Feeling SAD? Blame the weather

Graphic illustration by Vidushi Upadhyay

To create a more accepting community, respecting the needs of people with SAD can go a long way.

May 8, 2023

Many people breathe a sigh of relief when the weather warms up and starts to feel like spring, but it may not bring as much relief to others. Illuminated on social media as “seasonal depression” and formally known as seasonal affective disorder, this condition is related to changes in seasons. Roughly 5% of adults experience SAD for 40% of the year, according to the American Psychiatric Association, while it’s most commonly winter-onset.

The symptoms seen in both types of SAD include losing interest in activities, feeling sluggish, hopeless or worthless and thoughts of suicide. “Winter depression” specifically has symptoms of oversleeping, greater carbohydrate cravings, weight gain and tiredness, whereas “summer depression” may show as insomnia, poor appetite, weight loss, anxiety and increased irritability.

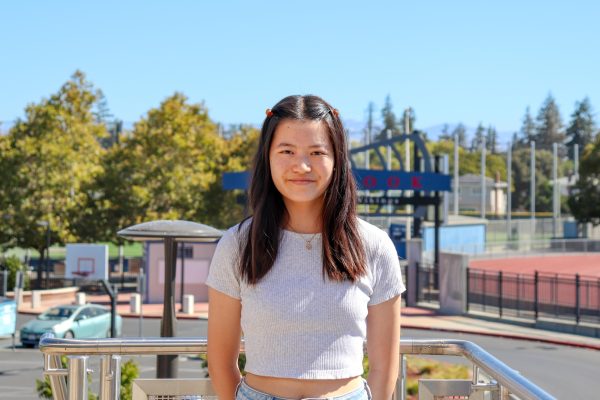

“I once made it to the final round of a contest that involves a pre-scheduled interview, but because of my SAD, I didn’t do anything for an entire week and did not find out until I finally checked my emails,” said sophomore Elizabeth Jiang, who experiences winter-onset SAD. “By then, the day of the interview had already passed. This made me realize my experience isn’t normal.”

The symptoms of SAD generally improve on their own as the season changes but can be rapidly mitigated with a combination of antidepressant medications, communication-based counseling or light therapy. According to the APA, SAD is linked to the lack of sunlight in winter which causes a biochemical imbalance in the brain. Increasing light exposure by just being outdoors or near a window in daylight can improve symptoms.

“Although I have not been formally diagnosed with SAD, I hated the fall because of how progressively dark it would get,” school psychologist Brittany Stevens said. “For 20 years, I had an office at Lynbrook with no window. After we moved into the new GSS building and I got an office with a window, I became happier every single day, probably because I had more exposure to natural light. It’s unbelievable what a difference it makes for me.”

In Stevens’ experience, there is often a stigma around mental health conditions like SAD. Since there is no medical test to identify many mental health conditions, they are sometimes seen as illegitimate or more “self-controllable” than other physiological conditions.

“There’s an expectation that people should just be stronger than a feeling like grief, depression or anxiety — that they should be able to power through that,” Stevens said. “Whether it’s in the brain or another organ, telling someone, ‘don’t be depressed’ or ‘don’t be anxious,’ is just as inaccurate as telling someone to power through any other body dysfunction.”

To create a more accepting community, Jiang expresses that respecting the needs of people with SAD can go a long way.

“It’s not like people with SAD want to be sad when the sky is gray, but the weather influences our mood a lot more than others,” Jiang said. “Just being courteous can really help us feel understood.”