Survival of the fittest

As admissions officers seek to make minute distinctions between equally hard working, promising applicants, they must consider if, and which, students are being provided with the resources to find their fit.

March 8, 2022

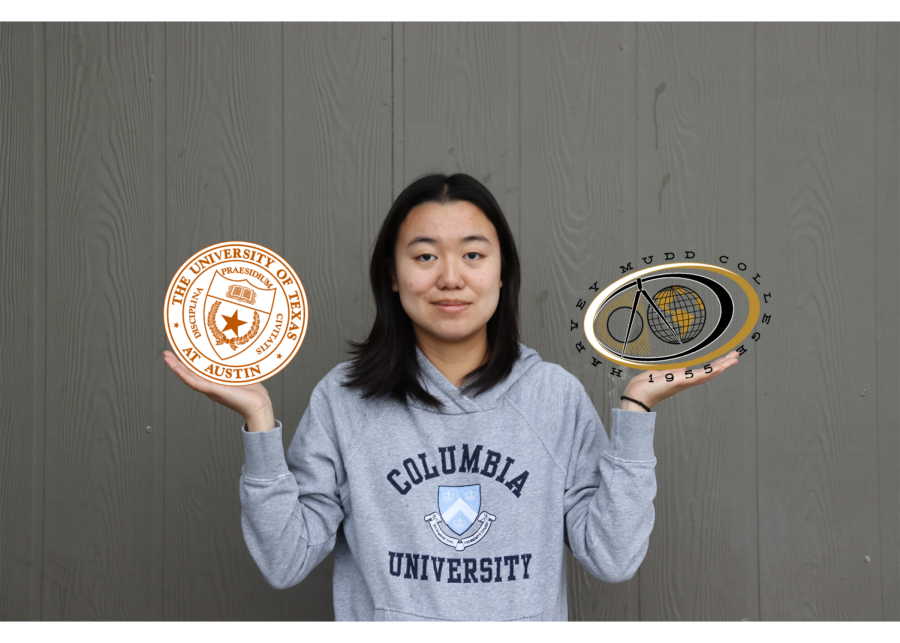

Why did I apply to 25 colleges, in spite of popular advice and appreciation for my sanity? Besides competitive admissions for my major and uncertainty about my strength among the applicant field, I disregarded the College and Career Center’s recommendation of 10 to 15 schools because I didn’t know what I wanted out of a college experience or how I “fit” into a school’s culture. Harvey Mudd, a small liberal arts college, was just as appealing to me as a massive public school like UT Austin.

I shifted my focus to finding the best schools for my major, scouring each school’s website to locate the academic and social hearts of the school, but I couldn’t take the information at face value because at the end of the day, it was all marketing — designed to position each school as a sterile amalgamation of diversity points, interdisciplinary study and world-changing innovation. Though more trustworthy, I didn’t always find my goals or background represented in primary sources like vlogs or subreddits either.

I heard enough second-hand anecdotes to be confident in my understanding of two schools: my sister’s Ivy League school and UCLA, where my friend studies as a freshman. This incredibly skewed vision of college life left me with 23 more schools that were gambles. I had no idea if the impression I cobbled together from promotional materials and websites was enough to secure admission and more importantly, a happy four years on campus if I was admitted.

The obstacles students face when determining their college fit are often much more damning than they were for me, especially for the most vulnerable students, who often lack access to resources to determine fit and see college as a crucial form of social mobility.

The two primary methods of determining college fit are to speak with current students or alumni and to visit campus. However, both presume a degree of privilege. The ability to speak to family, friends or upperclassmen about college assumes that the people around you are going to college, and college visits assume the privilege of having the free time and money to tour the East Coast over the summer to better understand the campuses of the Ivies.

With college applications becoming more competitive, subjective elements in the application process, like fit, become increasingly important. Admissions officers must consider the privilege intertwined with being well-acquainted with the culture of top-20 universities and provide more options for students to get to know their schools. Fly-in programs, air-fare-included preview weekends for low-income or underrepresented applicants, are a great solution, but are currently offered mainly by small liberal arts colleges. The highly selective admissions to these programs defeat their motivation of providing access, and increased investment from the schools that offer them is necessary to expand their scope by allowing more students to determine their fit.

At the end of the day, fit means happy students and a happy campus. But as admissions officers seek to make minute distinctions between equally hard working, promising applicants, they must consider if, and which, students are being provided with the resources to find their fit.