If you visit change.org, an online petitioning site, you’ll find a petition titled “No Homework” that has over 40,000 signatures. Another one advocating for no school after Halloween has over 70,000. In today’s digital age, petitions are a universally accessible way for students to voice their concerns and make an impact. However, with increased access to advocacy comes the responsibility of using it for positive, necessary change. When petitions are misused for jokes or to target individuals, they cause disruption rather than progress, with online spaces increasing the likelihood of counterproductive petitions that lack the credibility to address local and school issues.

Starting with the right approach to creating a petition is essential for positive change. Student petitions should use respectful language and support a positive educational environment. These student petitions should also be thoroughly researched by both students who start them and those who sign them. To make sure the petition is credible, students looking to start a petition can reach out to a staff member to help organize and fact-check the information they are putting forward.

“Petitions require work and communication,” science teacher Lester Leung said. “A petition without support or justifiable reasons lacks validity. A petition without prior discussion with related authority lacks seriousness.”

One notable example of a productive petition was started by Lynbrook’s French Honor Society, or SHF, advocating to preserve Miller Middle School’s French program. When they heard it might be cut for the 2024-25 school year, SHF started an online petition, sharing it through social media and Lynbrook’s French classes. This petition helped reignite the conversation about Miller’s French courses, and the Cupertino Unified School District ultimately decided to preserve them.

“The petition had a big role in clarifying misinformation that the students were hearing,” French teacher Elizabeth Louie said. “It was a great way to put an issue out to the community and clarify why it is important.”

While petitions can bring attention to a student’s concerns, they also help address misunderstandings in the community. When students are engaged and organized, they can inform decision-makers about changes they wish to see in their education.

“It’s definitely important to know all of the information regarding your case so that everything is accurate and you can be as transparent as possible,” SHF president Amine Ali Chaouche said. “Don’t be afraid to reach out to be administrators because your voice is important.”

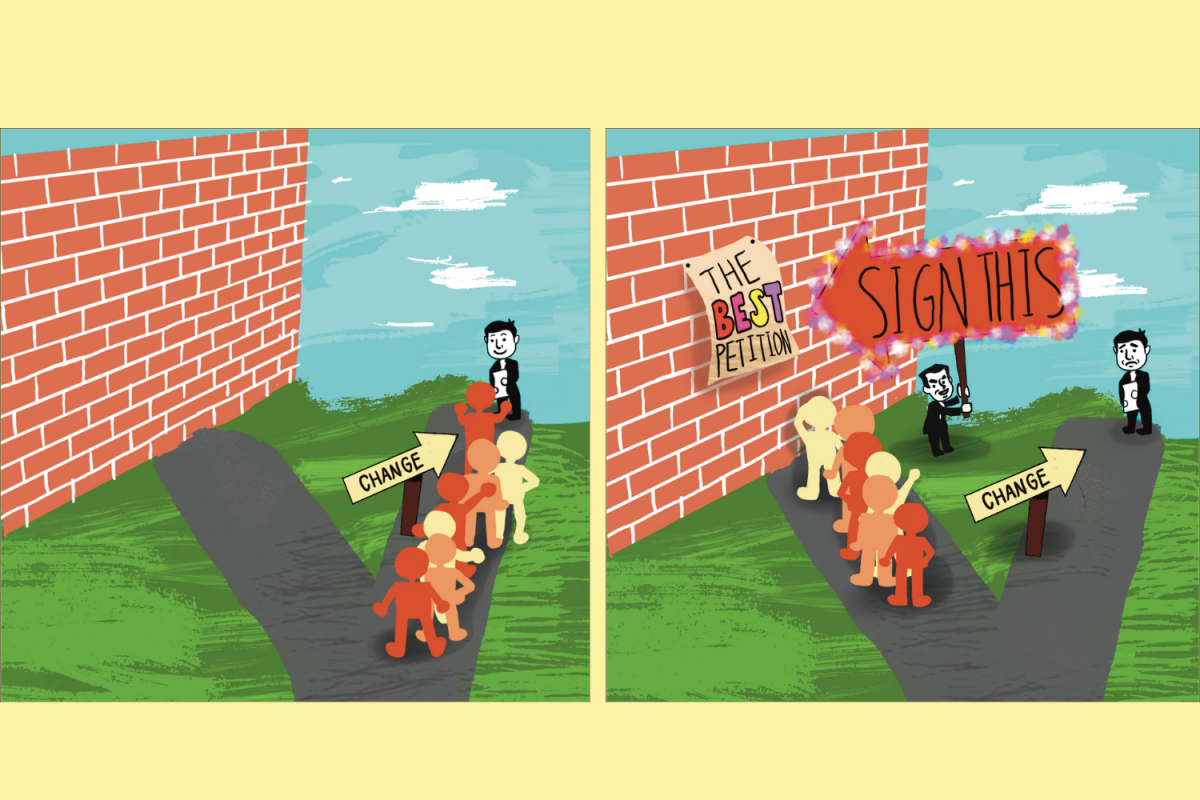

Another way students can use petitions responsibly is to recognize when a petition is not credible. Many online student petitions fail to make an impact because they lack credibility. On change.org, people c with fake names or sign multiple times with different email addresses. This makes the petition susceptible to inappropriate or unrelated comments because these online platforms usually do not require people to verify their identity. In addition, these petitions are available for anyone with internet access to sign, including those who don’t have any connection to Lynbrook. Online petitions can also suffer from a lack of student follow-up since they require less effort to make and are often abandoned by their creators. The purpose of a petition should be to eventually open communication with administrators, but an anonymous list of signatures on change.org does not contribute to making an impact.

“On change.org, it’s easy to get a lot of people to sign your petition,” FUHSD Superintendent Graham Clark said. “But do the people signing the petition really have all the information?”

Maintaining credibility in a petition can be as easy as starting a physical one, where the organizers can monitor students’ comments and know who they are getting input from. Getting signatures in person also maintains local, relevant input and attaches real names to an issue. This creates a community of people who strive toward the same goal, creating more unity when advocating for their cause.

“It’s really easy to spread misinformation online,” sophomore Albert Shao said. “I’ve seen online petitions that just aren’t true. But on paper, someone is there to oversee the signing.”

However, whether on paper or online, petitions can be subject to hurtful exploitation. Petitions that target specific individuals may attract a lot of attention and signatures but can create unnecessary conflict. In other cases, a petition may have been created out of genuine concern over an issue and escalates into a joke due to the signers’ counterproductive behavior such as leaving negative, “trolling” comments.

No matter how easy it is to anonymously post negative comments to insult another individual or cause, we should still be accountable for the words we put online, since everyone, including the person who is the subject in the petition, can view these comments. This means students organizing petitions should ensure that any input submitted is from a reliable source, and signers and commenters need to strive to curate well-thought-out contributions.

“It’s very concerning when people use a petition to take out their personal grievances, instead of looking at something that is a real issue,” Principal Maria Jackson said. “It uses a lot of resources to follow through on that and is hurtful to those involved.”

It is important to note that even when petitions are made responsibly and successfully, they are not a surefire solution to every community issue. They do not make decisions; rather, they serve as a tool to inform decision-makers about a community issue.

“Petitions inform us of public opinion,” Jackson said. “On the grand scale, it’s people making their voices heard at board meetings or by meeting with school leaders. It’s conversations with feeder schools. It’s looking at data. Petitions, alone, do not sway decision making.”

Petitions can be successful if we treat them as a patient, well-thought-out process involving research and communication. They have the potential to make a serious impact, but the administration will only respect the petition if we take them seriously ourselves. By treating the petitioning process with the respect it deserves, we increase our chances of being heard and making meaningful changes.

“Students are important stakeholders,” Louie said. “They are the people our schools are here to serve. Districts are more willing to listen to students than a suggestion from an individual teacher but it is important to know the petitions’ limits and implications.”