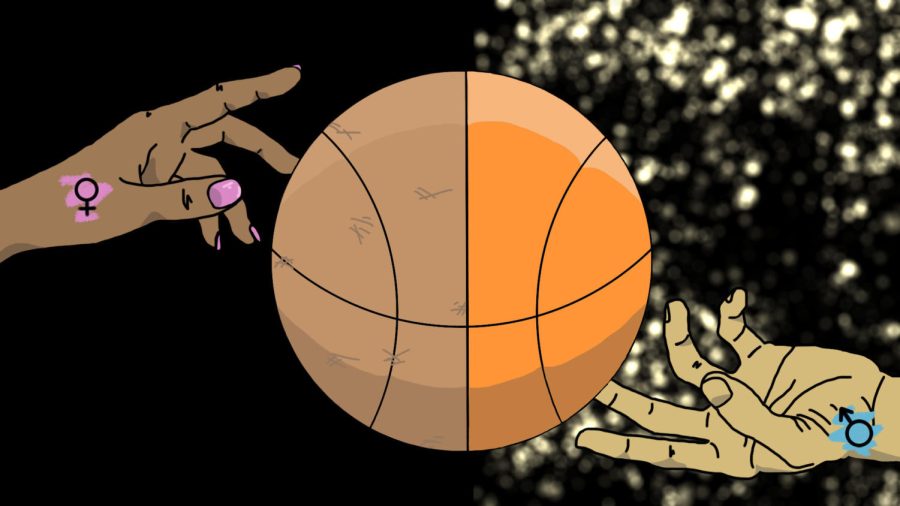

The history of sexism of the NCAA

Graphic illustration by Alara Dasdan

The NCAA invests millions of dollars to ensure promotion, equipment and coverage for their male athletes. However, for their female athletes, it’s a different story.

April 23, 2021

The NCAA has recently come under scrutiny after a video from Sedona Prince, a member of the University of Oregon’s Women’s Basketball team, went viral on Tiktok. The NCAA responded to outraged viewers by slightly improving the quality of women’s equipment in this instance, but it should be more actively securing equality between athletes in every situation. This was not an isolated incident; the NCAA’s history of sexism stretches back for decades. As stated on its page, the NCAA “equips student-athletes to succeed on the playing field, in the classroom and throughout life.” The widespread use of social media has helped expose the falsehood of this statement, but the NCAA must start acting as the non-profit service it claims to be, rather than placing their less profitable divisions at a disadvantage.

Fans of March Madness uncovered multiple discrepancies between the NCAA’s treatment of men’s teams and women’s teams at the tournament. Not only was the women’s weight training equipment laughable compared to the men’s, but the food provided for women was also prepackaged meals, whereas the men received a full buffet, and the women’s “swag bags” — free memorabilia provided for participating athletes — were stocked with far less merchandise.

“I was really appalled when she mentioned that the NCAA claimed that [the weight training equipment] was due to a lack of space, which she then clearly showed was not an issue,” sophomore basketball player Aneesha Jobi said. “She also showed that it was not a fluke, as there were disparities between food, bags, and equipment that men and women received. Somebody knew that the men were getting more than the women, and they just chose not to do anything about it.”

Most concerning of all the differences were the COVID test qualities: daily antigen testing for women versus a far more accurate daily Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) testing for men. Women only had access to PCR tests following positive antigen tests, as the latter were prone to false positives. Shaylee Gonzales, an athlete at the Brigham Young University’s Cougars women’s team, received a false antigen positive and waited for two hours to be retested with the PCR. These inaccurate test results put female athletes’ health at risk, turning the inequality from inconvenient to dangerous, as well as delaying other events such as training.

Stanford coach Tara VanDerveer and Setsuko Ishiyama, the Cardinal’s director of women’s basketball, issued a statement on Twitter in response condemning the NCAA’s lack of concern.

“Seeing men’s health valued at a higher level than that of women, as evidenced by different testing protocols at both tournaments, is disheartening,” VanDerveer and Ishiyama said in the written statement.

The current issues extended beyond the March Madness scandal. For the NCAA’s Division I Women’s Volleyball Championship, athletes and coaches expressed concern over the mediocre accommodations provided for them. Athletes were expected to change with no locker rooms provided, play matches on concrete floors, and court arrangements likened to a high school tournament. The first two rounds were planned to be aired without play-by-play or analysis. The NCAA released a statement in response to these complaints, but the fact that it happened it all is cause for concern.

The NCAA was also sued twice in sexual harassment cases by female athletes in the past year for failing to provide a safe environment, caused by organization’s lack of enforcement in situations of harassment or assault. One such lawsuit called to attention the NCAA’s disbanding of the Commission to Combat Campus Sexual Violence in August 2018. The NCAA responded to some of these cases by requesting a federal judge dismiss them, arguing that it is not legally obligated to create a safe environment for its female athletes. Donald Remy, chief legal officer for the NCAA, released a statement during the cases specifying how “the NCAA is committed to working with its members to combat sexual abuse,” though their lack of action says otherwise. The NCAA and its events hold strong influence over the sports industry; even if it is not required to do so, it should still make more of an effort to combat sexual violence because of this.

Part of the issue stems from the fact that Title IX, the federal law which dictates that an individual cannot be discriminated against on the basis of sex, does not legally apply to the NCAA. In the supreme court case “NCAA v. Smith,” the Supreme Court ruled that, since the NCAA is funded by its member institutions, it need not abide by Title IX. The NCAA has since announced that it voluntarily complies with Title IX code, but these recent scandals have proven otherwise.

“The problem is that I think the NCAA has turned itself into a business more than a service when it should be a service,” cross-country coach Luca Signore said.

Over the years, the NCAA has released ad campaigns, named brand building rooms and created documentaries highlighting the achievements of their female athletes. However, based on recent events and their lack of financial investment in women’s teams, it is evident that these actions are more performative than genuine. The NCAA released a gender equity report spanning from 2004 to 2010 which details the difference in revenue, expenses, pay and participation between male and female athletes. The statistics show that female athletes receive less monetary support than male athletes. For example, the men’s assistant coach median salary increased from $601,500 in 2004 to $1,004,100 in 2010 whereas the women’s only increased from $317,200 to $499,200 — a 66.9% growth versus a 57.4% growth, respectively, and much lower numbers on the women’s side. This is partly due to a broader sexist issue of less interest in women’s sports which leads to lower investment from broadcasting companies, but nonetheless is an issue that deserves addressing. Athletes, coaches and even the NCAA itself have mentioned the gender-based pay gap, but little is being done to solve the issue.

This behavior, particularly from a major sports organization, is unacceptable and harmful. It sets an example for others that will risk the safety and well-being of female athletes and creates a vicious cycle through delayed intervention.

“The impact is really on the younger generation,” Jobi said. “I know like people tend to say that all the little girls seeing this won’t have like a good like role model or they won’t think that they can go into sports, but I feel like the also this could affect younger boys, because this instills the idea in their mind that men’s sports are superior. They grow up with that belief and this cycle just continues.”

Student athletes at Lynbrook have also encountered underfunding. Rachana Aluri, a junior volleyball player, described her experience with it.

“Very often, women’s sports are underfunded and undervalued,” Aluri said. “Underperforming boys teams will usually have really nice equipment and a lot of funding, while the girl’s volleyball team at Lynbrook went undefeated until [Central Coast Section] semifinals and was struggling to find a coach every year I’ve been at Lynbrook. We struggle to find enough jerseys for everyone to wear, and struggle to stretch the broken nets far enough across the poles.”

Over the years, the March Madness tournament revenue has mainly comprised of the men’s matches and the majority of viewership was directed toward the men’s division, most years reaching at least 10 million more viewers than the women’s division. This year, this pattern could still be seen, but the women’s tournaments gained more viewership than it had in years. The women’s Sweet 16 games increased by 66% compared to 2019. While still far lower than the men’s viewership, it could be a start.

“Hopefully, the NCAA can sort of realize that there is money in women’s sports,” Signore said. “Maybe they are realizing they can actually promote women’s sports, and it’ll be financially beneficial for them and beneficial to the athletes.”

If viewers continue to tune into the women’s tournaments, it could create the incentive the NCAA needs to take long-overdue action. Support through social media could hold the organization accountable. In an ideal future, the NCAA would value its athletes regardless of gender, but for the time being, it unfortunately falls upon the viewers to ensure that athletes are treated equally.