The CAA and NRC are taking away India’s secular nature

January 29, 2020

Every morning, students across India recite the country’s National Pledge. It begins, “India is my country and all Indians are my brothers and sisters.” The pledge celebrates the country’s democracy and constitution, as well as its traditions and history. On Dec. 9, however, the pledge found a new meaning when the country woke up to the announcement that the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) was to be signed within three days. The law clashes not only with the pledge’s values, but also with India’s constitutional principles of secularism and equality.

CAA is an amendment to the Citizenship Act of 1955, which details the requirements for a refugee to be considered an Indian citizen, including factors such as length of residency as well as other specifications. The CAA is the first act to consider religion when reviewing refugee status and citizenship, contradicting the country’s most touted ideal of secularism; it states that only Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from India’s neighboring, Muslim-majority countries of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh will be eligible to gain citizenship within five years of living in India, instead of the previous requirement of 11 years.

The act does not account for other minorities, such as Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar, Sri Lankan Tamils and any Muslim seeking refuge or looking for opportunity in India, because it directly states that the only factors that would allows an individual to gain expedited citizenship are being members of the specific religions and the three countries.

Bharatiya Janata Party (translated as the “Indian People’s Party”, BJP), the ruling party, also announced the possible creation of a National Register Citizens (NRC) by 2021, a database for all the legal citizens of the country. NRC requires that those seeking to prove their citizenship provide evidence of ancestors’ Indian citizenship. In April 2019, the president of BJP, Amit Shah, tweeted, “We will remove every single infiltrator from the country, except [Buddhists], Hindus and Sikhs.” In the context of BJP’s past statements and Hindutva, or far-right Hindu nationalism, ideologies, Shah implied that the “infiltrators” were Muslims, primarily because their religion was not created in India. This belief is especially worrisome as Muslims make up more than 15 percent of the country’s population of 1.3 billion, amounting to more than 200 million people.

The NRC is a mutated form of ethnic cleansing, as it aims to not only exclude Muslims but also those of lower socioeconomic status. Many people in poverty do not have access to ancestral proof or even the means to find it, resulting in an almost direct displacement from their homes. In October 2019, NRC was implemented as a trial in the northeastern state of Assam, resulting , as more than two million people were displaced; the majority of the displaced were actually Bengali Hindus, thus not even fulfilling BJP’s “nationalistic” notions.

“If you think about the intersection between socioeconomic status and religion, the people on the bottom of the list are Muslims because they have been discriminated against over generations,” said Hatim Saifee, a Lynbrook alum. “But, that does not mean there aren’t other groups with low socioeconomic status. So, no one can really be disregarded.”

By excluding these minorities, the act has become the latest installment in the actions of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his party that further the “Hindutva” ideology. This ideology is the conservative and somewhat extreme belief in Hindu nationalism and hegemony, or the dominance of Hindu nationalists over all other groups. It has become a prominent characteristic of the rhetoric of the ruling party.

Although the dates from when the CAA will go into effect and the bill for the NRC will be signed have not yet been announced yet, the two acts have resulted in massive protests within India and around the world. In northeastern India, indigenous populations are protesting as they believe they will lose their opportunities to Bangladeshi immigrants who can easily enter their states. In northern India, college students at Aligarh Muslim University, Jamia Millia Islamia and Jawaharlal Nehru University began holding protests soon after the announcement of CAA and NRC, fearing the development of a fascist government. Soon after, police attempted to curtail the massive protests with violence, using stones, tear gas and stun grenades, as well as arresting any dissenters. Many have been seriously injured, at least 27 people have lost their lives and more than a 1000 people have been arrested.

The government and police’s violent and ignorant response to the protests has led to a lot of fear and displacement within the Muslim community in India. Riots, especially in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, have not only claimed lives and disabled many people, but have also led to the complete desertion of many villages. Similar events in the past led to government aid for the victimized. But, this time, the people are not so lucky: the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, Yogi Adityanath, is a Hindu priest appointed by Modi and a flagbearer for inflammatory, Hindutva rhetoric.

“There have been people I have met who had to live out of a water tank to hide from similar riots in the past,” said junior Haadia Tanveer. “It is just scary, because no one knows what they are going to do, especially because it is so hard to even immigrate.”

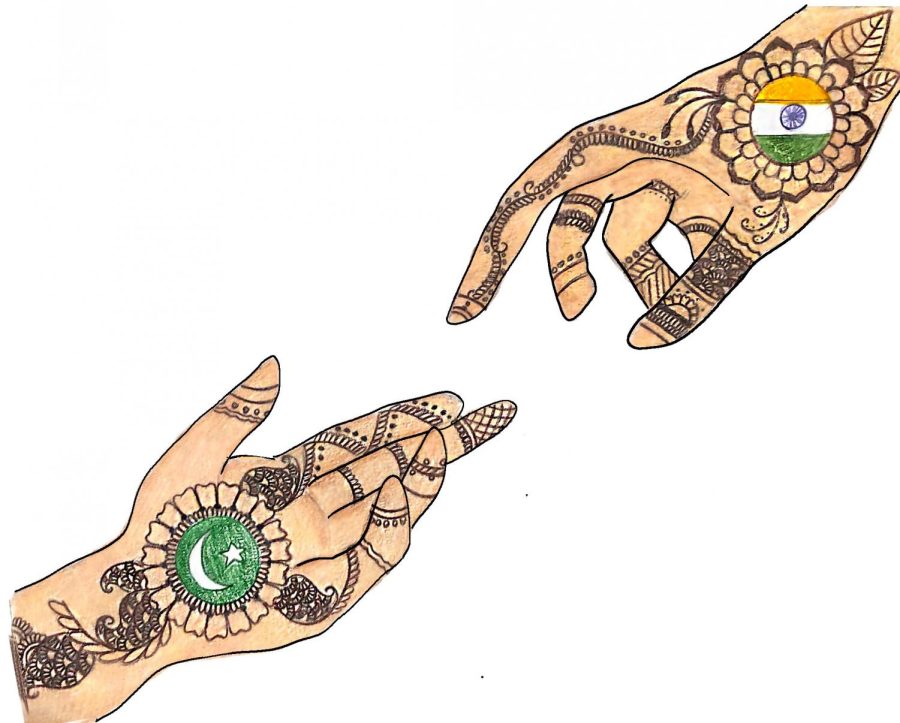

The protests in India have been growing in intensity almost every day after the announcement of the acts, and the issue has also sparked many international protests: students from universities like Columbia and University of California, Berkeley have demonstrated on campus, as have citizens in cities like London and San Francisco. Although there are many different groups protesting, from affected Muslims to concerned citizens, unity among all has become the most powerful and hopeful characteristic of all the protests.

“I see the protests as a sign of hope,” said Saifee. “To me, it signifies that the public is starting to become aware of the complicated situation. It just shows that the public has a mind of its own and hopefully that puts pressure on the government.”

The future for India and its government is uncertain. The protesters, wary of the creation of an authoritarian state with a failing economy, have been courageously persisting, with protests being held around the country almost on a daily basis. Meanwhile, Modi’s government has been enacting laws that punish sedition, or speaking against the establishment, as well as enacting military law in certain parts of the country. Internet shutdowns, another of Modi’s common defenses, are also being implemented in parts of the country.

“In today’s day and age, having access to the internet is as fundamental as having access to water,” said history teacher Steven Roy. “I do not think [any government] should have the power to take that away except under extreme circumstances.”

The protests are not about dissent anymore, but instead are about the fight for basic rights. Even though there are four more years before the next general election in 2024, the progress of the country, either toward democracy or fascism, depends on the power of the protesters and politicians fighting against NRC and CAA. History has proven that far-right nationalism and authoritarian government are almost always detrimental to the wellbeing of the people. With 1.3 billion in India and 15 percent being Muslims, the magnitude of India’s direction toward either improved inclusivity or destructive divisiveness is especially huge; the protesters now have the power to create a future that embraces diversity and secularism, not only in India but around the world.

Jay • Jun 17, 2020 at 6:53 am

I am a British born Bengali and currently trying to research Kashmir with a blank slate and open mind as to understand the complexities of the region; to ascertain as to why so called intelligent nations struggle for peace based on human values. Your article is very good because as I’ve been researching, the learning has taken me to India and Pakistan’s current domestic and foreign policies. The challenge I have is that it is next to impossible to find unbiased literature on anything remotely related to Kashmir. Furthermore, it is as difficult to find unbiased literature on both the Pakistan and India governments. Your article is one of the first that seems to provide a balanced and factual based view of ones own country and its government. Democracy is based on the government working for the people and answering to its people. In India currently it is suggested that its the other way round and to complicate it further it is obvious by reading various papers, the actions taken by the Indian government in the last 12 months at least has similarities to Germany in the 1930s. It would be good for my education and learning to have the chance to speak to a someone like yourself to gain an unbiased view because I believe the majority of British born Asians have little understanding of the truths of ones own mother country and tend to follow propaganda provided by their peers.