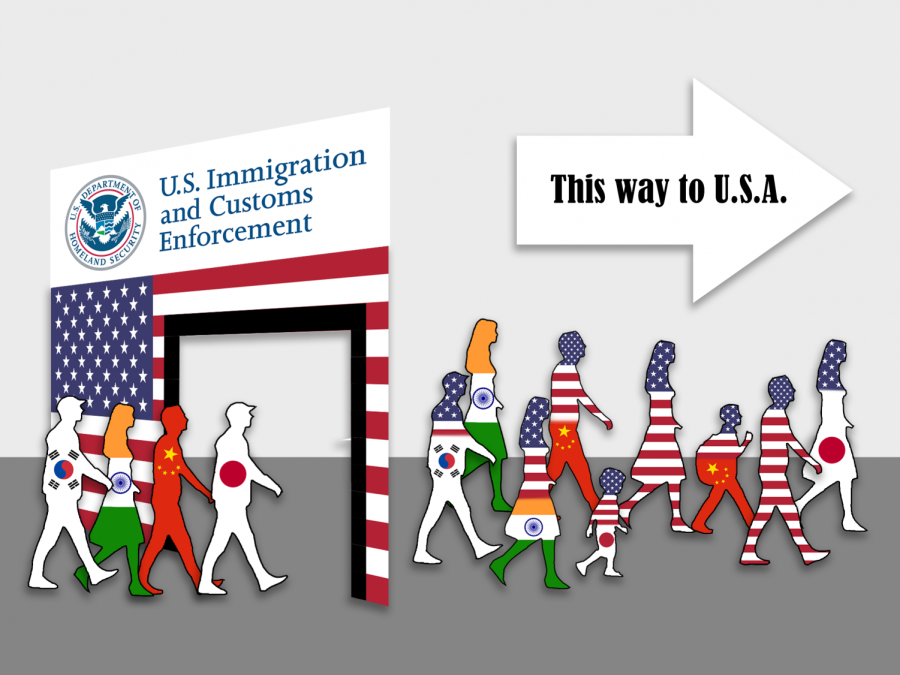

Immigration nation: a mosaic of values

The multicultural identity of second-generation immigrant students

climbing over the cultural wall, beyond the boundaries, how green is the grass on the other side?, to wear a nation and put on the other, how immigration pieces together fragments of cultural identity

March 29, 2019

A century and a half ago, rumors of gold in the uncharted western wilderness of California took the world by storm. Within a span of months, ships began docking in the state’s ports by the hundreds — strange, foreign ships that had never before set path toward the country. They carried silks, spices and sojourners by the thousands, and all at once, the new city of San Francisco became a cultural hub unlike anything the nation had witnessed before. Since then, the influence of immigrants in the Bay Area has increased exponentially. At a school like Lynbrook, whose student body is comprised overwhelmingly of second-generation immigrants, those who live at the crossroads of American norms and foreign traditions harbor a distinct cultural identity.

Since the 1960s, immigration rates have increased drastically. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, first-generation immigrants made up 5 percent of the American population in 1960 and reached about 13 percent in 2010. On the West Coast specifically, first-generation immigrants went from comprising about 9 percent of California’s population in 1960 to about 27 percent in 2010, more than twice the national first-generation immigrant proportion.

In the Bay Area, first-generation immigrants made up about 30 percent of the population in 2010, as reported by the Bay Area Census. The reasons for the particularly high immigrant population in the Bay Area resonate with many in the Lynbrook community: higher education, a better career and a more promising future. Chinese language teacher Freya Li immigrated to the U.S. as a part of an exchange program sponsored by the Chinese government. She completed her undergraduate and graduate studies in Texas with a brief break in between before eventually settling in the Lynbrook area with her husband.

“When I was in China, I had this picture of America in mind,” said Chinese language teacher Freya Li. “I imagined it would be diverse and the food wouldn’t be as tasty as back home. So when I moved to the U.S. in 2014, it was pretty much what I had been expecting.”

Immigrating to the U.S. has had negative results for some first-generation immigrants, such as social or political discrimination as a result of their immigrant status. More than 65 percent of all Hispanics below the age of 30 have said that they have faced unfair treatment on a regular basis as a result of their immigrant identity, according to a Pew Research Center survey. This unfair treatment is applicable to other racial minorities in the country as well.

“Sometimes, people are indifferent to you even though they greet you and say ‘How are you doing?’” Li said. “While these people aren’t hostile, you get the feeling that many of them don’t genuinely care.”

Being a first-generation immigrant is a daunting journey, due to the unfamiliarity with the new country, its citizens, its traditions and everything in between. It becomes even more difficult when one’s family and friends are miles away across borders or continents. Spanish teacher Olga Alonso experienced such a situation when she moved to the U.S. from Spain in 2014.

“I don’t think you immediately realize how hard immigrating is,” Alonso said. “Once you start living here, you notice the differences. The hardest part as a first-generation immigrant is having all my family back in Spain. The distance, the nine-hour time difference. I think it’s very common to feel a bit guilty of not being with your family. Life goes on as it does, but you’re miles away.”

In contrast to their first-generation immigrant parents, second-generation immigrants often find themselves in the unique position of being born as American citizens, but still feeling bound by the norms of their ethnic cultures as a result of their upbringing and social treatment. Some look at this mixture of identities as a complex puzzle, while others feel that this provides for a more enriching experience since it helps them connect better with those they share parts of their identity with.

“At least at Lynbrook, I think that my Asian heritage helps me identify with many of my peers,” said junior Eric Yang. “It’s really cool to share common customs and traditions with your classmates, especially in an environment that never feels culturally hostile.”

However, living as a second-generation immigrant can also pose a myriad of challenges. Such challenges range from racial discrimination to issues of identity conflict. Being brought up in the U.S. instills in second-generation immigrants a sense of aligning more with American cultural values, which can collide with those of their ethnic cultures, leaving them at a crossroads. The clothes second-generation immigrants wear, the music they listen to, the language they primarily speak in — it all becomes confusing when their identity is left in such a complex state. Students like senior Sonali Mbouombouo have adapted to this mixture of identities by embracing and keeping in touch with their ethnic cultures, as well American culture.

“There’s a fine line between my cultural background and American culture,” Mbouombouo said. “I feel like when I was younger, I leaned more toward my German side. Now, the more I’m learning and growing here, the more Americanized I have become. But I still stick to my roots. I have been to Germany to visit my family many times. I still speak German at home, and I never want to give it up.”

Children, whose parents faced many struggles to immigrate to the U.S., often have an internal sense of gratitude. Many parents moved to the Bay Area to create better lives for their children and their family.

“My dad grew up in an impoverished area in Cameroon, so his childhood was much different from mine,” Mbouombouo said. “Same with my mom in Germany. Then, they came here, and I have the life that I have now because of them. I’m always thankful to them for that. They worked so hard to come up to this point, to live in this area and to come out of impoverished beginnings. It amazes me every day.”

Above all, life as a second-generation immigrant is a web of complexities. For some, it can mean engaging oneself in contradictions, from going to school as one person and then coming home as another. It can mean juggling languages by the hour, it can mean feeling alien on one’s own country’s soil, it can mean an extra judging glance at work. It means living as a little bit of here and a little bit of there, a jigsaw of traditions that may never fit together. And for many, living as second-generation immigrants means appreciating this mixture of cultures, values and beliefs as their own distinct intertwined identities, as they embark on their paths to better, and uniquely diverse, futures.