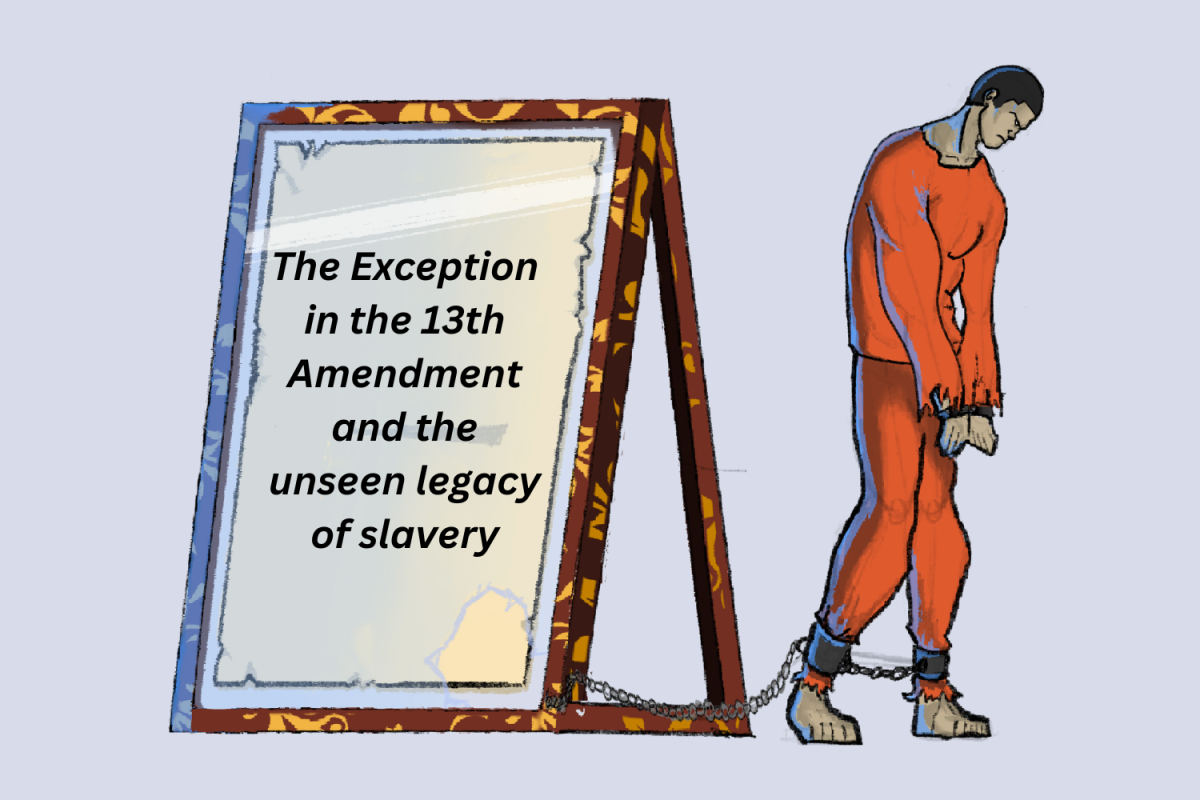

Beneath the heat of a relentless Southern sun, shackled hands work tirelessly in the fields; backs straining against the weight and echoes of slavery in the modern day. The Thirteenth Amendment is often seen as a law that completely abolished slavery, yet a loophole remains: allowing slavery to remain legal as a form of punishment. In November, California will vote on Proposition 6 — a measure that would remove this exception from the state constitution. California is one of 16 states where the constitution’s wording remains.

Written in 1864, the 13th Amendment outlawed all forms of slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” The Amendment excludes labor protections for incarcerated workers, including workplace safety regulations and minimum wage. Many believe the loophole served as a way to convince officials from both the North and South to support the amendment, drawing language from similar slavery documents at that time, such as the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

“I think the intention of the amendment was basically, ‘we need labor and we also need to control black people,’” said Libra Hilde, Chair of San Jose State University’s History Department. “They didn’t like emancipation and didn’t like the end of slavery, so they needed external control to keep black people at the bottom of the social ladder, and the way to do that was through the justice system.”

Chattel slavery, a system in which individuals were permanently owned as property, was a race-based form of slavery that became extremely common in the Americas after European colonization. Enslaved Africans were transported across the Atlantic and sold to meet the demands of colonizers, who had seen a sharp decline in their Indigenous labor forces. Chattel slavery is distinct from other forms of slavery because chattel slaves and their children had no means of escaping the system. This form of slavery was almost exclusively applied to Africans.

Even though slavery became a more prominent feature in American economics by providing necessary labor for the agricultural industry, support for the abolishment of slavery through political activism and advocacy eventually overpowered the dissent. Yet, the institutional struggle against forced labor continues in the 21st century as the prison industrial complex perpetuates a form of modern-day slavery through inmate labor.

In addition to free prison labor, the loophole laid the groundwork for exploitative systems like Black codes and convict leasing in the 1860s. Black Codes criminalized actions like “rude gestures” or “mischief” and were used to target African Americans. The result was an overrepresentation of in Black people in the prison system, with 33.3% of the entire prison-population being Black, with only 13.6% of the overall population being black. Later, a convict-leasing market in Southern States was established, in which inmates were leased to private companies by the government. In the 1871 Supreme Court Case of Ruffin v. Commonwealth, courts ruled convict leasing to be legal and deemed those incarcerated to be equal to that of an enslaved person.

Today, the rise in prison labor reflects the same patterns. States leasing prisoners for agricultural labor has been an ongoing problem in the 20th century, providing farms with labor in the form of inmates. The monetary incentive behind mass incarceration allows the effects of Black codes to exist — even in the modern day. According to a study done by the Associated Press, over $200 million dollars were amassed in the agricultural industry from prison labor alone. Inmates are used for labor-intensive farm work to grow crops like onions, apples and tomatoes. Prisoners, in some cases, receive zero compensation for their work, even though they produce roughly $11 billion annually for prison systems. In April of 2024, a lawsuit was filed against the company Aramark for not compensating their prison work-force. The California Supreme Court ultimately dismissed the case, deciding that the company was not required to compensate the workers when there are no minimum wage laws protecting the prison labor force.

In addition, inmates are often the victims of harsh work-environments, including facing exposure to harmful chemicals and extreme temperatures. Those who refuse are subjected to punishments like solitary confinement, denial of reduced sentences and more. Samual Brown, a member of the prison work-force during COVID-19, said that prisons could strip inmates of cell phone privileges, visitation rights and the power to order one’s own food during an interview with CalMatters.

“At the end of the day, it was individuals and groups of people who made the decision to weaponize the loophole and use it against formerly enslaved people,” said Michele Bertelone, American History Professor at De Anza College. “It’s a failure of the system and failure of the morals of the people involved.”

Examples of prison labor include inmates being forced to fight fires, making up 30% of all wildfire fighting forces in California, creating back-to-school furniture and agricultural labor — paralleling chattel slaves who predominantly worked on farms. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, inmates are paid 12 to 40 cents per hour for a single assignment. Despite the low wage, a significant portion is still taken and used to fund the country’s Criminal Justice System, preventing inmates from saving up any substantial amount of money.

A more notable aspect of prison labor is the involvement of mainstream corporations. Companies like Amazon, Home Depot andFedEx all use forced prison labor; many popular food brands have been found to use prison labor to make products as well. Inmates are actively involved in making every-day goods, highlighting the far reach of the prison-industrial complex.

“Now, for-profit companies are getting paid by the government to manage much of the prison system, and those companies are also, to some degree, able to benefit from prison labor,” Bertelone said. “Here, we can see the intersection between commerce and the penal system.”

In 1971, The Attica Correctional Facility in New York was taken over by prisoners, who demanded the right to form a union and minimum wage payment. Although the city did agree to meet some of their demands, such as providing access to higher education and religious freedom, their call for increased wages were not met. More recently, prison-laborers across the country protested in 2018, calling the prison system ‘modern-day-slavery’. Deemed the largest strike in U.S. history, prisoners made a list of ten demands including voting rights and removal of free prison labor. None of the demands were met and prisoners were punished through prison transfers and solitary confinement.

Beyond the issue of prison labor, the challenge of recidivism remains. Recidivism, the tendency of a previously incarcerated person to continue committing crimes even after release, continues to fuel debates over how effective rehabilitation in prison systems truly is.

“Most citizens and politicians want to see a rehabilitation system in prisons,” social studies teacher Jeffrey Bale said. ”They aren’t comfortable with having prisoners do whatever they want. They sometimes tend to support systems in which prisoners work for their crimes. But that begs the question, why can’t we be like Japan, who has a recidivism rate in the single digits?”

As a response to this issue, Proposition 6 has been put on the California ballot and will be voted on in November. Voting yes on the measure would ban involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime, while also preventing the state from retaliating against those who refuse to participate in labor.

Proposition 6 was originally not passed when put on the ballot in 2022, but Assemblymember Lori Wilson resparked the debate for Proposition 6 as one of 14 bills designed to advance reparations for descendants of enslaved people in America.

The proposition has gained near unanimous support from majority liberal advocates. Proposition 6 has since gained $814,000 in support from human rights organizations, individual donors, political action committees and others. Proposition 6 has received no formal opposition, however, several newspaper editorial boards have published articles arguing against this issue. However, a recent survey done by the Public Policy Institute of California states that only 46% of voters said they would vote yes on the proposition. In a statement made to the Sacramento Bee, PPIC survey director Mark Baldassare said it was due to lack of awareness on what the measure would actually accomplish.

“In the past few decades, there’s been this rediscovery of America’s racial inequality issue,” History Club Co-President Isaiah Sit said. “People are becoming more and more aware that these ideas of racism and injustice are still around. Now, a lot of people are using that awareness to try and fight against it.”