The laws and ethics surrounding animal testing

May 26, 2022

Behind the makeup that conceals blemishes or the drugs that heal patients, animals are being used to assess the safety and effectiveness of products before human use. The justification of animal testing is an ongoing moral debate between people for and against the use of animals in research.

Humans are the last recipients of products, with the potentially fatal effects of certain chemicals falling on animals. Animal rights advocates argue that there are no cases in which animal testing is justified, yet many researchers deem the testing necessary to assess products for human use.

Many universities and research institutes have organizations to monitor animal treatment in testing. Organizations such as the National Institutes of Health inspect animal facilities to ensure that experiments are carried out according to animal cruelty mandates.

Current federal laws require animal testing on new drugs before they can be used in human clinical trials, which must be done to obtain approval from the Food and Drug Administration for prescription.

In the U.S., the Animal Welfare Act of 1966 is the sole federal law that regulates animal treatment in research, teaching, testing, exhibition and transport. Since the legislation was passed, multiple amendments have been made to improve the act in ways such as raising laboratory animal standards, prohibiting animal fighting and redefining what is considered an animal. Humane organizations often take issue with the fact that the animal must suffer for the testing of a drug which may not work, and ultimately will not even be used on their species, making their lives dispensable.

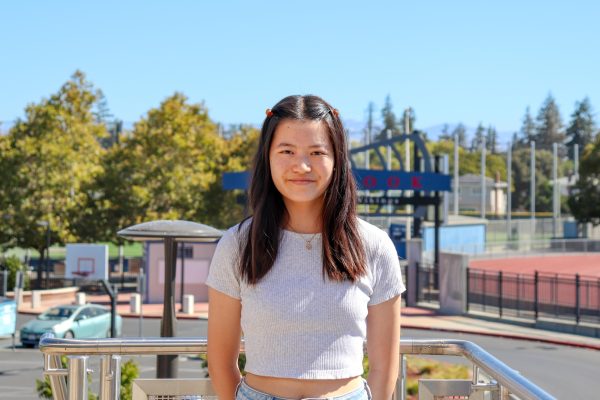

“It’s seen as a form of animal cruelty because it could potentially cost the life of animals, as you first have to give them whatever disease you’re trying to experiment with,” said senior Sophia Wu, co-president of the Health Educational Association club. “And it’s not like the animal just naturally got that disease, so you would be hurting the animal’s life for the benefit of humans and some people don’t really see that as fair.”

A common misconception is that scientists have advanced far enough with alternative testing methods that the use of live animals is obsolete. While alternatives to animal testing exist, such as organoids — cell clusters that approximate living organ tissue and have been grown from a biopsy — and computer modeling, they cannot completely replace animal-based research.

“I think organoids are great, and they can take the place of some animal testing. But again, if you’re developing a drug and you’re going to put it in humans, you probably still need to test it at least somewhat in animals before you would go ahead and start using it in humans,” said Holden Maecker, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Stanford University.

There is also debate over whether animals are accurate simulators of human experience with drugs, given the biological differences between humans and animals, effects of being in a laboratory setting and misalignment in the animal forms of diseases with their human forms.

“Despite the genetic similarity across all mammals, there remain big differences in physiology,” Maecker said. “There’s a lot of things that work well in mice that don’t in humans, because they’re inbred strains with identical genetic backgrounds. As soon as you go into humans or any other outbred species, there’s so much more variation that things may not work as well as they do when you were precisely controlling the genetic background.”

Due to varying beliefs surrounding consumer products developed via animal testing, many brands have included labels on product packaging to indicate whether the product was tested on animals. Labels including the words “cruelty-free” paired with a rabbit symbol, such as the pink bunny from the Coalition for Consumer Information on Cosmetics’ Leaping Bunny Program, is one label that serves as a denial of participation in the animal mistreatment that many believe comes with animal testing. These labels assure those hesitant to use animal-tested products that they are not supporting companies with morally gray methods. However, these labels may not matter anymore if Congress passes the pending Humane Cosmetics Act, a bill introduced in late 2021 prohibiting the use of animal testing in the development or evaluation of cosmetics products, along with its sale and transportation.

However, California is the first state to pass legislation banning animal testing in cosmetics. Governor Jerry Brown signed the California Cruelty-Free Cosmetics Act in 2018, which prohibits the sale of animal-tested cosmetics and went into effect on Jan. 1, 2020.

“I think it would be better if scientists didn’t put animals in harm when they don’t need to, so having legislations that limit that are good things,” said Wu.

Although the well-being of animal test subjects is not always sacrificed in animal testing, the difficulty of weighing whether animals should be subjected to testing for human benefit blurs the ethics of animal-based research in science.

“A lot of people would like to say ‘Don’t do animal testing; it’s bad,’ but a lot of that reputation came from things like the cosmetics industry,” Maecker said. “If you talk about cancer, when people are dying because there aren’t viable treatments, testing drugs on humans first may do more harm than good. There is a place for animal testing, it just has to be well regulated.”