Changes in ADU laws help provide affordable housing

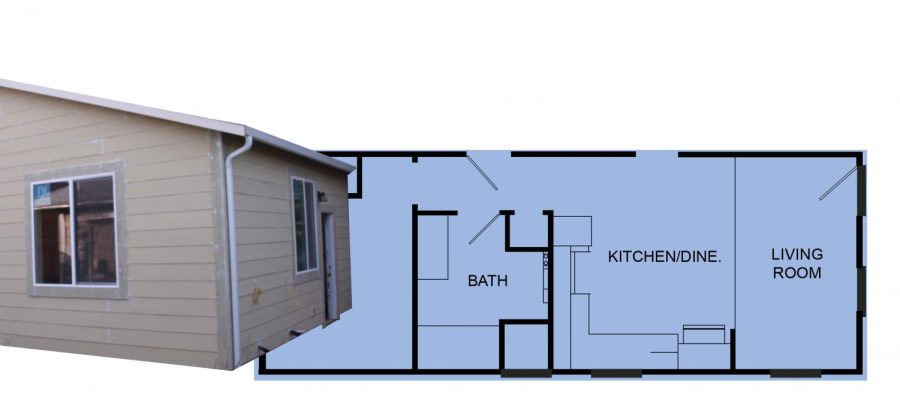

Photo and graphic of an example house blueprint

January 29, 2020

West San Jose holds the title of being one of the most expensive areas in the nation. With the current average house price standing at roughly $1.5 million and peaking at $1.6 million in 2019, the housing crisis has driven thousands out of the city. The lack of affordable housing is a widespread issue in California and has caused the state to examine the development of accessory dwelling units (ADUs) as a solution to help people with median and low incomes.

ADUs, also known colloquially as “in-law units” or “granny-homes,” are small living units that are built on the property of a single home. They are usually around 750 square feet and have their own home address. ADUs can either have their own separate utilities or share utilities with the main house.

On Jan. 1, California state legislators enacted Senate Bill 13 (SB13) to facilitate the development of ADUs and provide amnesty for unauthorized ADUs — units that have not been legally approved and registered to become compliant with state standards. To help lower the cost of building ADUs, SB13 waives the development impact fees paid to the local government for ADUs smaller than 750 square feet. These impact fees help offset the financial cost of new growth in the community and include parkland and school fees.

Although there is a possibility that homeowners may abuse the protections offered by SB13, the City of San Jose has already placed multiple restrictions to protect ADU residents. First and foremost, the city mandates the safety of all ADU residents and requires all homeowners intending to build an ADU to meet certain health and safety requirements. In addition, San Jose homeowners are required to work with the city’s third party consultant and an ADU amnesty coordinator to perform a pre-application inspection of the unit, a permit application review and a final inspection before the homeowner can submit their ADU application to the city.

“Many ADUs have violations related to electrical lines, which is a big safety concern,” councilmember Pam Foley said. “The amnesty program allows homeowners to make their units safe with few repercussions.”

San Jose lawmakers originally brought up discussions about ADUs and amnesty for owners without permits in 2017; however, the finalized law was not brought into effect until Jan. 7. The San Jose amnesty program waives certain fees and taxes, such as a business license tax and a penalty fee for unpermitted construction. City officials estimate that 50 permit fees for ADUs can be waived this fiscal year, averaging $5,862 per application and totaling $293,000 in waived fees. In the fiscal 2020-2021 year, the city will accept 100 waived permit fee applications, totaling $586,200.

“ADU Amnesty helps us fully realize how many ADUs are in the City of San Jose,” said Senior Policy Aide Michael Lomio. “It adds to our housing stock by becoming officially recognized under our Regional Housing Needs Assessment count, and creates more safety. For instance, if an earthquake occurs, and an ADU is not up to code, that ADU is more likely to cause injury than a legalized ADU that is up to code.”

SB13 and the new San Jose amnesty law allow for the construction of more ADUs and their integration into the public market. ADUs are more affordable than many of the other housing options in San Jose, providing people with median and low incomes with an affordable alternative.