From Harvard to Proposition 16: The truth about race-based affirmative action in higher education

Anderson Memorial Bridge in Cambridge, Massachusetts: home to Harvard University.

November 12, 2020

Walking past Lynbrook High School, one cannot miss the modern, remodeled campus, the lines of Teslas in the parking lot and students scrolling on their new iPhones. Not too far away, though, are underfunded schools with students attempting to learn in run-down buildings and lacking the resources needed to receive the same caliber of education as those just blocks away. Living in an affluent corner of Silicon Valley, many Lynbrook students are not aware of the systemic inequalities and disparities that knock on doors throughout the country.

“When we look at what’s happening in the nation, we’re actually caught in the throes of two very lethal and dangerous pandemics,” California State Controller Betty Yee said in an Oct. 6 virtual event hosted by the California Democratic Party. “One is highly infectious, and it is the novel coronavirus. But the other pandemic that we’re also facing as a nation is systemic inequality and racism.”

In modern U.S. history, one of the first steps taken to address inequality was President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 Executive Order 10925, which introduced the term “affirmative action.” Following Kennedy’s assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson signed Executive Order 11246 in 1965 that mandated equal treatment under the law, regardless of race, gender, religion or national origin. Since then, affirmative action has developed largely under the courts, with influential rulings largely deciding how existing laws can be applied.

Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute defines affirmative action as a set of procedures that attempt to eliminate, remedy and prevent discrimination. It can apply to educational admissions and professional employment, among others, and remedy discrimination based on race, ethnicity, sex and religion.

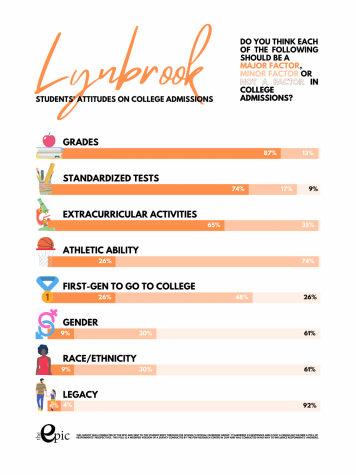

Although the term affirmative action addresses more than race, race-based affirmative action is experiencing the most controversy. In a survey of 23 Lynbrook students conducted in September and October 2020, 39% of respondents said that they believed race should be a factor in college admissions, while 61% believed that it should not.

To better understand the issue, it is important to delve into current events regarding the issue and the common arguments put forth in favor of and against race-based affirmative action.

Diversity

“I support affirmative action because it gives greater equity to marginalized groups and supports diversity,” junior Rachana Aluri said. “It allows disadvantaged groups and people to improve their lives and break the cycle of poverty, and it awards them the same opportunities as the more privileged.”

Many like Aluri believe that race, among other factors, should be taken into consideration in college admissions and job hiring because America should promote diversity. In the study “Effects of Racial Diversity on Complex Thinking in College Students,” published by Psychological Science, researchers found that the wide array of perspectives on diverse college campuses helped promote creativity. This supported the argument that diverse environments are more open and vibrant because diversity bridges social divides and brings out a multitude of perspectives.

Critics of race-based affirmative action agree with the importance of diversity; however, they argue that addressing these systemic inequalities should begin earlier on in life.

“Of course, opponents of race-based affirmative action want to help more underrepresented minorities,” Cupertino City Councilmember Liang-Fang Chao said. “But then that should be done by helping them to be stronger applicants and to develop those skills that can help them be successful.”

Advancement

Those who support race-based affirmative action note that it empowers underprivileged students, amasses equity and promotes minority advancement. With historically disadvantaged groups competing on an uneven playing field, race-based affirmative action can help families overcome disparity and ensure that students are not confined to their parents’ socioeconomic status.

A common counter-argument to supporters’ claims is that race does not necessarily determine whether an individual needs help or not. For example, an under-privileged white applicant would likely need more consideration than an affluent black applicant, even if this situation is statistically less common. As a result, people who oppose the program believe that considering race to promote the advancement of underrepresented minorities is a logical fallacy, as it does not adequately address the disparities that affect all Americans.

Regarding the impact of race-based affirmative action, proponents are correct in that competitive underrepresented minorities who make it to prestigious colleges significantly benefit from the opportunity. However, there is little evidence to suggest that the program significantly impacts students attending less prestigious schools. The Review of Economics and Statistics’ 2012 study, “The Effects of Affirmative Action Bans on College Enrollment, Educational Attainment and the Demographic Composition of Universities,” found that race-based affirmative action bans in schools with an admissions rate of around 60% would reduce Black representation by 1.19% and Hispanic proportions by 1.58%, which is significantly lower than the 2.15% and 4.16% decreases for more prestigious schools that have an admissions rate of approximately 30%.

“Much of the focus is on those top universities,” Peter Arcidiacono, Professor of Economics at Duke University and an expert witness in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, said in an email. “But most people do not attend one of those schools. Affirmative action at the schools does little to combat racial inequality, both because so few students attend these schools and because the benefits primarily flow to students who are already advantaged.”

Stereotypes

On the other side of the debate, some worry that race-based affirmative action can unintentionally hurt those whom it seeks to benefit. Critics point out that the program creates an atmosphere in which the success of underrepresented minorities is attributed to their race instead of their talent, skills or effort. As a result, the thought of being an “affirmative action admit” may haunt individuals, crush their confidence and diminish their accomplishments.

“For example, if I were selected to sit on a board because I am a woman, then, what are other people going to think?” Chao said. “They are going to think, ‘Oh, she must have gotten this seat because she is a woman,’ regardless of whether I am qualified or even overqualified. It doesn’t matter.”

However, others believe that affirmative action can help end stereotypes by creating diversity and inclusivity. Because exposure to others from different backgrounds creates understanding, proponents argue that increasing diversity through affirmative action can address the negative stereotypes placed upon underrepresented groups.

“I think there is a relationship between how we don’t have the opportunity to deepen our understanding of other communities to when we can’t be in an environment where we can learn together, understand each other’s histories, look at how we could come together and fight the injustices that have, frankly, affected all communities of color,” Yee said. “I think this is really one of the great things of what’s happening today in terms of the elevated voices around trying to fight for racial equity and justice.”

Reverse Discrimination

The most pronounced criticism of race-based affirmative action is that it attempts to mitigate discrimination with more discrimination, often known as “reverse discrimination.” People of color face unparalleled struggles, but some see that giving them “boosts,” no matter how good the intention is, is inequitable and discriminatory because it comes at the cost of others.

“It seems unfair to me that even if I work really hard to earn my grades and test scores and have dedicated a significant amount of time and effort into my volunteer hours, extracurricular activities, hobbies and other life experiences, I can be denied access to a college I want to go to because of my race or gender or family background,” junior Hana Yung said. “I feel like affirmative action bases college admissions on factors that individual students cannot control and undermines the things that they did do and the work they put in.”

Because America was founded on the principles of equal treatment under the law, some feel that using race as a factor violates that cornerstone. However, the courts have ruled that considering race does not violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment because it is merely one of many factors that are considered in admissions. Additionally, many supporters believe that race-based affirmative action is about more than college admissions. It is about the future of the nation.

“This has been very prevalent in my own community, the AAPI community, about every parent wanting their child to get into top-rated universities,” Yee said. “Frankly, I push back. Let’s be more aspirational — it’s about more than just getting into college. It’s about what our life and society are going to look like and our own contributions in terms of being able to provide leadership and even representation.”

Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard University

Many in the Asian American community oppose race-based affirmative action and joined Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) in filing a lawsuit against Harvard University in 2014. Claiming that the school discriminates against Asian American applicants in the admissions process, SFFA brought up examples of applicants who were denied admission despite having had better academic records and extracurricular activities than others from different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

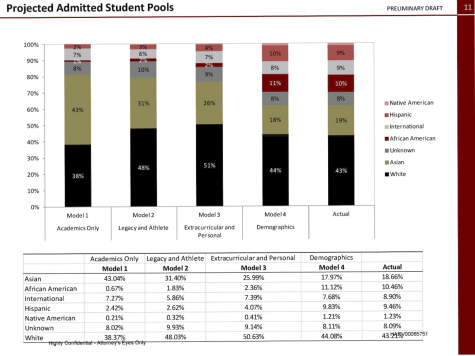

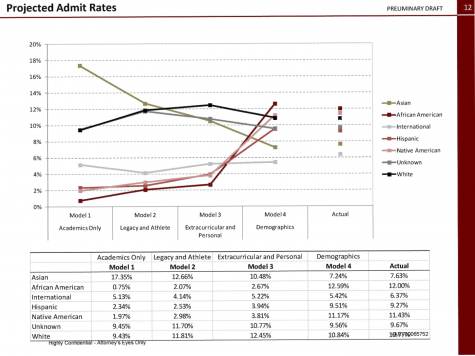

As part of the case, Harvard was forced to disclose confidential information, including a highly confidential internal study which revealed that, if only considering academics, Asian Americans would have made up 43% of the projected admitted student pool, as compared to the actual 19% in 2012. Even considering legacy, athletics, extracurricular activities and personal ratings, the study revealed that Asian Americans would still have made up 26% of admitted students without the consideration of race. On the other hand, white applicants significantly benefited from Harvard’s practices. If only academics were considered, white applicants would have made up only 38% of the admitted pool, compared to the actual 43%, but adding factors like legacy, athletics, extracurricular activities and personal ratings pushed the number above 51%.

In a paper that backed Harvard’s claim, David Card, Professor of Economics at University of California at Berkeley (UC Berkeley), explained that this occurs because Asian Americans tend to be weaker in the non-academic areas of Harvard’s admissions process, while white applicants are “more likely to exhibit multi-dimensional excellence.” Accordingly, the projected admitted percentages decrease for Asian Americans and increase for whites as those factors are considered. As so, Card argued that Harvard does not discriminate against Asian Americans.

However, Peter Arcidiacono, Professor of Economics at Duke University, questioned why Asian Americans score lower on personal ratings and overall ratings, both subjective factors that are completely up to the discretion of admissions officers.

“I think Harvard uses these as a way to achieve racial balancing,” Arcidiacono said. “Asian Americans are doing way better than any other group academically, so they have to invent ways to keep them out in an effort to have their enrollees look more like the U.S. population.”

Although many scholars like Card argue that Harvard does not discriminate against Asian Americans, Arcidiacono believes that those individuals think otherwise.

“I don’t think they actually believe that,” Arcidiacono said. “I think they are willing to say that to save affirmative action. The case that Harvard discriminates against Asian Americans is overwhelming.”

Although the U.S. First Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Harvard on Nov. 12, 2020, people speculate that it may reach the U.S. Supreme Court, in which case the new conservative majority may have the final say on the matter. Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard is merely one of the many cases detailing discrimination against Asian Americans. Arcidiacono is also an expert witness in Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, and the Trump Justice Department recently claimed that Yale University discriminates against Asian American applicants.

Card declined to comment for this story.

Proposition 16

On the other hand, California lawmakers in Sacramento passed ACA-5, a proposal that would allow the state government to consider race, sex and ethnicity in public education, employment and contracting decisions, on June 25. ACA-5 passed the Assembly 60-14 and the Senate 30-10, and it was on the November 2020 ballot as Proposition 16. It attempted to repeal Proposition 209, which passed in 1996 and banned race-, sex- and ethnicity-based affirmative action; however, Californians rejected the proposal with 56% voting against the proposition.

Because Proposition 16 would have allowed the University of California (UC) system to reinstate race-based affirmative action, many Lynbrook students and parents worried that it would affect students’ admissions prospects. As one of the top feeder schools to UC Berkeley and the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) and with an 88% Asian American student body, Lynbrook students would have been significantly affected by the change. In a school-wide mock election in which 633 students participated, 36% of Lynbrook students voted yes on the proposition, while 67% voted no.

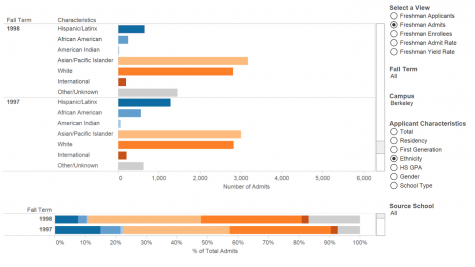

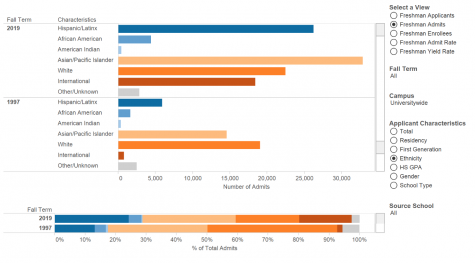

Despite having low support among Lynbrook students, the campaign “Yes on Prop 16: Opportunities for All” gained support from the likes of Sen. Kamala Harris, Gov. Gavin Newsom and Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who hoped that passing Proposition 16 could create opportunities for all and reverse the impact of Proposition 209, which led the percentage of Black and Hispanic students admitted to UC Berkeley to drop from 7% and 15%, respectively, in the fall of 1997 to 3% and 8% in the following year. Before the election, Yee passionately argued in favor of the proposal.

“For almost 25 years now, we have seen our communities of color and women incur a lot of setbacks,” Yee said. “There’s a lot of very, very unfortunate myths that are moving around Proposition 16. This proposition does not establish quotas. All we’re saying is that we want everyone to have equal opportunity.”

Chao countered that the UCs should expand already-existing programs that were created to help underprivileged students, mostly people of color, because they cannot consider race in admissions.

“A couple of years after the ban, underrepresented minorities had a big drop in the UCs and in business contracts in government,” Chao said. “As a result, the government took steps to roll out programs that helped them to become better employees and better students because they will have to be judged at the same standards.”

It is also true that since the passage of Proposition 209, the percentage of admitted students from Hispanic backgrounds to the UCs nearly doubled from 13% in 1997 to 24% in 2019. Still, consensus and statistical evidence show that Proposition 16 and race-based affirmative action would have further increased Black and Hispanic representation in prestigious UCs like UC Berkeley and UCLA; however, it would not have significantly increased the proportion of underrepresented minorities in other UCs because they are almost proportionally represented in the schools.

The percentage of Asian Americans among admitted students, 42% and 38% for UC Berkeley and UCLA’s Class of 2023, respectively, would likely have plummeted, leading many to feel that race-based affirmative action is not adequately helping students of all backgrounds but, instead, discriminating against certain groups.

“Rather than race-based policies, lower-income school districts should get more funding,” senior Anoushka Naik said. “We should equalize K-12 education for all public school districts. Until absolute equality can be achieved in the school system, affirmative action should be based upon family income, not race.”

Some critics of race-based affirmative action propose action taken based on socioeconomic status instead, as it benefits all those who need help, regardless of their background. They believe that poverty affects all Americans, regardless of their race. However, supporters of race-based affirmative action stand behind its effectiveness.

“Superficially, this would make sense, but it is just naive to think socioeconomic conditions are the only impediments in people’s lives,” Aluri said. “To think that socioeconomic status is the only thing holding some groups back is wrong. Race discrimination is a huge part of this country, and it is imperative that it be considered in the affirmative action process.”

How should America achieve diversity, equality and equity? How should it aspire to and adhere to its philosophical, legal and ethical principle that “all men are created equal”? For decades, Americans have debated the issue while trying to remain true to America’s founding principles of liberty, freedom and justice for all. The will to create a united and just society for all is not beyond America’s reach, but the question that Americans need to decide remains — will race-based affirmative action do that?