New CSU math requirements threaten equity

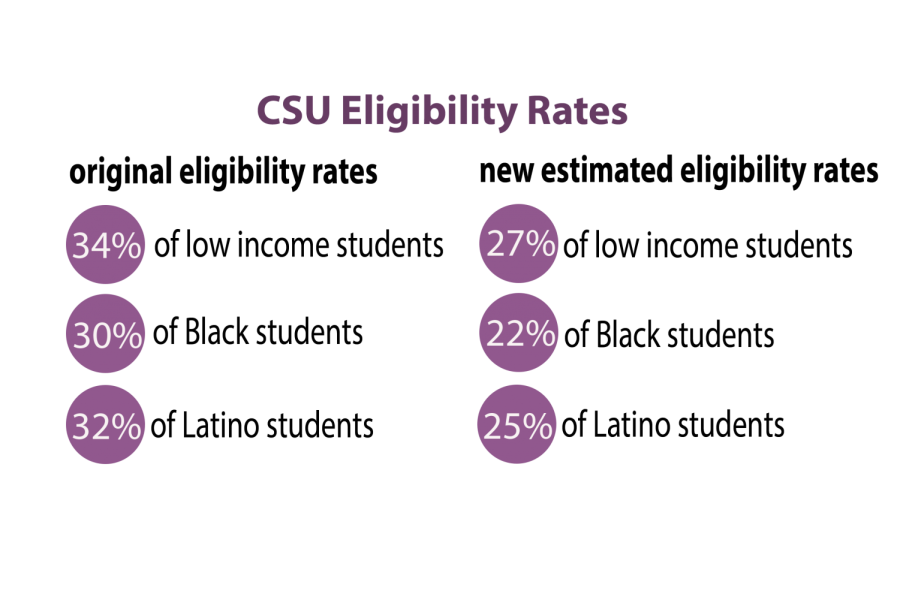

Eligibility rates for the California State University system with the new quantitative reasoning requirements are predicted to be lower than current rates.

November 6, 2019

For years, California high school students have only needed three years of quantitative reasoning classes, classes that require some degree of math, to be eligible for California State University (CSU), a public university system. However, that may soon change with a newly-proposed requirement for eligibility, for which a vote is scheduled for November by the CSU Board of Trustees. This requirement would add one more year of quantitative reasoning classes to the existing requirement, which is predicted to have negative consequences on various groups of high school students throughout California. Many have voiced concerns regarding the updated requirement’s equity. Its effects will be felt by students in districts that are struggling and those looking to pursue careers in humanities. These people, who by no fault of their own, are being put at a disadvantage. They are either obligated to obey a requirement that won’t help them in the future or, due to their school’s budget, have more difficulty taking the classes needed to fulfill the requirement

The requirement would be first implemented within the system’s freshman class of 2026. To meet it, students must take four years of quantitative reasoning classes in high school. This could be filled by traditional math courses or elective courses such as personal finance, computer science, forensics, engineering or sports medicine. Courses of this nature are offered by all comprehensive California high schools. The reasoning for the change is the additional year of quantitative reasoning class better prepares students for a career in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM). Further, a study conducted by CSU shows that students are more likely to return for their second year of college if they took four years of quantitative reasoning classes in high school.

At first glance, this change seems to be an improvement, but after closer analysis, the situation is more complicated than it appears. It would better prepare students looking at STEM careers, but to a person pursuing a career in humanities, it creates undue complications. The extra quantitative reasoning course would replace another class that could be of more benefit in the long run. A university should cater to the needs of all students, which is not exemplified by the new requirement.

“A lot of people are doing what they’re passionate about,” said freshman Esha Dasari. “Some people might not find a passion in mathematics and if they’re not passionate about these kinds of things, they shouldn’t have to do it.”

Even more concerning, schools in rural or low income neighborhoods often don’t have the resources to provide courses besides the traditional math and science ones. This disadvantages students at those schools, as it forces them into more mathematics and science courses, rather than a specialized elective course that would be more beneficial to their future and could also fulfill the requirement.

“I think it’s fine to raise the bar; we want our students to be held to high expectations,” said math teacher Chris Baugh. “But if implementing those changes widens the achievement gap, we have to question whether it’s having the intended effect. Are we making those that are more privileged, even more privileged because they’re able to perform, while sacrificing students who traditionally perform lower? We have to make sure we bring the bottom up.”

To prepare for a possible increase in teachers needed to teach the courses required, CSU is proposing to increase its Mathematics and Science Teacher Initiative. CSU trains many of California’s teachers and they hope by increasing the amount of people trained, they will be able to get all high schools up to the level of the new requirement by the time it is implemented. However, if CSU is already aware of the less than ideal state of some schools, they shouldn’t be waiting to train more teachers until after the new requirement is implemented, as this heavily strains already struggling schools. If the main focus is to improve California schools as a whole, there is no reason to wait.

Regardless, adding more math and science teachers could be beneficial since it allows for an increase in classes available. Nevertheless, it shouldn’t be only those departments receiving new teachers. It seems as if these new teachers are being trained solely to ensure students meet the requirement, rather than actually teaching them.

Another complication regards applications to the University of California system (UC) and CSU. In the past, since 2003, UC and CSU have had the same entry requirements for their colleges. By changing the quantitative reasoning classes requirement, CSU will have one more year required than UC’s three years. This could cause confusion for students hoping to apply to both, as some students qualifying for UC will not qualify for CSU.

Being prepared is important, however; the new requirement benefits only the students pursuing a career in STEM. Forcing people pursuing humanities to abide by a requirement that won’t help them in the future will hurt students more than it helps. Providing equal opportunity and limiting confusion when it comes to college applications is also an important part of preparing students for their future. CSU is well aware that California’s high schools are not all fully preparing their students for college; so rather than placing a greater burden on already struggling schools, they should opt for changing requirements once schools are able to shoulder the weight.