The fentanyl crisis: Santa Clara County prompted to take action

Graphic illustrations by Ashley Huang

In an effort to protect teenagers from fentanyl-related deaths, Santa Clara County has supplied many high schools with Narcan kits and provided training for school staff.

December 12, 2022

On Oct. 20, two fathers took the stage at Los Gatos High School. Looking over the worried faces of students and the sympathetic yet fearful expressions of parents in the auditorium, Brennan Mullin and Jan Blom detailed the lives and untimely deaths of their respective children, lost to fentanyl overdoses. In the summer of 2020, each teenager separately took a pill that appeared to be a Percocet but was actually laced with a lethal dosage of fentanyl. In an effort to protect teenagers from similar tragedies, the Santa Clara County Opioid Overdose Prevention Project and the Los Gatos-Saratoga Union High School District co-hosted the event, one of many efforts by Santa Clara County to educate its citizens and mitigate the fentanyl crisis’ toll on the community.

“Data is showing that we’re seeing an increase in fentanyl showing up in communities and society overall all across the United States,” Santa Clara County Office of Education Superintendent Dr. Mary Dewan said. “Part of the increased risk to young people is just the prevalence of fentanyl in our communities.”

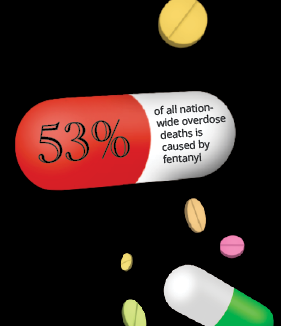

Fentanyl is an extremely potent prescription painkiller, with just two milligrams — equivalent to two grains of sand — being a lethal dosage, according to the National Fentanyl Awareness Day website, a U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency program. It is always risky to consume drugs not prescribed by a doctor or purchased at a pharmacy. In order to cheaply produce controlled substances and increase profit margins, illicit drug manufacturers will often mix the counterfeit powder and pill drugs they produce with less expensive substitutes, such as fentanyl, not taking measures to ensure consumers’ safety. Because these “fentapills” are made to look like their brand-name counterparts, it can be impossible to tell the difference. Once dealers in an area possess the fentanyl-cut counterfeit drugs, they are sold to paying customers, most often through social media and word-of-mouth references in the U.S.

“Fentanyl that is showing up in products not prescribed or sold in pharmacies might be made in a home kitchen or garage, or in a situation where other drugs might be made as well,” Dewan said. “There are no regulations, no standards, no processes. This is incredibly dangerous because even a tiny amount of fentanyl can be deadly, and there is really no way for a person to know if there’s fentanyl in that pill.”

According to the National Fentanyl Awareness Day website, the majority of drugs in the illicit market now contain some amount of fentanyl, with an estimated 250 to 500 million pills containing fentanyl in circulation in the U.S. at any given time, not accounting for powdered substances. A commonly shared sentiment regarding drug use is “don’t use alone,” due to the prevalence of fentanyl and the possibility of it being mixed in the used substance. Drug users may test the safety of a substance by seeing how an experienced friend takes it first. Since the distribution of illicit fentanyl with other drugs is so uneven and unpredictable, the first person to take unregulated drugs could be unharmed and the next could die of an overdose. At least one other sober person should be with someone using to be able to help in an emergency. Signs of opioid overdose include cold or clammy skin, a blue tint to the lips and nails, pinpoint pupils and unstable or loss of breathing and consciousness.

In the event of an opioid overdose, the brain stops signaling the body to breathe, which can result in oxygen deprivation and death. Naloxone, commonly known by its brand name Narcan, is a fast-acting overdose reversal medication that works through either a nasal spray or injection to quickly open the airways, restoring breathing in two to eight minutes. The Santa Clara County Opioid Overdose Prevention Project, an organization aiming to educate and provide resources to youth in the county, offers free Narcan kits and instruction for use at three distribution centers located around the county daily from 1 to 2 p.m. People can also receive a kit and instruction from their local clinic at their convenience.

As of Dec. 2022, SCCOOPP has supplied 40 high schools out of 66 schools in the county with 28 kits of nasal-spray Narcan each and provided training for the school staff. By choosing nasal-spray over injection, SCCOOPP officials hope that anyone will feel ready to administer the life-saving drug in an emergency. At Lynbrook, students can access Narcan at the health clinic in the GSS building. On college campuses, easy access to Narcan kits is being established in the form of vending machines, where students can swipe their student identification to receive free Narcan.

“I tell my patients to keep naloxone handy, and show their family and friends how to use it,” said Stanford Clinical Assistant Professor, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Dr. Huiqiong Deng. “The risk is very low; it can possibly result in opioid withdrawal, but ask anyone who has been revived, they will thank you.”

One of the most widespread ways that the SCCOOPP reaches its target audience of teenagers and young adults is through extensive online marketing. With attention-grabbing slogans like “Fentanyl takes friends,” and “Don’t use alone,” campaigns on social media apps like TikTok and Instagram, along with other means of broadcasting, like radio, have amassed millions of views.

State governments are also rushing to prevent deaths; Senator Dave Cortese, representing Senate District 15, encompassing Santa Clara County, plans to introduce a bill in the 2023-24 legislative session that would prevent fentanyl overdoses through widespread information campaigns, the creation of Behavioral Health Advisory Councils and providing schools with Narcan kits and training on how to mitigate the many effects of fentanyl. Santa Clara County’s pilot Fentanyl Working Group program, as well as the SCCOE, are working in tandem with Cortese to craft the legislation.

At the federal level, Canada and the U.S. have worked together to mitigate the crisis through their Joint Action Plan on Opioids. Both countries have increased funding for Border Security and Law Enforcement to punish street-level dealers and pursue manufacturers. The DEA in tandem with the CDC, other federal agencies and nonprofits have boosted information campaigns, warning the public of the dangers of fentanyl. For instance, the non-profit organization Song for Charlie, which seeks to inform the public about the dangers of fentanyl, partnered with the DEA to recognize the first National Fentanyl Awareness Day on May 9th 2022.

“We need to ensure that any new laws do not imitate drug-war tactics, such as incarcerating individuals who have used them,” Deng said. “Dispensing naloxone and fentanyl testing strips can save lives.”

The opioid crisis as it is known today has three waves. The first wave was when pharmaceutical companies, like Purdue Pharma, overprescribed synthetic opioids such as OxyContin to patients, who inevitably became addicted. At the peak of opioid prescribing in 2012, over 255 million prescriptions for addictive opioids had been written nationwide. The second wave began when state and federal agencies started to clamp down on overprescription which led many to turn to the black market for a substitute: heroin. Drug overdose deaths skyrocketed; according to the CDC, between 2005 and 2016, the age adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths involving heroin went up from 0.7 to 4.9. The third and most recent wave was in 2014, when black markets in the U.S. and Canada were flooded with synthetic fentanyl as dealers saw an increasingly cheap and easy way to roll-back production on heroin. Today, illicit drug manufacturers take to producing fentanyl, even in their own homes, mixing it with other drugs for cheap production.

The pandemic has only exacerbated the crisis with an increase in overdose deaths due to a combination of social isolation, anxiety and a lack of access to health services. The CDC observed that at the height of the pandemic, unprecedented overdose deaths in low-income and minority communities were significantly higher compared to white neighborhoods. Additionally, according to the National Fentanyl Awareness Day website, 86% of youth ages 13-17 report feeling overwhelmed, and 79% report that anxiety and stress are common reasons for self-medication.

The three rules of thumb with drug use in the age of fentanyl are as follows: Don’t source drugs outside of pharmacies or doctors’ prescriptions, never do illicit drugs alone and always carry naloxone; in Santa Clara County, it’s free. Ultimately, everyone can play a role in preventing overdose deaths; from state and federal governments providing a framework for treating and rehabilitation for addicts, to local governments providing educational campaigns and naloxone doses for the public; to individuals educating themselves to learn how to save lives.

“We’re really investing in our school districts and our school communities to make them really focused on wellness and to save lives,” Dewan said. “Ultimately, whatever happens, it is a shared responsibility. It’s the individual, it’s the family, it’s the community, it’s the school and the county. It’s really all of us.”