The hunt for affordable housing for Bay Area teachers

November 9, 2018

Amid protests, the San Jose Unified School District (SJUSD) unveiled its proposal to build affordable housing for teachers and other employees at its Sept. 27 board meeting. While some community members are concerned over the plan’s negative impact on home values and taxpayers in the area, the district’s proposal addressed a concern that worries many Bay Area school districts: providing affordable housing for teachers and staff in the increasingly costly Silicon Valley market.

The proposal aims to tackle the housing shortage within the community and retain employees who routinely have long commutes from other cities as a result of this shortage. As the SJUSD came to the point of having to replace one in every seven teachers annually, it began looking toward new ideas on how to address housing concerns. The SJUSD identified nine district-owned properties on which it could build several hundred new units of affordable housing for teachers and other school employees. Some of these properties include schools such as Leland High School and Bret Harte Middle School, which the SJUSD is considering tearing down and relocating in order to renovate the aging school buildings and to make way for housing.

Following news of the proposal, many community members reacted negatively to the idea of building low-income housing in such a prosperous area, as it would lower the value of their homes and tear down the well-established schools. A petition against the SJUSD Board of Trustees, who drafted the plan, received more than 6,000 signatures within a month.

The SJUSD is not alone in its efforts to create affordable housing for teachers. The Los Altos School District Board of Trustees is seeking to set aside $600,000 that could create up to 120 below-market units in Palo Alto that teachers could afford. For this project, the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors have already set aside $6 million, as well as a $3 million contribution from the city of Palo Alto. Housing shortages directly influence school districts as they drive out employees, potentially decreasing the quality of education available at schools by turning off experienced teachers.

The issue of affordable housing is a reality at Lynbrook as well. According to special education teacher Miguel Alderete, in the last decade, Lynbrook teachers have continually been pushed outside the area surrounding Lynbrook as they can no longer afford the rising housing costs.

“When I first got hired here in 2002, there were five or six teachers who lived in the neighborhood,” Alderete said. “Now, I don’t think there are many teachers here in the Lynbrook attendance area, and no one has a house unless they got it through family or they’re married and have dual incomes. Pretty much everyone here now lives outside the community, and some teachers even live in Santa Cruz.”

As prices for housing have continually risen in the years following the 2008 financial crisis, Lynbrook teachers face the dilemma of earning too much to qualify for low-income housing, but too little to afford market-rate rent and home prices in the Lynbrook attendance area.

“Teachers are considered to be in a professional workforce, yet they can’t make enough to live in their own communities,” said Jeffrey Bale, an economics and U.S. government teacher and one of Lynbrook’s Education Association representatives. “That’s detrimental to an extent because anytime that you don’t allow teachers or any members of the community to live within their community, there’s going to be a natural distance that occurs between students and staff.”

For teachers and staff that live far away from the Lynbrook attendance area, long commutes are the immediate result. However, other consequences occur from living in distant cities, such as the detachment between the teachers and the school community.

“My family has intentionally chosen a shorter commute over having a nicer house,” said Japanese teacher Jeremy Kitchen. “If I lived an hour away, I would never bring my children to a sporting event, or stop by a school event. As teachers, when we participate in things outside of our classroom, that contributes to our interactions with students. It impacts our ability to be a community together.”

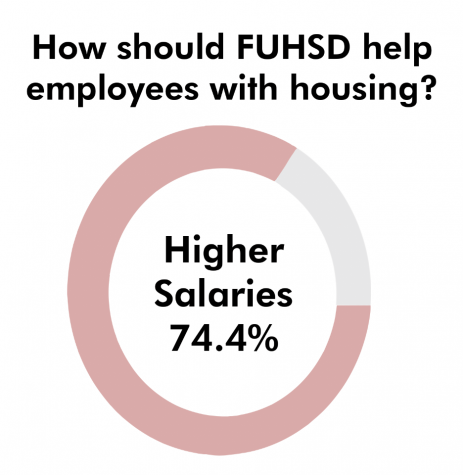

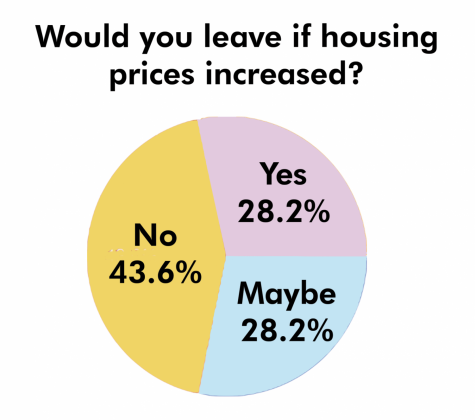

The gravity of the housing situation was reinforced to Assistant Superintendent Tom Avvakumovits when a Monta Vista teacher emailed him: the school had just lost four teachers, three from the English Department alone, all moving out of the area because they could not afford to live in California. Although teacher housing was not a part of his job duties, Avvakumovits helped form a committee of teachers to investigate the issue. Around May 2017, several teachers within the committee created and sent a satisfaction survey to all the staff, including administrators, teachers and support staff. According to the results, more than 60 percent of staff spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing, and of these staff members, 16 percent spend more than half their income on housing. Additionally, 56 percent of staff surveyed said that they would expect to leave the district sometime in the next six years if housing costs are not addressed.

“It’s concerning, and having an education system where people will work for two, three years and then move on to something else doesn’t work for the teaching profession because we want to grow and develop them, as teachers get better over time,” Avvakumovits said. “You want to create a culture, but you can’t do that when you have constant churning. So losing our great teachers would be really troubling.”

Because the FUHSD does not own any additional property on which it can build housing units, unlike the SJUSD, the FUHSD is providing several other ways for staff to access affordable housing; a committee has been put together to explore different options. Included is a program with Landed, a company which aids in potential homeownership specifically for professional workers, such as teachers, who not only seek financial security but also desire to live near the community they serve. Landed covers part of the down payment needed to buy a home, which it estimates to be around 20 percent of a standard mortgage, a form of debt to finance their purchase. In return, the company receives 25 percent of the appreciation when homeowners sell or refinance the house. However, school staff must meet certain criteria to utilize the program: they must be a qualified educator, they must be in need of up to $120,000 in down payment support and have two years of working experience in the district plus an additional two year commitment.

Another option is the Housing Affordability for Teacher Stability (HATS) Program, which builds accessory dwelling units (ADU) or a secondary housing unit on a single-family residential lot owned by another person. Typically, these houses are no smaller than a one-bedroom apartment, and while smaller than the average American house, ADUs can be built for around $160,000 and increase the home value of the property it is built on. However, the program has not gained much momentum as of now because there are many permits required to build an ADU. The FUHSD is currently working with cities to minimize the fees involved with these processes.

The housing situation in the Bay Area is not a situation that can be easily fixed. Though there are proposed solutions, the issue at hand is often too complex for any one answer.

“Solving our affordable housing shortage is like trying to make diamonds less expensive,” said Terel Beppu, a real estate broker in Cupertino. “You either have to dramatically increase the supply of available housing, or you need to significantly decrease demand for it. Increasing supply meaningfully isn’t very likely, as we’ve used up most of the buildable land in the bay area. Mark Twain famously said, ‘But land…they stopped making it.’ He was right. There’s just not much left in the South Bay and up the peninsula. Demand will ebb and flow, but a dramatic decrease in demand for Silicon Valley housing won’t happen unless the area becomes significantly less attractive. There are so many factors that make this an ideal place to live—jobs, food, culture, diversity, weather, access to wine country, beaches, snow skiing in a few hours… If some of the large employers in the area finally decide California is too expensive an area in which to operate and begin relocating out of state, this could quell demand meaningfully. Having said this, when Apple, Google, Facebook, LinkedIn and others are investing billions of dollars in new buildings, it doesn’t appear this will happen anytime soon.”

The housing shortage for teachers in the Bay Area is an issue beyond the control of a single organization, and it affects all people living in the area, whether it be the school districts, school employees or community members. While several other school districts are taking steps to address the concerning situations met by teachers and staff, these measures are still in their beginning stages, as are FUHSD’s own experimental options. For many students, this may seem like a distant issue unrelated to them, but for teachers, this is the reality they must face every day.