“Crash out,” “slay,” “basic” and “ate”: these are all widespread slang terms, often assumed to come from younger generations, the Internet or even brain rot. In reality, before they became mainstream lingo, many slang terms originated in marginalized communities as ingroup identity markers.

“A lot of slang is about identity,” said Dr. Anna Bax, assistant professor of linguistics at California State University, Long Beach. “Knowing the right slang for the particular social group you’re trying to blend in with is huge for building relationships with people and positioning yourself as an insider to that community.”

Even outside of groups like black and LGBTQ+ communities that have an outsized influence on mainstream vernacular, slang can strengthen a sense of cultural identity through informality and wordplay. In fact, this is one of its core functions: to differentiate members of a smaller “ingroup” from members of a dominant “outgroup” — in this case, the broader online mainstream — who look in as observers. More so than other forms of language, slang is a measure of belonging.

When outgroup members adopt ingroup slang, they’re often seeking to adopt desirable traits they associate with the ingroup, according to Bax. Sometimes, these traits are rooted in stereotypes. For example, the use of African American slang to seem more tough may stem from the stereotype of black people as violent and aggressive. Someone may use terms from LGBTQ+ communities to emulate the energy, wit and animosity of the tropey “gay best friend.” These motivations can be subconscious or purposeful.

Slang is uniquely slippery. Due to its role as a cultural demarcator, the speed at which it can disseminate and its primarily casual usage, it’s hard to tie down and track. As such, slang’s meanings can be fluid; as new words arise and existing words are repurposed for different contexts, definitions change. For example, the term “woke” is derived from the phrase “stay woke,” a call to action and awareness within black communities. Since then, it’s been folded into the language of mainstream politics, indicating progressive or leftist ideology, often in a derogatory sense.

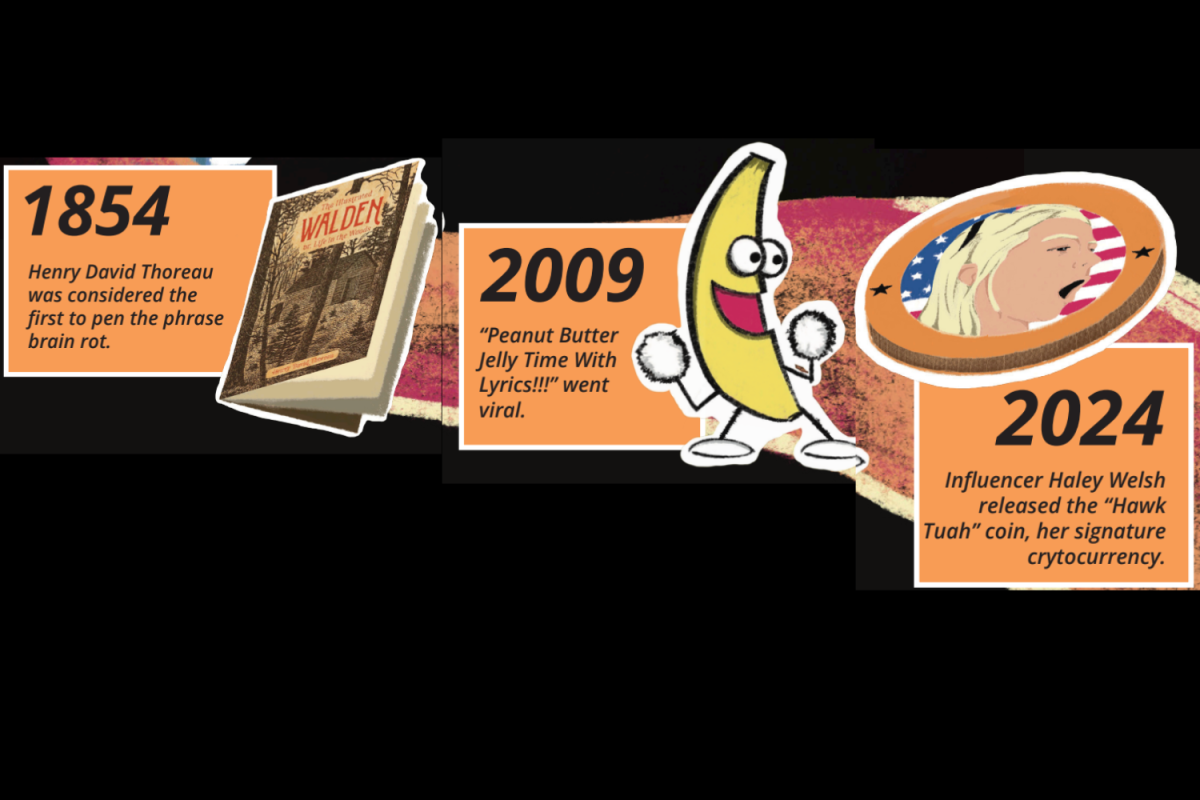

Slang’s diffusion from marginalized into mainstream spaces is a long-observed phenomenon, albeit one amplified by today’s online spaces. With the availability of social media, Internet users have more access than ever to different communities — the same access that catapults niche terms like “sigma” (from the “manosphere”) to mainstream brain rot status. Members of an outgroup can easily stumble across ingroup lingo online that they’ve never heard of; intrigued, they may begin to adopt the new terms. This occurs somewhat naturally as different social groups, each with their own linguistic strains, grow and mingle.

“Slang can start out in an almost coded way, with people trying to talk about a topic in a way that another member of their ingroup might understand but won’t be noticed by the mainstream population,” Bax said. “Over time, people in those subcommunities end up interacting with other people outside them, and those words tend to spread through social networks. With the advent of social media, this pipeline has fundamentally transformed.”

For example, the show “Rupaul’s Drag Race” introduced the language of ballroom culture, black- and Latino-dominated cradles of queer performance and self-expression, to a mainstream audience. Black Twitter spaces have influenced the proliferation of African American Vernacular English — a dialect spoken in the black community — across social media. Due to this considerable online presence, AAVE phrases like “period,” “tweak out” or “tuff” are sometimes seen as part of brain rot, or simply general Internet slang.

“I usually see slang start from comment sections underneath videos,” junior Kelly Wu said. “Sometimes I’ll see people asking, ‘What does that mean?’ and then it’s explained in a reply. I’m guessing people will go on to other videos and start saying the same thing on other platforms, like TikTok, Instagram or YouTube Shorts.”

While this process of acquisition and fusion increases linguistic diversity within mainstream lingo, it can have the opposite effect on the original marginalized ingroups. Outgroup members who adopt new vocabulary lack natural fluency in their communities of origin, which can prevent them from picking up on significant contexts and connotations. As a result, widespread usage tends to strip these words of their cultural status as identity tags, a phenomenon known as indexical bleaching.

“I think this process often goes unnoticed because it just starts happening,” Wu said. “The more that people say a slang term, the more it becomes included in the general culture. At that point, it’s not specific to the original community anymore.”

Though their colloquial nature may seem to imply superficiality, everyday slang’s meanings and origins are often charged with the rich cultural histories of the marginalized groups that created them.