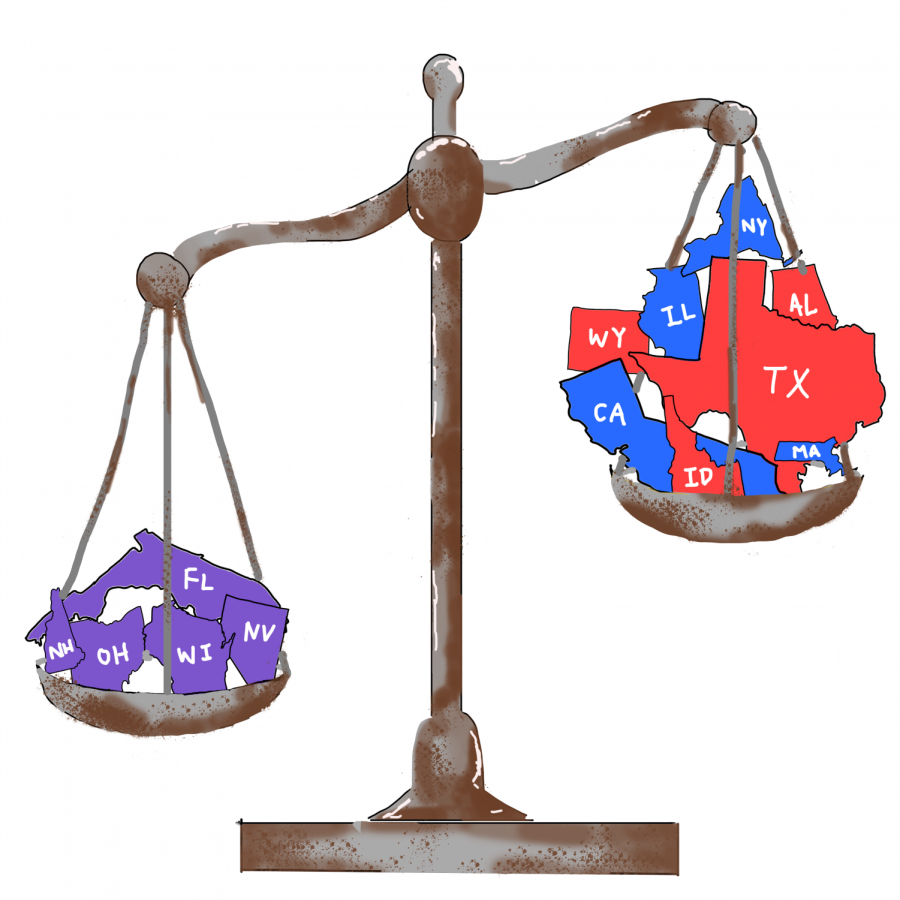

The eroding, expired Electoral College

Graphic illustration by Sharlene Chen

Why should swing states weigh so much more than safe states?

November 4, 2020

The Electoral College needs to go. It’s outdated, wastes votes, lowers turnout, gives a select few states complete control over the outcome of the election and does not accurately reflect the will of the entire American people.

The Electoral College is the current system for deciding the President and Vice President of the U.S. It consists of 538 electors that are distributed to each of the fifty states and Washington, D.C., based on the number of representatives and senators each state has. With the exception of Maine and Nebraska, who split their votes among congressional districts, candidates who win the most votes in a state receive all of a state’s electoral votes. To win the election, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of electoral votes, currently at 270 of the 538 electoral votes.

To understand why the Electoral College is failing, it is crucial to look back at its formative years. When the Founding Fathers wrote the Constitution in the summer of 1787, they created an executive branch whose head, the president, would be decided by a body of elite and knowledgeable voters. In the essay Federalist No. 10, James Madison warned that a direct democracy would give unchecked power to a demagogue and would render the nation turbulent and unstable. Thus the Electoral College was born.

“They were concerned that the average citizen would not be informed enough to make the right choice, or would be consumed by the passions of the day,” said AP U.S. Government and Politics teacher Mike Williams.

Unfortunately, the Founding Fathers could not foresee that the original intent to let the educated elite decide who becomes president would quickly become obsolete due to the development of the two-party system.

“What [the Founding Fathers] didn’t expect was the emergence of a national party structure around two major parties,” Lonna Atkeson, University of New Mexico political science professor, said. “Instead, they expected many localized state or regional parties.”

With increased partisanship in American politics and the leeway given to states over the delegation of their Electoral College votes, many states began adopting the “winner-take-all” system seen today, in which the candidate who wins the most votes in a state — not even more than 50% of votes sometimes — wins all of the state’s Electoral College votes.

“States, not too long into the country, started realizing that they would have more power if they assigned all of their electors to the winner of their state, [since] their state would have a bigger impact,” said John Fortier, Director of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Democracy Project. “So essentially all the states did [this].”

With the adoption of winner-take-all, the function of the actual electors in the Electoral College has become largely ceremonial. They no longer serve as a qualified body in deciding the presidency. Indeed, populist candidates such as Andrew Jackson, whom the elite opposed, have won under the Electoral College. Winner-take-all has further prevented electors from making active decisions. But if it now completely fails to carry out its original purpose, does the electoral system at least fulfill a new role: reflecting the will of the American people?

Absolutely not.

The main culprits in this flawed system are the swing states, which tend to flip-flop between the two parties from election to election. The actual states that are considered liable to swing usually change over long periods of time, generally due to demographic shifts, but in the short term, some states consistently remain swing states while others remain solidly blue or red across many elections. Due to the winner-take-all nature of the Electoral College, it is pointless to campaign in a safe state, since it doesn’t matter what margin a state is won by. As a result, presidential campaigns devote most, if not all, of their time campaigning to these swing states, and the safe states are neglected. In fact, during Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, he visited Florida, a swing state, 21 times for rallies while traveling to California, a safe blue state, only once and never visited Wyoming, a safe red state.

“[The Electoral College] is unrepresentative,” Rachael Cobb, Associate Professor and Chair of Political Science and Legal Studies at Suffolk University, said. “And it’s very unnecessarily complicated. The way that it works right [now] is that states essentially become either important or not important, depending on their status.”

In California, votes from big cities such as Los Angeles and San Francisco contribute to its solid blue status, though the Central Valley, an area with a population of six million people, consistently votes red. Under the winner-take-all system, the Central Valley’s voice is essentially nonexistent. Campaign promises also tend to target issues relevant to swing states, ignoring the concerns of voters of any party who live in safe states.

“In California, wildfires are a particularly important issue [and] water is a particularly important issue,” said Isaac Hale, professor of political science at the University of California, Davis. “Well, it turns out you’re going to hear a lot less about those issues from the presidential candidates than you will about fracking and natural gas, which are issues that matter a lot in a state like Pennsylvania, a swing state. Now, there are a lot more people living in California. It seems reasonable to expect that we would talk about wildfires.”

Voters feel discouraged by the lack of attention in their state and often give up on voting. In the 2016 election, 12 of the 15 swing states had a voter turnout rate greater than national rate, at 58.4% of eligible voters, according to NPR. This disparity is especially evident in the case of Vermont and New Hampshire, states right next to each other. New Hampshire has much higher voter turnout due to its status as a swing state despite the fact it has far stricter voting registration laws.

“Looking at the Electoral College, states that are competitive receive a lot of campaign visits and get a lot of ad spending have higher levels of turnout,” Hale said.

Voter turnout is an essential metric for gauging the health of a democracy. The U.S. already has one of the lowest voter turnouts compared to other developed nations, and its electoral system only worsens the problem. A low voter turnout means that the results of the elections do not accurately express the views of people across the entire country — in other words, the Electoral College silences voices.

So why go through this complicated and ineffective process? In the two centuries since America was founded, has no one proposed a better way of electing the most important leader in the nation?

It’s not that alternatives don’t exist — they do. Previously, the best method to change this system was to amend the Constitution. But in order to amend the Constitution, a two-thirds majority is required in both the House and the Senate, especially difficult with the current state of partisan division. Ratification by state conventions and state legislatures is similarly difficult.

States have been trying something new: the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. This circumvents the need to amend the Constitution by using the states’ authority to allocate their Electoral College votes however they wish to. By signing the compact, the states agree to give all their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the national popular vote, in the event that the total number of electoral votes of the states who have signed the compact exceeds the absolute majority of electoral votes, currently at 270. If an absolute majority of electoral votes is guaranteed to go to the candidate who wins the national popular vote, then the Electoral College effectively has no power.

Currently, the compact has only been enacted by Democrat-controlled states such as California, because the Electoral College currently seems to favor Republican candidates. Two Republican presidential candidates in the last five elections have won the Electoral College while losing the popular vote. Because every state gets a minimum of three electoral votes regardless of population, the system gives more weight to less populous rural states, which generally lean Republican. Though these rural red states have few electoral votes, it does all add up in the final vote count. Additionally, margins in populous safe blue states like California are completely erased, because under winner-take-all, winning California by one point is the same as winning California by, say, 36 points. However, the majority of the presidents who won despite losing the popular vote were not representative of the people’s opinion. Most only served one term, a possible sign of instability, since stability of a presidency is typically demonstrated by the election of a second term.

“You could argue that it makes sense that someone who won by just winning the Electoral College and not winning the national popular vote does not have a very strong victory their first time, they certainly weren’t a huge choice of the people and therefore they might not be as likely to be reelected,” Fortier said. “But again, it’s a pretty small sample so I don’t want to project too much, but all those Presidents have [not been reelected], except for Bush.”

It will also be difficult to pass the compact in swing states, because they would have to give up their power as deciding states in the election.

One argument against the popular vote is that election by popular vote would favor people living in urban areas and ignore the voices of everyone else. However, since many people are concentrated in large cities, their opinions and issues should matter more. But currently, under the Electoral College, swing states maintain more power than they should and campaigns tend to only target problems those living in swing states care about, while completely ignoring the concerns of city-dwellers who live in safe states. It’s important to remember cities are not hive minds either; different people living in the same place can have very different beliefs. In the grand scheme of American democracy, it’s the people and their individual opinions that matters, not where they live.

Another proposed alternative is having states give Electoral College votes that are proportional to the number of votes a candidate won in a state. While in theory, this seems plausible, a reflection of the proportion of the total number of votes in a state would be inaccurate for states with a low number of electoral votes. For example, in a state like Wyoming, which only has three electoral votes, how would the electoral votes be divided if the number of actual votes was split 51% to 49%? Electoral votes cannot possibly be accurately proportionally delegated. Proportional votes by state also do not solve the unfairly disproportionate representation depending on geographical location, since states like Texas have much, much larger populations compared to Wyoming, whose population does not even reach one million. In Wyoming, one electoral vote represents less than 200,000 individual voters, while in Texas, one electoral vote represents roughly 763,000 voters. Furthermore, to implement it, all 50 states would have to agree to allocate their votes proportionally, which is extremely unlikely.

The national popular vote is the most viable solution to America’s broken electoral system. The Electoral College misrepresents the needs of the country, favors voters based on geographical location, discourages voter turnout and skews election results against people who vote for a candidate that best matches their priorities. With its obsolete practices and flawed representation, the Electoral College is truly a failure for choosing the President in this modern age.