Young voters: How voices go unheard in politics

Graphic illustration by Elena Williams

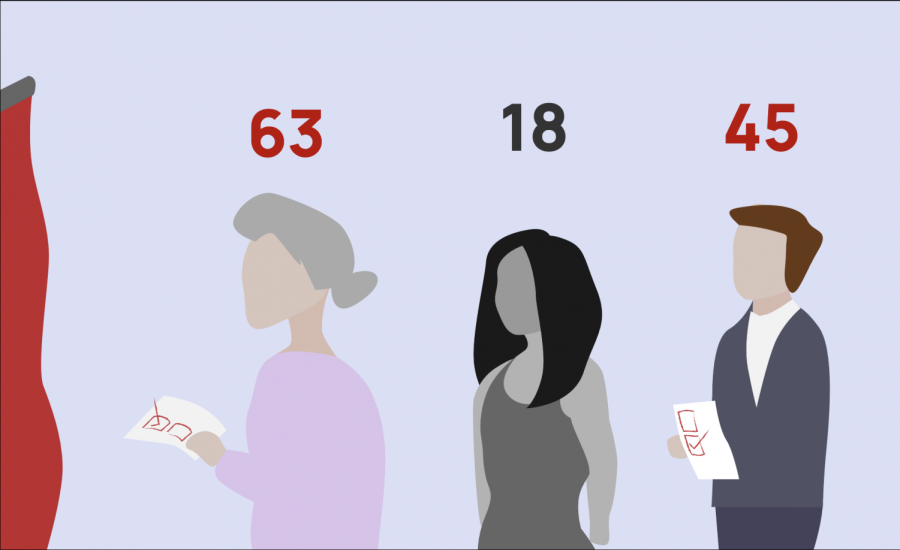

Despite strong political opinions, young voters are often missing from voting lines.

October 7, 2020

It’s not that they’re not opinionated — they are — and it’s not because they refuse to engage — they do. So why is it that young voters, an increasingly distinct coalition, suffer from disappointing turnouts election after election?

From the 1960 election onward, average voter turnouts for America’s primary elections have stayed generally within the range of 50 to 60 percent. However, eligible voters ages 18 to 29 show a much lower turnout at around 30 percent. One of the greatest challenges this demographic faces is a lack of empowerment, the troubling mindset of not being able to make a difference politically.

“[Young voters] feel that their own contribution is not worthwhile,” AP U.S. Government and Politics teacher Jeffrey Bale said. “Some people don’t vote because they think the system is not working for them. And some people don’t vote because they think that they’re not important enough in the process.”

Addressing this issue is the best solution to getting more young people to vote. The idea that young people are apathetic does have its truth, but their apathy stems from the feeling that being involved won’t matter. Whether it is the Democratic or Republican party that ultimately gets elected, the consequence of the election does not seem as significant to youth, who may be more concerned with their education or family responsibilities.

“A lot of times [the solution] is connecting somebody with the issues that matter most to them, and showing them that they can have an impact, because people want to know that they are relevant and that they matter,” Bale said. “When you sell those two things, people are much more likely to join in the process, no doubt about it.”

Restrictive voting regulations in place on the local level have also affected young Americans. Only 24 states allow college-issued student IDs as acceptable forms of identification during in-person voting. Otherwise, students need to present their U.S. passport, driver’s license or other identification, which varies by state. Many voters in this age range do not have a driver’s license yet and may not have a passport on hand. According to CIRCLE, 20 percent of all young Americans who did not vote cited that they had problems during registration or their identification.

In the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder case, the Supreme Court struck down Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). Section 4 of the VRA suspended use of voter tests and Section 5 posited that for districts which used the now-prohibited voting tests and had less than 50 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot in 1964, any further changes to their election laws required approval by the federal government. These determinants were put in place for districts that seemed to have traces of voter suppression. Voter tests precluded illiterate citizens from voting and a low voter turnout suggested marginalization of minority groups. The purpose of the VRA was to allow greater access to voting for any person, regardless of race.

Its implementations were effective, increasing voter turnout by 4 to 8 percent, and minority voter turnout by around 30 percent. After the Supreme Court rendered Section 4, and in turn, much of Section 5’s purpose ineffective, Texas, Alabama, North Carolina and Mississippi implemented new photo ID laws, and research has shown that millions of previously eligible voters were removed from the voter rolls. Many of these include people who are minorities, disabled, young or have low income. In 2018, Georgia saw a purge of voters, 70 percent of which were Black, and New Hampshire has passed a law such that anyone owning a vehicle in-state must also register their vehicle to vote, while those who use a car to drive-in to vote must have a state license.

New Hampshire’s new requirements potentially include hundreds of dollars in registration costs, which could dissuade some out-of-state students from voting. As the youngest Americans are also the most racially diverse, the additional disproportionate effects on racial minorities ripple out to affect young voter turnout as well.

A report by Democracy Diverted found over 1600 closings of polling locations in districts that were once covered by Section 4 of the VRA. This may especially affect young, non-collegiate students, who are shown to potentially face troubles in arranging transportation or inconvenient voting hours and polling locations. Other measures, such as the Texas governor Greg Abbott’s recent decision to allow only one ballot drop-off location per county regardless of size — with some counties’ populations in the millions — are also expected to disproportionately affect young voters as they tend to live more in urban areas. The governor has been accused of voter suppression for this measure.

One of the reasons such focus is drawn to young voters is that they have a unique political identity. Democratic and progressive figures have become increasingly more attractive to young voters. From 2004 to 2017, the number of Democratic-leaning millennials increased by 6 percent, and in 2017, there was a 27-percent difference between the millennial population of Democratic-leaning and Republican-leaning individuals. Without millennials’ votes, the Democratic party, in particular, is losing a large percentage of its voters, and the voices of the younger generations do not reach the government.

The rise of the modern progressive movement came in part from the development of technology, and in particular, social media, which became a platform for targeted campaigns and public discourse largely involving younger millennials and Gen Z. Many political ideologies can be found represented on social media; however, what remains constant is young users’ abilities to learn about politics through social networking platforms.

The Youth Participatory Politics Survey examined the relationship between social media and youth involvement in politics, and the results show that teens and young adults who are involved in online communities, even communities which are nonpolitical, are more likely to be politically involved in later years. The data suggests that social media is being used as a platform for political discussions, which are influencing the younger generations.

“We get a lot of information from social media,” said Ibraheem Qureshi, Gender and Sexuality Alliance (GSA) co-president. “If we see a news article we think is interesting, we’re not going to keep it to ourselves. We’ll post on our story and share it in our groups. We’re talking to each about issues. We’re sharing information with each other.”

Progressive and liberal youth are also being spurred into action in light of cases of social injustice, such as George Floyd’s death. In fact, Floyd’s death sparked protests all around the country and led to greater political interest among youth. Rock the Vote, an organization seeking to help young voters to register for the election, saw almost 50,000 more registrations in the week following Floyd’s death than any other week of 2020. While these voters do not represent all of the views held by their generation, this widespread support underscores the possible effects of more young voices in politics.

“[If young voters increased participation], there would definitely be a shift in politics toward issues that would affect this generation,” Qureshi said. “Climate change would be taken much more seriously. Police reform would go through, as well as electoral reform. There would be less status quo and a lot more radical and more populist ideas.”

Luckily, the number of youth who feel empowered is on an upward trend. As shown by data from the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning & Engagement (CIRCLE), 84 percent of youth ages 18 to 24 feel they can make a difference, which is an 11 percent increase from the CIRCLE’s poll after the 2018 election. Some cities in the U.S. allow citizens as young as 16 to vote in local elections, giving teenagers experience in voting and politics before they become adults.

Early engagement in local politics can pull young voters into political involvement with particular strength, as many feel that their vote has more of an impact on city, county and state-level decisions. Class of 2020 alumna and former Intersections president Sarah Sotoudeh turned 18 before March and was able to vote in the primary elections.

“I think a lot of people, myself included, have underestimated and undervalued local politics [in the past],” Sotoudeh said. “Everyone’s focused on who the president is going to be. While that’s obviously important, what I’d argue is equally important for residents is who their mayor is going to be, who their council members are going to be, who their state legislature is made up of.”

Some believe that the ideas supported by today’s youth may become the standards for tomorrow. Students and the youth have led powerful movements in the past, leading to the reconsideration of now outdated laws and standards. For instance, opposition to the Vietnam War from youth in the 60s and 70s led to protests, particularly at university campuses, that effectively spread antiwar sentiment during the period. Coupled with the civil rights movement, the successful youth-led movements depicted the impact that young people could make in the political sphere.

This era, in which young voices were pivotal in guiding policy, was also a time when they began demanding greater electoral representation. Then, the minimum age to vote was 21. Young adults took up the slogan, “old enough to fight, old enough to vote,” — which led to the passage of the 26th Amendment, lowering the voting age to 18, the same age at which young adults could fight for the armed forces.

The 1972 election, held just one year after the passing of the amendment, saw a great boom in young voter turnouts at about 50 percent. But this surge of electoral participation did not last; since that election, young voter turnouts have steadily decreased. Along with the aforementioned obstacles, current politics have also been deemed a sensitive topic in school classrooms, leading to less discussions and exchange of opinions.

“There are a couple of different approaches you could take,” Bale said. “Number one is to embrace it. As long as a teacher is fully embracing the politics, [they should] have students embrace their political stances, and be able to share them just like they would in the real world. And the other way, of course, is to not talk about it at all. But I think that not talking [about politics] at all is really doing us a disservice.”

Today, as in the 1970s, the younger generation is spearheading the discussions of important issues such climate change and equality. Movements such as Black Lives Matter and those for LGBTQ+ people are generating traction, especially among youth. For instance, in 2013, 70 percent of millennials supported same-sex marriages, a 19-point increase compared to in 2003. They are consistently seen as the most tolerant demographic, and all other generations had less than 50-percent support for same-sex marriage in 2013.

“A lot of Generation Z believes in LGBT rights,” said GSA co-president Alba Olmo Marchal. “Within the last few years, there has been more talk about LGBT rights than there has been in years. As a generation, I do feel like we are much more accepting and progressive. If more young people were active in politics, more talk about LGBT issues would be seen.”

Though young Americans have the lowest voter turnouts, their political involvement is undeniably and increasingly present. The 2018 midterms prompted a surge of young voters in favor of Democratic candidates. Data from the Census Bureau reveals that there was a 79 percent increase in young voters during the 2018 elections as compared to the 2014 elections. The increase in young voter turnout was one of several contributing factors in the wave of progressive candidates who swept Congress in 2018, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York’s 14th District, who performed much better among younger voters. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, two progressive incumbents, maintained strong support from young voters.

California’s local 17th and 18th districts have a history of electing Democratic candidates, and the state has voted blue consistently for several decades. As such, young voters here will likely not tip the scales in the 2020 presidential election. However, young voters still hold great power in primary elections, local elections within California and in swing states across the country.

If the 2018 elections are indicative of a larger trend in increasing young voter turnout, then their growing share of the voting population will greatly affect the results. The switch to mail-in ballots may also prove beneficial to young voters. A study for Utah’s 2016 election demographics compared previous primary elections, as well as the counties that voted entirely by mail and the counties that had in-person voting, and found that the young voter turnout increased when voting by mail.

To prepare for the presidential elections, many organizations such as Rock the Vote and When We All Vote are gearing up to get young voters on board. They have established services to help smooth out the virtual registration process in response to the pandemic, including guides to Voter ID laws and availability of mail-in voting.

“We’ve got to do a better job of speaking directly to the motivations and unique challenges that young and first-time voters face around voting,” former first lady Michelle Obama said in a press release by When We All Vote. “That’s a big part of the reason why I created When We All Vote — to spark important conversations, share critical resources, and make sure people get registered and get out to vote. It’s up to all of us to encourage and work with the next generation to really change the culture around voting.”

Lynbrook students who wish to vote or are interested in the voting process can pre-register to vote online, speak with their social studies teachers or do their own research into politics. The Class of 2023 and Junior State of America have initiated the Viking Vote, a voter registration drive for students to check if they are able to register to vote and how to do so. More information can be found on California’s online voter registration website. Though young voter turnout has been consistently low compared to turnout for other age groups, young voices have the power to make lasting and unique change.

“With more young voters, our government would look completely different right now,” Sotoudeh said. “I think it’s very important for young voters to realize that even if you feel like your vote doesn’t count, you’re a part of this generation which has the ability to influence and sway elections. I think that should be reason enough to vote.”