Editorial: Policy and practice: Creating a safer culture for sexual harassment survivors

FUHSD recently updated its policies on sexual harassment — what happens next?

December 15, 2020

FUHSD Board members recently passed a measure that amended their sexual harassment policy to be more compliant with Title IX, a federal educational amendment which protects students from discrimination on the basis of sex and guarantees that schools will protect students and staff from sexual harassment. While these new policies are steps in the right direction, district administrators and students need to actively and consciously work together to create a culture where sexual harassment is collectively condemned.

The new amendments were made in response to new California laws passed in 2019. Assembly Bill 34 and Assembly Bill 543, passed on Sept. 12 and Oct. 2 respectively, which called for extensive changes to district guidelines on sexual harassment. These measures included posting the district’s sexual harassment policy on their website, making it easier for sexual harassment complaints to be filed and assigning a Title IX coordinator to each campus. Some of these policies had to be adjusted for distance learning, which delayed the district’s compliance with these new laws.

In addition to these changes, FUHSD is also in the process of implementing several educational modules on sexual harassment throughout the school year. The first module was completed at the beginning of the 2020-2021 school year; in the activity, students had to click through a slideshow that defined sexual harassment and informed students of their rights.

“[FUHSD] thinks that their modules are enough, but you can always do more,” Fremont High School junior Rheyanna Rivera said. “I hope they do [modules] more often, and not just because of the attention it’s getting right now. It should be normalized that simple things like consent, sex education and how to treat someone the right way are taught in our education, be it in public or private school.”

The district invited guest speaker Mike Domitrz from the Center for Respect, a nonprofit organization dedicated to establishing cultures of respect, to teach students the importance of boundaries, bystander intervention and support. The assembly, held on Dec. 9 at Lynbrook, did an admirable job of teaching the basics of asking for consent and intervening when witnessing sexual harassment or assault through easily digestible four-step processes.

“I thought Mike was great,” said Lynbrook sophomore Omar Haq. “He was able to host discussions where the majority of female students were able to feel comfortable speaking about this topic, and was also able to educate the majority of the male students at Lynbrook to understand the gravity of the subject.”

The tone of the assembly was also far more lighthearted and informational when compared to past sexual harassment assemblies, which some found too aggressive. Students also felt the old assemblies also portrayed sexual activity in a negative light, which furthered the stigma around sexual harassment and assault. With the Center for Respect assembly, however, Domitrz was able to establish a safe space for all.

“I felt like the sexual harassment assemblies the school usually does are impersonal and sound accusatory [towards survivors],” Lynbrook junior Divya Singh said. “This year’s assembly was much lighter. Just having someone who was able to take a serious topic and convey it in a way that could be understood was a major improvement from last year.”

The district made the changes to their sexual harassment policy based on statewide recommendations from the California School Board Association (CSBA). FUHSD’s legal team then stepped in to assist district leadership with incorporating those recommendations into an updated board policy. The decision to add modules was taken independent of the CSBA recommendations and was made due to growing student concern about sexual harassment.

“In the summer of 2017, our deputy superintendent, directors of [Human Resources] and I attended a week-long workshop where we received specific training that would assist us in updating our procedures and policies,” Title IX coordinator Trudy Gross said. “After the seminar, we began to consult our legal firm on how to go about incorporating that advice. This summer, we took those templates from the workshop and we updated them based on the School Board Association recommendations while consulting our legal team throughout the process.”

In accordance with these new laws, a mandatory poster will also be hung in every classroom once students begin to return to in person instruction. It will include information about how to report sexual harassment and will let the student know that they have rights supported by the district. Much of the information in the first sexual harassment module is also reiterated on this poster.

While the district has made significant progress in updating its sexual harassment policy to be more accessible and available to all students, there is still work to be done. Further increasing transparency about the investigation process and ensuring the safety of complainants during the investigation process will make the district seem more approachable as a whole.

FUHSD Board Policy 5145.7 (BP 5145.7) states that the superintendent must ensure that information about the district’s procedure for investigating complaints is made public. However, the district has not made this information widely accessible, and can be difficult to find on the district website. This often leaves both survivors and students afraid and confused about how to come forward and report harassment or assault to district administration.

“Quite frankly, I didn’t file a formal report for what happened because I was scared,” Lynbrook Class of 2020 alumna Nicole Ong said. “After talking to other students who are more experienced with reporting this kind of stuff, I know what does happen in a [sexual harassment] investigation. But I didn’t as a high schooler, and even now it’s terrifying. lt felt super scary as a victim, because it’s kind of like, ‘oh there’s an investigation,’ as if your experiences are in question. I was scared that if an investigation happened, the tables would somehow turn and I would be the one in trouble. I’m going to argue that while it’s fairly obvious to [school administration] what an investigation entails, it’s not obvious to any of us.”

As of now, the district’s investigation policy relies heavily on student interviews, as more often than not, there are only two parties that know exactly what happened. The investigation uses the doctrine of “preponderance of evidence,” which states that if any statement made is more likely to be true than not, it should be taken as absolute truth. This requires investigators, which consists of district Title IX officials, to mediate in order to determine the credibility of victims and the accused.

“I would say in terms of credibility, what I’m looking for is the level of detail and information that is being shared and the consistency of that information,” Gross said. “And sometimes we’ve had situations where what has occurred may be a pattern in behavior. So you don’t have just one incident but you have more than one with maybe more than one person. That factors into credibility as well.”

Trust is earned through transparency; as long as this information is hard to find, students may continue to fear retaliation or unfair treatment when coming forward. Disclosing this process also ensures fairness in the investigation and prevents parties involved from being wrongfully penalized. This step may also reassure parents and help reduce the stigma around reporting sexual harassment in certain homes.

BP 5145.7 also mandates that information about the rights of parents and guardians to file a civil lawsuit should be made readily available. Until the start of the 2020-2021 school year, however, this information was not clearly conveyed, and even then, the policy was only explicitly touched upon once during the homeroom learning module.

While it is good that the policy has been disclosed now, more can be done by the district to make this information more accessible. In 2018, the district began to put mental health resources on the backs of ID cards. Distributing ID cards with the numbers of district Title IX coordinators in the same manner is just one example of how the district could increase accessibility to these resources. Small steps like these not only make it easier to report harassment, but also lessen the stigma behind seeking help.

“The way that people treat it right now is like it’s an inconvenience to report,” Ong said. “There’s a systemic issue of a lack of compassion, I guess, when it comes to reporting this stuff.”

BP 5145.7 also states that even if a crime is committed off campus and outside the district’s jurisdiction, it still has the right to launch an investigation if the victim’s school environment is disrupted. Although FUHSD is making significant progress by making resources more available to its students, some individuals who approached the district about being assaulted report being turned away by district officials.

“When I was attending Fremont, it kind of felt like they wanted to keep it private about what was happening,” Rivera said. “And whenever I did try to go to the district myself, [they] would just tell me, ‘Oh, you know, handle it with the police.’ So it’s like they didn’t really want to be a part of it.”

It takes a tremendous amount of courage for a survivor to come forward with their experience. Although this may very well be an isolated incident, the district should make sure that cases like Rivera’s don’t fall through the cracks and ensure that all complainants receive a chance at justice. Changing policy doesn’t mean much if district officials don’t actively make an effort every day to foster a welcoming environment for harassment survivors seeking to report.

While an investigation is ongoing, FUHSD leadership puts interim measures in place that are designed to preserve a normal learning environment for both the complainant and the respondent. These measures include mapping out routes for travel during passing periods, giving both parties an opportunity to talk with a school-based therapist and signing no-contact contracts. These interim measures are harder to enforce, however, if students are in the same classroom.

“During that interim time, it’s not right or fair for me to move the respondent out of class because I would be declaring him guilty before giving them an opportunity to say their side of the story,” Gross said.

Despite those concerns, removing the accused party from class can in fact be a key step to ensuring a safe learning environment for both the complainant and respondent. Because the district’s first responsibility is to preserve the learning environment for both students, removing one or both students from a class temporarily is the best way to ensure safety for both parties when investigators don’t know the full story. Instead of viewing the removal of students from classes as a direct accusation, district officials should look to protect both complainants and respondents wherever possible.

On Dec. 2, two individuals posted on Instagram about their abusive relationships with an unnamed Lynbrook Class of 2019 alumnus, referred to as “E” online. These abusive relationships allegedly consisted of regular sexual assault and battery. One of the survivors, Class of 2019 alumna Elaine Wang, was in a relationship with “E” in 2017 while a junior at Lynbrook. Although Wang reported the abuse to Lynbrook administration and local authorities when it occurred, she believes that insufficient disciplinary action was taken against her abuser. While at Lynbrook, Wang had to endure harassment and taunting from several classmates, who called her a b*tch to her face and told her she deserved to get raped. One classmate even spray painted derogatory graffiti on a concrete wall. After she shared her story on Instagram, however, Lynbrook students were shocked.

“I didn’t expect [any students] to do anything on my behalf at the time [of the relationship], but I think a lot of people knew what was happening but it was kept under wraps,” Wang said. “I didn’t mind that people didn’t talk about it, but having a lot of people now say that they couldn’t believe that this person was with them in these classes is a little disappointing.”

Some students at Lynbrook, and around the district at large, carry the perception that FUHSD is largely safe from issues like sexual harassment and assault. Many come to this conclusion because of the minimal amount of visible hatred, bigotry or discrimination that occurs on campuses. However, cases like Wang’s show that there is still much work to be done. There are still elements of Lynbrook’s student culture that actively perpetuate sexist and misogynistic environments.

“When I was in high school, it was common for girls to not really have privacy between them and their partner sexually,” said Lynbrook Class of 2019 alumna Selena Jeong. “There’s a culture where boys will use the things they do with their significant other as a token to uplift their social status or masculinity, when it should really be just between them and their significant other. In these situations, it goes beyond the boundaries of the relationship and violates [the girl’s] privacy.”

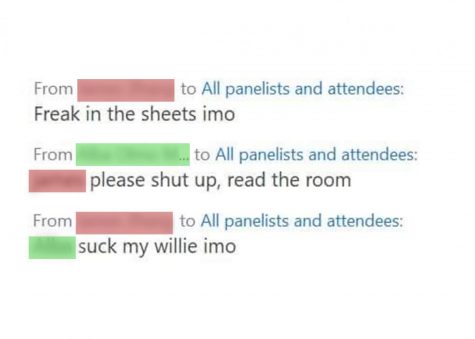

While the district has updated its policy and provides education through workshops and modules, its efforts will be squandered if students don’t understand the gravity of the issue. During the Center for Respect assembly, numerous students were removed for making light of the presenter and other classmates in the chat. In fact, some students were so disrespectful, the presenter was almost forced to turn the chat off. Many of these students believed that while the information provided was valuable, the content wasn’t relatable to Lynbrook students. After the assembly, student-run meme accounts, such as Instagram account @lynbrook.memes, posted their thoughts on the content.

“While I understand Center for Respect’s curriculum is probably made for a wide audience, such as schools around the country and colleges, I just found it hilarious that most of the assembly was talking about [party culture], something that Lynbrook students don’t really face,” said the owner of the @lynbrook.memes account. “To me, most of the content didn’t seem relatable to the average Lynbrook student.”

Even though the assembly’s presentation and roll-out may have been smoother in a non-remote setting, students have no excuse to openly mock the very serious topics at hand. Even if these lessons may not directly apply to some parts of Lynbrook’s campus culture, they are still valuable and have practical applications after high school. For progress to be made, students need to have an active hand in reforming their own campus culture. This involves not just listening during an assembly, but applying those lessons in real life.

“I feel like the community was silent because they didn’t know how to handle it and that’s fine, but I’d rather someone be honest and say that they didn’t know how to deal with it rather than just saying, ‘Oh my god, I feel so bad that this guy went to our school,’” Wang said, regarding the student reaction to her experience.

Like the Center for Respect assembly emphasized, it is not enough for students to be bystanders. Students should be condemning their peers for making jokes at the assembly. They should be learning how to actively prevent sexual assault and best support survivors. If students aren’t willing to participate in a one-hour workshop without making jokes, how are they going to stand up for one another when abuse happens to someone they care about?

“It’s not something that if you report, it’s going to be done and then you’re going to be fine,” Ong said. “This is something that’s going to affect the victim on a daily basis. Yes, this is an inconvenience to have to handle the paperwork and the recording and the classroom shifting, but it’s gonna be infinitely harder for the victim. They live with it for the rest of their life, especially when going to the same school as their abuser.”

While the district is now Title IX compliant and starting to take steps in the right direction, the job is never done. Updating policy is not the end goal: creating a safer environment for students across FUHSD’s campuses is. The district has offered a helping hand to its survivors in policy; now, it’s up to both district officials and students on campus to maintain an environment of respect, safety and dignity in practice.

*The Epic staff voted 38-0 in favor of this stance.

If you or someone you know is being sexually assaulted or harassed, please contact a trusted adult on campus. This can be a teacher, a campus-based therapist, a guidance counselor or a school psychologist. If you want to file an official complaint, please contact Trudy Gross at [email protected] or call at (408)-522-2203. More information on Title IX in FUHSD can be found here. If you require immediate assistance, call Uplift at (408)-379-9085 or the National Sexual Assault hotline at (800)-656-HOPE.