Gaming the rankings: Race to the top

Graphic illustration by Sharlene Chen and Lillian Fu

As college rankings gain popularity as ways for students to weed out the best schools, many colleges have discovered loopholes to climb toward the top.

December 7, 2021

College education has always been synonymous with social mobility. With more than 4,000 accredited higher education institutions in the U.S., finding the right one can seem like finding a needle in a haystack — and that’s where college rankings come in.

Rankings from U.S. News, Forbes and Times Higher Education impact student decisions and higher education institution admissions. As these rankings gain popularity as ways for students to weed out the best schools, many colleges have discovered loopholes to climb toward the top.

According to David Webster, the author of Academic Quality Rankings of American Colleges and Universities, rankings can generally be defined as a list of the best colleges and universities according to the creators’ interpretation. Rankings can be used to compare individual departments within a college or university and measure the quality of an institution holistically; there are separate rankings for graduate education.

College rankings are either based on outcomes or reputations. Outcome-based rankings use data about a student’s post-graduate success — with differing methodologies — to approximate the quality of the education at that school. Reputational rankings are based on peer review and focus on the institution’s reputation over the prominence of graduates.

Between 1910 and the 1960s, the quality of colleges was most frequently judged through their education of distinguished persons. The first outcome-based rankings were published by James Mckeen Cattel, a psychologist who studied eminent men. The first methodology for reputational-based rankings was developed in 1925 by Raymond Hughes, a chemistry professor at Miami University in Ohio. Reputational-based rankings would become the dominant form of academic quality rankings starting in 1959, paving the way for U.S. News’s debut.

U.S. News published its first reputational-based college rankings in 1983. In their first three years, they provided college and university presidents with a list of schools similar to their own and asked each to choose the five schools they felt provided the best undergraduate education.

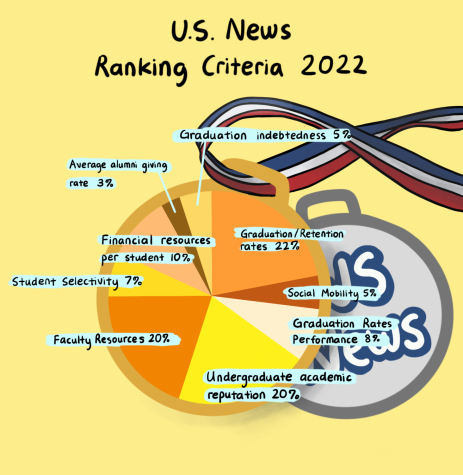

Beginning in 1988, U.S. News started publishing annual rankings and made changes to their methodology after academics criticized the reputation-based rankings. Afterward, U.S. News started to include opinions of school faculty and decreased the reputational component to 25% of the overall ranking, with the remaining 75% for data determined by admissions selectivity, faculty strength, educational resources and graduation rates, similar to the criteria used today. Since then, outlets have constantly tweaked their methodologies to better capture what they feel makes a college great. The popularity of U.S. News rankings led to the creation of other rankings, most notably The Princeton Review in 1992 and Forbes in 2008.

“Rankings became popular through marketing campaigns that cropped up in the 80s hyping rankings as authoritative, and high-ranking schools as more valuable,” founder and CEO of Bluestars Admission Counseling Amy Morgenstern said.

U.S. News splits colleges into four categories: national universities, liberal arts colleges, regional universities and regional colleges. The latter two categories are further split into north, south, midwest and west. Alongside data from annual spring surveys sent to each school, college administrators also report their SAT score average, retention rate, graduation rate and more.

“It is very helpful to have rankings laid out for you that you know are chosen by well-known publications with extensive research,” senior Nishi Kaura said. “It’s more convenient than going and researching each college on your own, as these rankings are suitable for everybody and have made the college application process much easier for me.”

Forbes also publishes annual college rankings based on its own criteria, which rank the top 600 schools in the country. Although long considered a reliable source, Forbes faced major backlash this year when it ranked UC Berkeley at No. 1, ahead of institutions such as Princeton and Stanford.

The reason for UC Berkeley’s sudden leap to the top was Forbes’s change in ranking methodology, as they integrated a new criteria of low-income student outcomes. James Weichert, Academic Affairs Vice President of the Associated Students of UC, believes that the school’s diversity stems from new test-blind application policies, which aim to remove biases in the admissions process.

However, those policies stirred controversy, especially in the Bay Area, where many believe colleges should be ranked purely by academic prestige.

“I think it’s very important that all students, including low-income students, feel like they can thrive at a university,” Kaura said. “But, I don’t think those numbers should be considered above the actual academics and quality of education that a university offers. UC Berkeley is considered a public Ivy, but I don’t think it should be at the top just because of this low-income outcome criteria.”

When colleges are ranked higher, their number of applicants typically increases, which directly affects the amount of funding and tuition they collect.

For many students, these rankings play a substantial role in determining which schools they apply to.

“People really care about brand names and about rankings, and when a student might not be a top 10, top 20 or top 30 student, I tell them to not worry,” Morgenstern said. “I really wish students didn’t feel bad about themselves. So many highly successful adults went to schools we might not consider prestigious. Everyone has their own path.”

The average college graduate earns around $30,000 more than people with a high school degree each year. Considering the academic competition students face at Lynbrook, students also feel pressured to shoot for the most prestigious colleges — even though they may not be the best fit for them.

“Lynbrook culture encourages students to apply to as many schools as possible, and at the end of the day, they all end up being super prestigious schools,” senior Amy Zhou said.

In recent years, with college admissions becoming more competitive, several colleges have been caught gaming the ranking system by finding creative ways to meet ranking criteria and even falsifying admissions data.

For example, beginning in 2005, Claremont McKenna College, a small southern California liberal arts school, inflated each SAT score by 10 to 20 points when reporting them to U.S. News. While seemingly minor, such changes can boost a school by a few spots, which can influence applicants building their college lists and accepted students choosing a school to commit to. With a 10.3% acceptance rate, Claremont McKenna has always been regarded as an excellent college, but its fraudulent activity has propelled it to a prestigious No. 9 in the U.S. News liberal arts colleges ranking.

In 2012, George Washington University in Washington, D.C. was caught falsifying high school class ranks of incoming students, and Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. was caught misreporting high school GPAs of incoming students.

In 2008, Baylor University in Waco, Texas, offered students scholarships to retake standardized tests after they were accepted by the university in an effort to boost SAT and ACT scores on its report to U.S. News.

Another university that has repeatedly made headlines for their manipulation of the ranking system is Northeastern University, located in Boston, Mass. Richard Freeland, who became president of the school in 1996, devised a plan to boost the school from its then No. 162 spot into the top 100 national universities, even calling it a life-or-death matter for Northeastern. Northeastern now holds a rank of No. 49.

In order to reduce class size at Northeastern, he hired additional faculty and made sure most classes had 19 students, just under the 20 student maximum that U.S. News was looking for. In 2003, Northeastern started allowing applicants to apply through the Common Application, driving application numbers up and acceptance rates down. Northeastern was also able to construct new dormitories, which have been proven to increase graduation and retention rates. Freeland and his colleagues even approached other schools’ presidents to influence Northeastern’s peer rankings.

In 2004, Freeland even met with Robert Morse, author of U.S. News rankings, to protest the publication’s approach in grading Northeastern’s co-op program, where students spent the semester gaining career experience instead of taking classes. He won his point, and Northeastern eventually stopped including co-op students in its reports, which made school resources seem better allocated across less students.

“There’s no question that the system invites gaming,” Freeland said in an interview with Boston Magazine in 2014. “We made a systematic effort to influence the outcome.”

Recently, Northeastern admissions employees have also spent resources traveling to recruit as many applicants as possible, making the school appear even more selective.

While rankings are valuable, they are overemphasized. It is ultimately more important for students to find community, grow their passions and establish financial security later in life. Inaccurate college rankings hurt students above all.