A 13-year-old boy fatally stabbed a 15-year-old boy at Santana Row in San José, Calif. on Feb. 14. Although places like Santana Row are typically thought to provide a safe space for teenagers to hang out, incidents like this have become a harsh reminder that these spaces are not always free from danger. Under California law, the accused faces a mere eight months in an unlocked juvenile facility — a consequence that is insufficient for a crime as severe as premeditated murder. The law fails to hold young offenders accountable for violent actions in a manner that matches the gravity of their crimes.

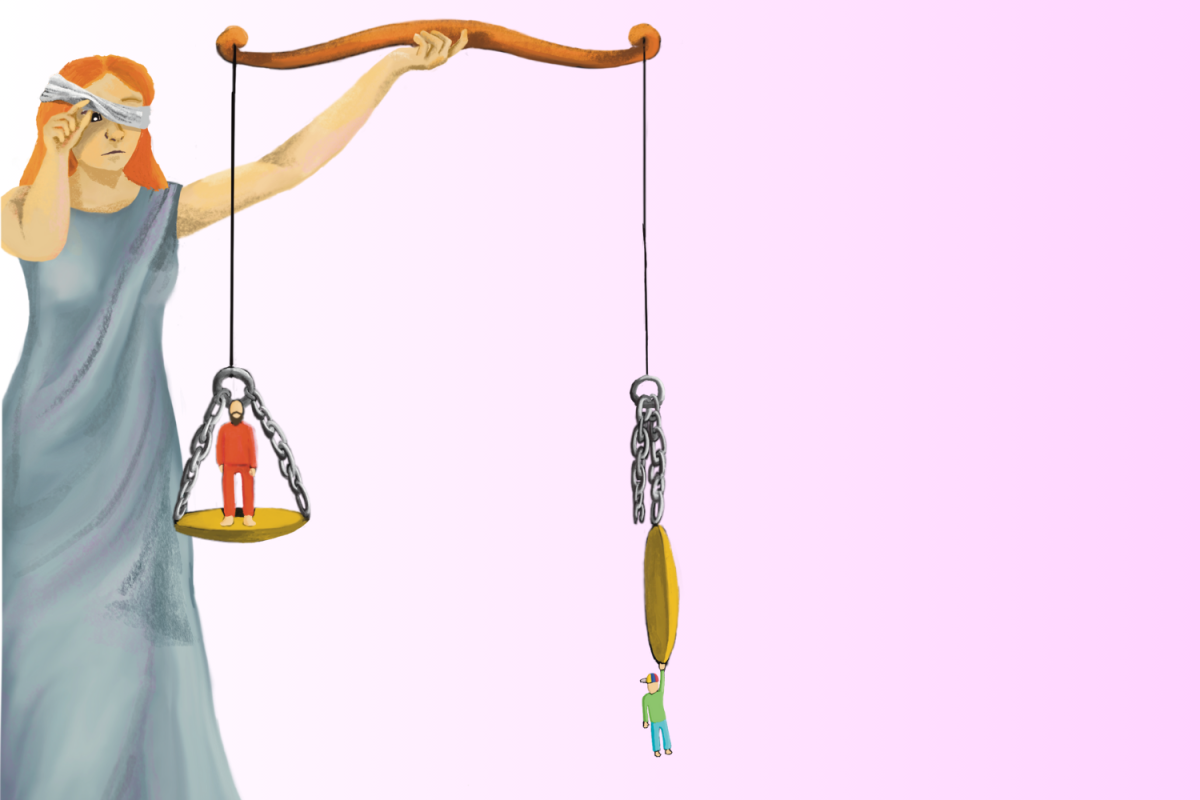

In recent years, California’s juvenile justice system has increasingly focused on rehabilitation rather than imposing harsh punishment, aiming to reform young offenders. Rehabilitation is crucial, but it has enabled gangs to exploit lenient laws by recruiting minors. In this case, it is alleged that the 13-year-old was recruited by the Sureno gang, who knew he would face lighter consequences due to his age. California’s Welfare and Institutions Code 707 dictates that juveniles under the age of 15 cannot be tried as adults, even for severe crimes like premeditated murder. This approach does not offer enough deterrence and fails to strike the right balance between rehabilitation and public safety.

“Adults, gangs, are exploiting the leniency of our juvenile system, recruiting underage members to commit horrific acts of violence on their behalf,” San José Police Department Chief Paul Joseph said during a news conference Feb. 17. “Why? Because they know that a 17-year-old, 15-year-old, even a 13-year-old is unlikely to face consequences anywhere near severe as an adult would for the very same crime.”

The Santana Row stabbing serves as a reminder that California’s juvenile justice laws underestimate the dangerous potential of violent juvenile offenders. In the case of gang-related violence, it is crucial that the legal system adjust its approach. For instance, juveniles under the age of 14 should face harsher consequences for violent crimes, such as being tried as adults when the crime involves premeditation or gang activity. A stronger penalty system could include longer sentences in secure facilities. These penalties should be enforced in a way that ensures public safety while still providing opportunities for rehabilitation, ensuring that youth who commit violent crimes understand the weight of their actions.

“If the punishment isn’t heavy enough for the crime, then that may not be enough of a deterrent,” social studies teacher Mike Williams said. “However, I also think that young people deserve some sort of special treatment when it comes to application of the law, because they’re not yet adults and may be affected by their environment in ways that they can’t rise above.”

Adults, too, must face the consequences of their actions. One potential solution to gang recruitment is ensuring repercussions for those who exploit young offenders, which could help break the cycle of youth recruitment by gangs and reduce the overall level of gang violence in California.

“This crime sets a dangerous precedent for gang violence and juvenile crime, where kids who commit serious crimes like murder only serve eight months, with no real repercussions or rehabilitation,” junior and mock trial co-president Samay Sikri said. “This not only fails to hold them accountable but also sends a message that the justice system will let them off too easily.”

Recent incidents within California’s juvenile facilities have exposed shortcomings in the system’s ability to protect and rehabilitate youth. A notable case involves Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall in Downey, where 30 detention officers were charged with child endangerment and abuse for allegedly facilitating 69 violent “gladiator fights” involving over 140 youths between July and December 2023. Moreover, the 2017 Division of Juvenile Justice Recidivism Report indicates that 34.3% of the youth released in Fiscal Year 2012-13 were returned to state custody within three years, with 16.6% being reincarcerated for crimes against persons. This statistic highlights the flaws in the current system and its failure to adequately rehabilitate and support these young individuals in breaking the cycle of crime and violence.

“We need a system that ensures accountability for young offenders, especially when they commit violent crimes,” Williams said. “Rehabilitation is important, but it can’t come at the cost of public safety.”

The juvenile justice system should be reformed to include both stronger punitive measures and comprehensive education. Enhanced accountability could deter future crimes, while educational programs and community service could equip them with the skills and mindset to lead a productive life post-incarceration. This way, the system can foster a generation of individuals who recognize the severity of their actions and are prepared to make meaningful contributions to society.

“Throwing someone in jail will teach them a lesson, but actually teaching them how to live a proper life, where they are not associated with gangs, and showing them that there is another pathway that isn’t violence, is also essential,” Sikri said. “Rehabilitation should come with education and real-life skills training to ensure that once juveniles leave the system, they are ready to contribute positively to society rather than return to old patterns.”