Incorporating patriotism in American education

Graphic illustration by Catherine Zhou

Some believe that the integration of patriotism is at the core of an education that will prepare citizens to join American industries and become active voters.

February 6, 2023

Since its development, the American school system has been continuously reworked to provide all American children a comprehensive education. Some believe that the integration of patriotism is at the core of an education that will prepare citizens to join American industries and become active voters.

Often considered the “father of American education,” Horace Mann standardized and unified school systems, leading the 19th century Common School Movement that ensured basic education for every child. Before this, many children lacked a full education, since schooling centered around the Bible and was largely based on teachers’ preferences. Establishing a secular education standard, Mann developed a varied curriculum that taught children many subjects.

“The general approach to a public education is to provide young people with a broad range of content, knowledge and skills sufficient to launch them into responsible adulthood,” AP Government teacher Mike Williams said.

By 2018, 40 states required students to take U.S. history courses and 28 states required that the course be at least one year long. There are still no national history or government course-related requirements in the U.S.

While history is seen as an objective subject, multiple perspectives and sources used can alter the way students view historical events. As educational laws in the U.S. do not include a standardized, national curriculum, each state develops its own standards for what students should learn.

“If you’re trying to teach World History, you need to talk about interactions between regions at a macro level,” World History teacher Steven Roy said. “If you’re spending all your time talking about Europe or the U.S., that’s neither a comprehensive nor accurate historical narrative.”

Still, while the same topics can be told from multiple perspectives, civics teachers tread the fine line between differing ideologies and morally wrong actions.

“You can see both sides to every issue,” Williams said. “Then, sometimes, societal or government actions can just be plain wrong or illegal. Calling that out isn’t liberal or conservative. It’s calling out what’s wrong or illegal irrespective of ideology. That’s been a challenge for teachers. In American society recently, to some extent, people mix up calling wrong with having a political agenda.”

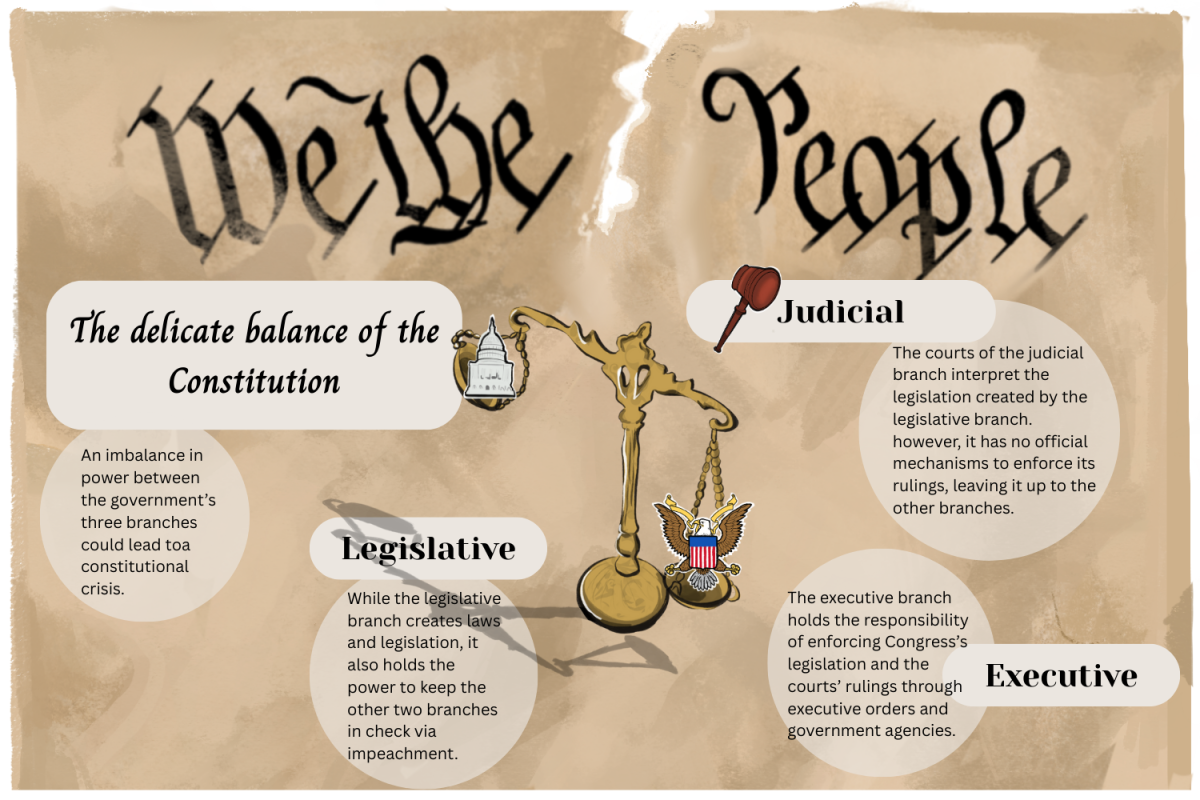

As history continued to be taught in schools, government or civics courses were slowly added. While history courses teach past events, civics courses aim to keep American political traditions alive and allow students to understand the relationships between citizens and the government.

“It’s a degree of socialization that tries to connect us. And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that,” AP Government and Politics teacher Jeff Bale said. “But I certainly believe that, regardless of what students’ personal beliefs are, they should be involved and know the system. The more people whom we have engaged in our democracy, the better and healthier it will be.”

Even though government classes are required in some high schools, there is no way to tell whether students leave class feeling more patriotic or inclined to participate in civics.

“All I can do is present what I can and try to make it as engaging as possible so that the fire will be lit under them and they will want to be involved,” Bale said.

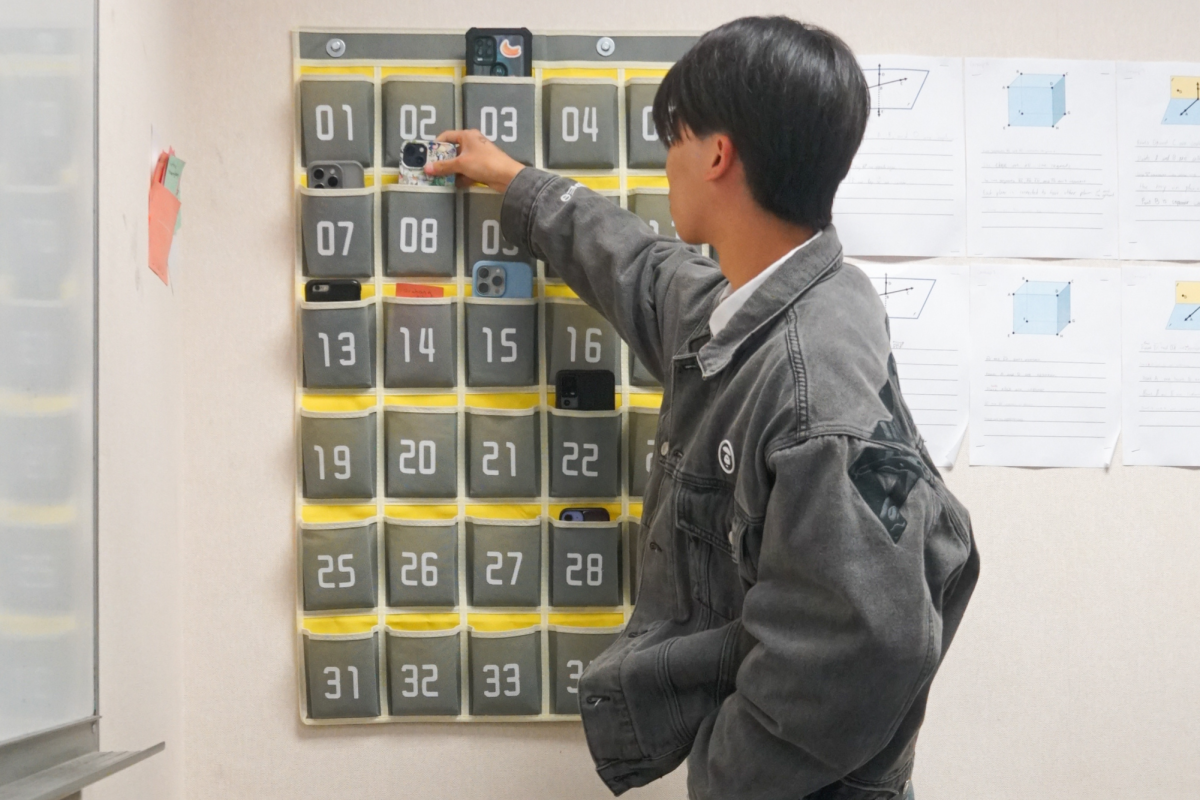

While the Supreme Court has ruled that schools cannot force students to take part in patriotic acts, the government’s promotion of patriotic values is still incorporated into daily school life. The Pledge of Allegiance is required in 46 states, while California education laws require at least one patriotic “act” at school every day. Symbols like a flag salute or the Pledge of Allegiance have remained a staple in the school routine.

“These symbols are respected more than others because they represent foundational American values,” Bale said. “But the values themselves are what really matters, not the symbols.”

As history and civics classes incorporate more perspectives into teaching essential concepts, teachers continue to strive to inform students from an objective point of view.

“When students don’t have a background in a subject, they are unable to question what they are told,” Iziumska said. “The bias in education still influences students, even if schools try to eliminate it.”