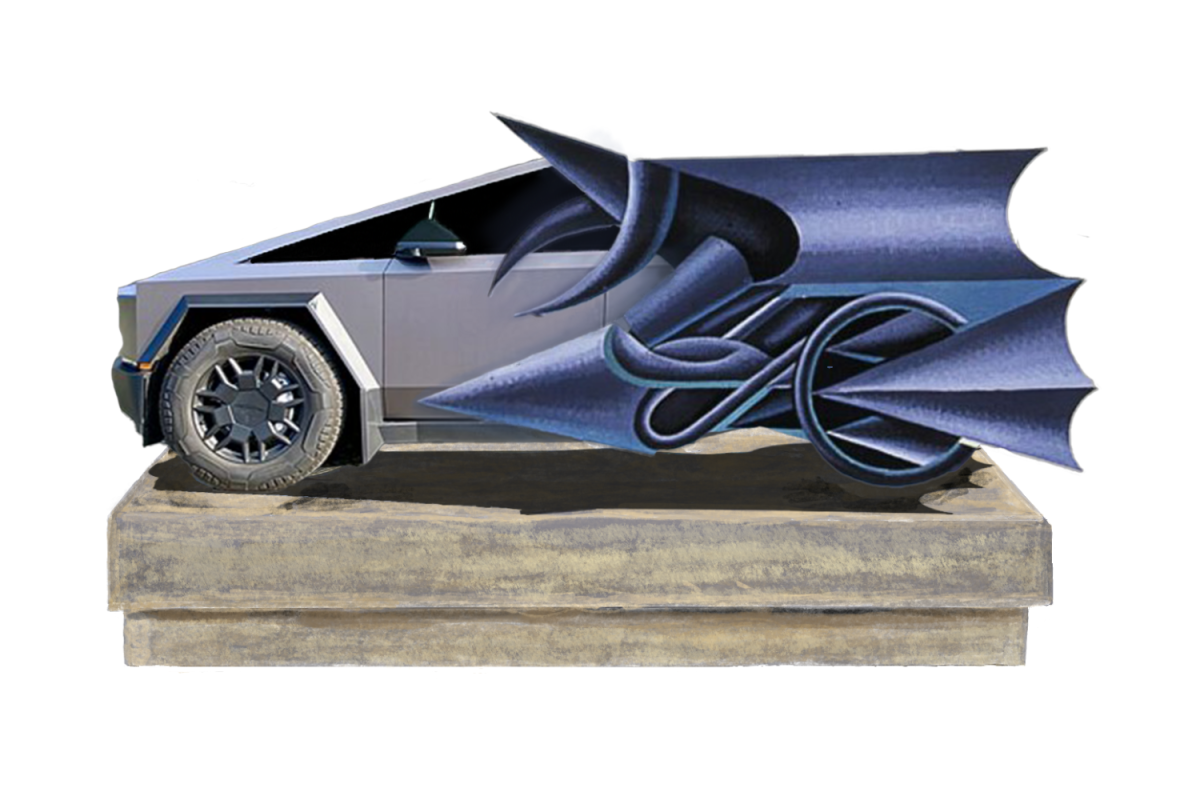

In November 2023, for the second time, Elon Musk unveiled a new model of Tesla’s long-awaited Cybertruck, flaunting the design that was intended to aesthetically capture the quality of its speed and tough skin, saying, “Finally, the future will look like the future.”

The visual appeal of the electric truck and modern tech leaders’ reverence for speed, strength, disruption and innovation encapsulates a future envisioned by Italian poets and artists in the early 20th century.

The Futurism movement, led by Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, started in 1909 with the publication of the “Futurist Manifesto,” a radical cultural movement that glorified the ideals of speed, technology, machinery, war and progress and advocated for a rejection of history and the aesthetics of the past. The main message of this manifesto claims “the magnificence of the world has been enriched with a new beauty: the beauty of speed… a roaring automobile, which seems to run on machine gun fire, is more beautiful than the Nike of Samothrace.”

Although this movement was manifested through art, literature and architecture, Fascism’s core values were intertwined with political ideologies such as fascism, a political movement which was rising to popularity at the same time. Its members championed and participated in the political upheaval of the early 1900s. Today, similar ideologies and priorities are echoed in the values and beliefs of some leaders of the modern technology industry.

“It seems that technology is allowing everyone to think less about other people and instead [focus] on advancing technology even further,” junior robotics student Suzanne Das said. “We’re becoming a lot less helpful for one another; we’re losing our touch, our relationship with [other] humans.”

Musk, for example, has influenced the tech world through companies like Tesla and SpaceX, often stating their goal as part of a vision to advance the human race. Musk’s drive to populate Mars and revolutionize transportation with electric vehicles aligns with the Futurists’ vision of technology as a tool for reshaping the future, similar to how the Futurists saw disruption as the catalyst for societal change. Like the Futurists, Musk and other Silicon Valley leaders often downplay concerns about technological innovations’ social and ethical implications and instead focus on their potential to change society.

“At the end of the day, I think we need to [put] humans first,” social studies teacher Luca Signore said. “I think that’s one of the big blind spots for Silicon Valley. We always think about the next great invention, but we don’t stop and think about whether we should make that invention. What are the benefits of it? Is it actually going to benefit us? Can we account for its consequences?”

For the Futurists, the future was interchangeable with progress, and this belief set the tone for much of the movement’s aesthetic, which idolized speed, power and innovation. Many modern day innovators share this perspective, supporting techno-optimism, believing that innovation and disorder are needed to solve the world’s challenges.

“People viewed technology as something that would save us from the horrors of the world,” Signore said. “With the advances in medicine, transportation and information, leading into World War I, people were very optimistic that all these new technologies have made the world better.”

The obsession with a renewed future came alongside a rejection of the past, as the Italian Futurist thinkers resented Italy’s legacy as the home of Roman, Renaissance and Baroque styles, a sentiment mirrored by today’s tech leaders who often preach an ignorance of historical lessons in favor of forward progress.

“The only thing that matters is the future,” Anthony Levandowski, co-founder of Waymo, a company that develops self-driving cars, said in an interview with the New Yorker. “I don’t even know why we study history. It’s entertaining, I guess — the dinosaurs and the Neanderthals and the Industrial Revolution, and stuff like that. But what already happened doesn’t really matter. You don’t need to know that history to build on what they made. In technology, all that matters is tomorrow.”

Similarly, Umberto Boccioni, a leading Futurist artist, portrayed speed and industrial progress in his pieces. For Boccioni and others who shared the same views, the rejection of tradition was seen as the crucial step to moving on from the past and embracing the new technological age of society. The Futurists’ focus on speed and progress created a clear vision of the future where forward-thinking was the only thing that mattered for societal progress, which made the past seem irrelevant.

Unlike Levandowski, some prominent tech figures have maintained a fascination with certain fragments of history. However, this fascination stems from their fixation on certain aspects of history they wish to imitate in modern-day society for profit.

“I don’t think that a lot of technologists are learning from history,” said Dr. Ryan Skinnell, a professor at San José State and author of several books on rhetoric. “Maybe some are, but they’re just very selective about what history they’re willing to learn. Zuckerberg, for example, is a big Rome guy. He loves to talk about Rome. He talks about how if we could get technology to work the way that we want it to work, we could usher in a new Pax Romana. Zuckerberg never talks about the fact that the Pax Romana required all sorts of war and violence. He just ignores parts of [history] that don’t align with value. I think the same is true of Musk.”

The history that these tech moguls choose to ignore could warn them from following the same path as the Futurist movement. Unlike other influential art movements of the time such as Cubism, Expressionism and Art Nouveau, Futurism remains largely ignored in the modern day. Even those who express the same beliefs remain distanced from the movement due to the stigma that comes with its close ties to fascism. Futurist thinkers publicly voiced their support for fascism — a political movement that aggressively embraced nationalism, authoritarianism and modernism.

Just as Marinetti wanted to reform Italy through a disruptive, technological lens, Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini advocated reforming Italy through an authoritarian lens. Both ideologies paradoxically aimed to restore Italy to its former glory while reshaping the country in the image of militarism and modernity.

“Both [the Futurist and Fascist] movements are rooted in disgust,” Dr. Skinnell said. “They thought in terms of the beauty and the sublime and if we could just get the best of everything, then we can wipe away all that poverty and disease [happening at the time.] If you listen to them talk and read the things that they write over and over and over again, sort of underneath all of it is this disgust [for the old ways of doing things.]”

Both movements rejected the past by glorifying the future and wanted to break free from traditional norms and social structures. Fascist leaders aimed to push their countries forward through radical social and economic policies that often disregarded individual rights in favor of national unity and strength, while Futurist ideologies preached the breaking of artistical norms as the only acceptable way of making art.

The Futurists’ association with fascism and their focus on progress without considering the past offers a cautionary example. Modern tech leaders, like their Futurist predecessors, prioritize technological advancement, but the historical context of such movements suggests the importance of considering ethical implications alongside progress.

Dave Blakesley • Aug 30, 2025 at 4:02 pm

I’m directing a dissertation on “Techno-Optimism” and rhetoric at Clemson and found your essay illuminating! Well done. The Futurist movement is re-emerging these days, with similarly sinister influences and influencers on the political side.