his family’s lives, from socioeconomic stability and familial relationships to Lee’s academic pursuits. As low-income visa holders, Lee’s family worried that receiving public health insurance would affect their green card application and thus remained uninsured until becoming permanent residents. Lee also recalls that before receiving their green cards, the additional pressure on his family members strained their relationships.

“It is so true that your visa status or socioeconomic status can ruin your family,” Lee said. “I think my family was an example of that—we just didn’t have the luxury to love each other or do the “happy family thing” because we were all so sensitive. My parents were fighting a lot and there was a lot of tension between my family members at the time.”

Lee’s immigration status also limited his academic opportunities, preventing him from attending his dream school due to the lack of financial aid available to students in his situation. Additionally, the nebulous nature of his immigration status and the long wait to receive a green card affected his interactions with his peers.

“I was really insecure about my visa status and my family’s financial situation, so I would lie about my status to friends,” Lee said. “A lot of students go to other countries during the summer but I couldn’t go because it’s not recommended to leave the country when applying for a green card. I would [tell my friends] I’m not going because of some other reason.”

Lee is just one example of many H-1B and H-4 visa holders in the Lynbrook community, and his story is one of millions across the country. Although no two people share the same experience, the green card application process comes with benefits and challenges for all H-1B and H-4 visa holders.

*name kept anonymous for privacy reasons

H-1B and H-4 visas

H-1B visas are provided to foreign workers in specialty occupations, which require a minimum of a bachelor’s degree or the equivalent in work experience in specialized fields. Companies apply for and secure its workers’ H-1B visas, which are valid for three years before workers need to petition for renewal.

Launched with the passage of the Immigration Act of 1990, the H-1B visa program was initially established to help American firms minimize labor shortages in rapidly-growing fields such as research, engineering and computer programming. Even now, the most popular occupations for H-1B workers in the U.S. tend to be STEM-related, with 42% of H-1B holders being computer professionals. Hence, American and Indian technology companies Cognizant, Tata Consultancy Services and Infosys provide the three highest numbers of H-1B visas. Relying on labor from H-1B workers rather than only from permanent residents and American citizens allows companies to save money, as H-1B workers are often paid less.

“Companies show interest in H-1B visa-holders because they bring talent, expertise and specialization,” said Annapurna Pandey, Professor of Anthropology at UC Santa Cruz who has performed extensive research on immigration. “H-1B workers can contribute, and they are the ones who help companies like Facebook, Google and Salesforce make profit and help swell the economy.”

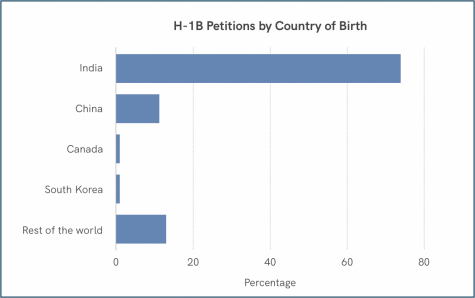

Every year, H-1B visas are issued to a limited number of applicants, with 65,000 as the cap in 1990. However, numbers have gradually grown over the past two decades, with 180,110 workers receiving the visa in 2019. While the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was the first legislation to expand immigration to countries outside of Europe, including those in Asia, the establishment of the H-1B visa program in 1990 is largely responsible for the high number of Asian immigrants in the U.S. As there are a large number of engineering and technology workers on the H-1B visa, the visa is increasingly provided to people from

India and China, countries that emphasize STEM education. Data from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) states that in 2018, Indian workers made up almost 74% of the visa recipients, Chinese workers made up 11% and workers from Canada and South Korea each made up 1%. Additionally, roughly 75% of the visa holders are male.

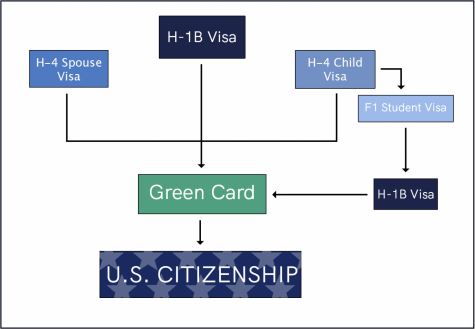

Many H-1B workers come to the U.S. with the intention of becoming permanent residents and eventually citizens. Hence, many workers also bring their spouses and children, meaning their family members also rely on their visa to stay in the country. These dependent family members, defined as children under the age of 21 and spouses, receive H-4 visas, which allow temporary lawful residency in the U.S.. As the majority of H-1B visa holders are male, females make up approximately 90% of H-4 spouses.

Applying for permanent residency

Many American visas are only offered to visitors who do not intend to live in the country permanently. However, the H-1B visa is classified as a dual-intent visa, allowing visa holders to lawfully be present in the U.S. and remain eligible to apply for a green card or permanent residency status. Depending on the visa holder’s circumstances, there are several ways they can apply for a green card. Most H-1B applicants use the employment-based option, in which their employers apply for their green card. If H-1B visa holders have dependents on the H-4 visa, the family members’ green card applications are processed along with the employment-based green card application. Other H-1B and H-4 visa holders apply through the family-based option, but this only offers

permanent residency to individuals with immediate family members who are already U.S. citizens. Of the millions of green card applicants each year, according to the USCIS, 50,000 are given permanent residency status through a random lottery selection, regardless of how they applied.

“America has long been a country that allows people from outside because everybody’s an immigrant,” Pandey said. “America is the number one choice for immigrants from all over the world, so a green card is the most alluring thing for any immigrant. The green card is a status symbol.”

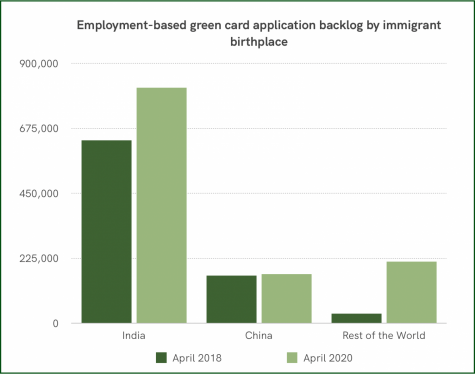

However, obtaining permanent residency is significantly harder than obtaining an H-1B or H-4 visa. As of December 2020, there are a record 1.2 million people in the employment-based green card waiting list. This is due to a per country cap: only 140,000 emigrants from a particular country may receive a green card annually, and no single country can have its emigrants receive more than 7% of the total green cards issued each year.

The evolution and effects of immigration quotas in America

These quotas are nothing new for American immigration policy. The National Origins Formula, which dictated U.S. immigration quotas from 1921 to 1965, began the trend of per-country caps by limiting the total number of immigrants per country and instituting low quotas for immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe in order to maintain the existing ethnic composition of America.

Like the National Origins Formula, the green card program does not consider the population of green card applicants from each country when assigning quotas. As a result, immigrants from countries with high numbers of green card applicants are disadvantaged and prone to long wait times. According to David J. Bier, researcher at the CATO Institute, if everyone on the green card waiting list stayed on it forever, Indian applicants would have to wait an average of 84 years to receive a green card, Chinese applicants would have to wait an average of 11 years and applicants from other countries would only have to wait about 5 years.

“While the national conversation around equal protection and equal treatment under the law is going on around the country, there is still discrimination allowed under the immigration laws,” said Brent Renison, an immigration attorney specializing in H-1B and H-4 visa-related issues. “The Constitution should apply to people no matter the issue of immigration.”

The uncertainty that is associated with the lengthy green card wait times affect H-1B and H-4 visa holders in numerous ways. Until they obtain permanent residency status, H-1B visa holders are required to renew their visas every three years, and if their employer rejects the renewal application—usually due to corporate or legal issues—they can be left without a visa and a job. Thus, H-1B visa holders face not only job insecurity, but also the risk of deportation. If their renewal application is rejected, former visa holders are forced to leave the U.S. within 60 days of their last day of employment.

“The real face of America is that there is injustice in the system, or there are maybe random possibilities that make some people more lucky,” Lee said. “But there is no social safety system that helps people who are not fortunate enough.”

Socioeconomic and familial challenges brought by long green card wait times

H-4 dependent spouses, usually women, face their own challenges. Until February 2015, spouses were prohibited from being employed while residing in the U.S. When the law was changed, spouses could apply for a separate Employment Authorization Document (EAD); however, the process of receiving an EAD is complex and involves multiple levels of legal and personal paperwork. Thus, many H-1B and H-4 families are forced to live off a single income. Having a single income and the uncertainty around residency status can create barriers for families looking to establish their residency and identity in the U.S. by owning property, cars and other investments as they begin to settle down.

“My parents think about buying property, but they’re unsure about their status in this country, so they have to limit themselves as investors and as people expanding their forms of revenue and the ways they can put food on the table,” said H-4 visa holder Aryan Dwivedi, whose parents are on H-1B visas. “Whenever they think of making the same decisions as some of our friends, they have to second-guess because they don’t know if they’ll be here in four years, which is really frustrating.”

The unique struggles of “legal dreamers”

Child dependents of H-1B holders like Dwivedi are known as “legal dreamers.” They are faced with the danger of deportation if they do not receive a green card by the age of 21, as H-4 visas only apply to children under 21. Currently, there are about 100,000 children in the green card backlog who are at risk of being separated from their families at the age of 21.

“[The possibility of living outside the U.S.] is something I’ve come to grips with, because nobody knows what the future holds,” Dwivedi said. “I understand that [moving away] will be a huge cultural shock so it’s a huge mix of emotions, but I am open to it.”

These “legal dreamers,” many of whom immigrate to the U.S. at a very young age, expect to face obstacles in pursuing higher education and employment opportunities. They often feel compelled to consider certain career paths such as business, STEM and law over others due to a greater likelihood of receiving permanent residency status and stability through employment in those fields.

A common short-term solution is the acquisition of an international student visa, or F1 visa, to continue studying in the U.S. for college. However, when students lose their dependency on their parents’ H-1B visas—either by turning 21 or by getting a replacement visa—they are no longer eligible for the combined family employment-based green card application. After college, they not only have to apply for an H-1B visa to work in the U.S., but also must reapply for a green card if they wish to become permanent residents, joining the already overcrowded waitlist.

“All immigrant families have a different situation,” Lee said. “Even if we are H1-B dependent and may be better-off than other immigrants documents-wise, as a student pursuing education, I still have limited opportunities.

Potential legal and political solutions

On Dec. 2, the Senate passed the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act with unanimous approval. (Source: Jonathan Ernst/Reuters)In the past few years, efforts have been made to reduce the green card backlog and relieve H-1B and H-4 families of the uncertainty that comes with applying for a green card. The most notable is the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act, known as S.386 in the Senate and H.R.1044 in the House of Representatives. This act, introduced in February 2019 by Sen. Mike Lee and Rep. Zoe Lofgren, will remove the country caps for employment-based visa holders to receive a green card, and, after a three-year transition period, assign green cards on a first-come-first-served basis.

However, opponents of the act argue that the U.S. should strengthen H-1B and green card applicant requirements, as H-1B visas can be abused. According to the definition provided by the USCIS, H-1B abuse can include H-1B workers not fulfilling duties specified in their H-1B petition and employers favoring H-1B workers over American workers due to personal connections or self-interest.

After negotiations with the opposition, the Senate passed S.386 with unanimous approval on Dec. 2, adding several amendments such as an 11-year transition period. Additionally, the bill now prevents H-1B and H-4 visa holders from receiving more than 70% of the employment-based green cards issued in the next nine years and 50% of those issued in the subsequent years. After being amended, the act must pass another vote in the House before it can be implemented.

Visa holders are also hopeful that the policies surrounding the H-1B and H-4 visa programs will improve under President-elect Joe Biden’s administration and that the process of obtaining permanent residency will become easier. However, many acknowledge that immigration policies may be low priorities for politicians at the moment due to the pandemic and resulting economic crisis. Most of all, many H-1B and H-4 visa holders implore those in Washington to dedicate more attention to visa and residency policies.

“Visa holders are immensely-skilled individuals who pay really high taxes, so I think it’s a community that needs to be kept in this country,” Dwivedi said. “I think we deserve a lot more attention than we currently are getting from both politicians and from the companies that are hiring people like our parents. We shouldn’t have to be scared of the USCIS in the future.”