Lynbrook celebrates Asian American heritages

May 31, 2019

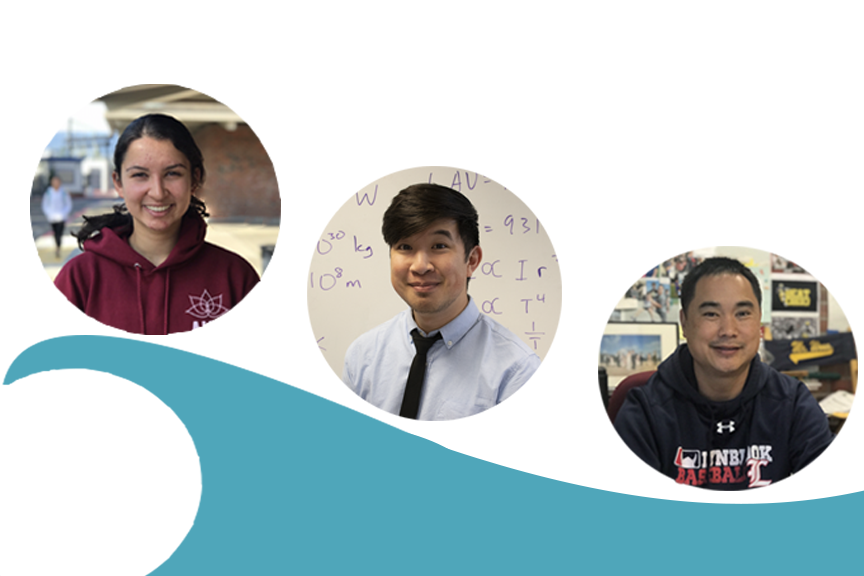

Started in 1978, Asian Pacific American Heritage Month (APAHM) occurs annually every May as a way to celebrate the culture, achievements, contributions and history of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States. Some traditional celebrations include gathering with family and relatives, wearing new and traditional clothes and spending time with others. At Lynbrook, senior Tanvee Joshi, physics teacher Thanh Nguyen and assistant principal Eric Wong celebrate their Asian heritage in unique ways.

Tanvee Joshi

Tanvee Joshi celebrates her North Indian Marathi culture by attending various festivals and parties, such as Diwali, which marks the Hindu New Year, to understand the customs involved.

Between October and November, Joshi celebrates Diwali, a five-day festival which symbolizes the victory of good over evil and knowledge over ignorance. Everyday, her family lights a lamp outside their house and near the images of Indian deities. They decorate their prayer area, the pooja, with artistic designs, wear new clothes and exchange gifts.

“I always love to celebrate Diwali because it reminds me that no matter how far away I am from India, there are still people celebrating its rich culture and others who are appreciating it,” Joshi said. “This makes me very proud of my heritage and my background.”

Diwali, which is celebrated every autumn in the northern hemisphere and every spring in the southern hemisphere as one of the most popular festivals of Hinduism, rejuvenates Joshi’s family with a sense of freshness and increased enthusiasm. Diwali involves the row of clay lamps that Indians light outside their homes to symbolize the inner light that protects individuals from the spiritual darkness.

“Diwali is a time to appreciate the roots that I came from, what I value and what I represent,” Joshi said. “Being a North India Marathi is a huge part of who I am. A lot of my family, friends and events that I take part in are defined by my culture. My culture defines me as a person and shapes me as a being.”

Joshi spends Asian Pacific American Heritage Month taking extra time to appreciate being Marathi and how much her culture has impacted other individuals.

Mr. Nguyen

As a South Vietnamese American, Nguyen commemorates April 30, the Fall of Saigon, also known as Black April. For Vietnamese people, the Fall of Saigon is a day of reflection of South Vietnam’s loss against the communist North Vietnam; on this day in 1975, the North Vietnamese took over South Vietnam capital, Saigon. For older generations of Vietnamese individuals, the day mourns the loss of their homeland, as many were forced to flee their country as refugees.

“For the children, like myself, it’s hard to mourn something that happened before you were even born,” Nguyen said. “When my parents came to America to finish high school, there was a lot of struggle as they were still very young. In the end, they both attended UC Berkeley, where they met, and here I am now. I’m very fortunate to have grown up not having to question my identity. I have my culture as a source of connection to others as opposed to growing up feeling alienated by my identity and my culture.”

Nguyen was raised by his parents and grandparents in America. He attended Vietnamese school every Sunday, where he learned about the language, culture, history and geography of Vietnam. He also had the chance to meet a community of people who celebrated his culture and understood its customs.

“Now that I’m older and I’ve been outside of the Vietnamese bubble, it’s interesting seeing how little remains of my country’s culture outside of the small community that has been created,” Nguyen said. “The South Vietnamese flag that I am familiar with, that I belong to, doesn’t appear in the emojis. South Vietnam’s anthem does not play when the Vietnamese team participates in any international sports. It’s strange to have that disconnect.”

Every year, on April 30, Nguyen wears black to mourn the loss of his people and to remember the tragic history of his ancestors. He wears a yellow tie to represent the flag of South Vietnam, which is a yellow flag with three horizontal red stripes across the center. This year, Nguyen also wore a pin and shoes with patches of the Vietnamese flag.

“My culture, to me, is more of a sense of belonging,” Nguyen said. “There are restaurants and malls and areas of San Jose where I can feel at home. This is where there are a lot of Vietnamese people and where my culture is not only accepted, but also celebrated, as it also connects us all even though we are so many miles away.”

Mr. Wong

After college, Wong moved to Shanghai to work as a teacher for a few years. There, Wong was able to celebrate one of his favorite holidays, Lunar New Year.

“It was absolutely psycho, like the country was on steroids,” Wong said. “I lived in an apartment complex and fireworks were going off. I could not hear the person standing in front of me because the fireworks were so loud. It was like the whole city of 13 million people were setting off fireworks.”

Wong’s grandparents introduced him to Chinese holidays, such as Chinese New Year, where he was given red envelopes, also known as hong bao, and sticky rice cakes, also known as nian gao. In traditional Chinese culture, the red color of the envelopes symbolizes good luck and is thought to ward off evil spirits. Eating nian gao is believed to promote financial prosperity and growth for the upcoming year. During the Lunar New Year, Wong and his family go to San Francisco to dine with relatives. However, since Wong is a fourth-generation Chinese-American whose family is from Hawaii, he is very Americanized; Wong’s father does not speak Chinese, and his grandparents speak fluent English.

“The meaning of culture has evolved over time,” Wong said. “As a kid, I thought of it like ‘whatever I’m Asian, but I want to be a part of all cultures. With my time living in China, seeing my family village, and learning about my dad’s genealogy, my culture becomes more important as I also want to start teaching my kids about it. I try to explain my culture in an appropriate way where they can value it, but also understand that they are living their own lives.”

Having attended college in Michigan, Wong was able to experience a broader variety of cultural backgrounds. At Lynbrook, an Asian-centric environment where almost 85% of the student population is Asian, everything “Asian,” such as having seven boba shops in a one mile radius, seems so familiar to students.

“In other places like Michigan, there are a lot of Asians, but you’re also meeting people who have never interacted with other Asians,” Wong said. “A lot of times with race and culture, it becomes this divisive thing of this is what you do and this is what we do. I always see [race and culture] as a chance to share and educate people because I think that is the biggest way to break down some of the stereotypes out there.”

Read a column from a staffer about how she found her own meaning in her Asian American identity here: https://lhsepic.com/5580/opinion/lost-in-translation-redefining-what-asian-american-means-to-me/.