NASA’s cancelled all-female spacewalk: persisting gender inequality in STEM

Out of stock: lack of NASA spacesuit sizes highlights gender inequality in STEM

April 29, 2019

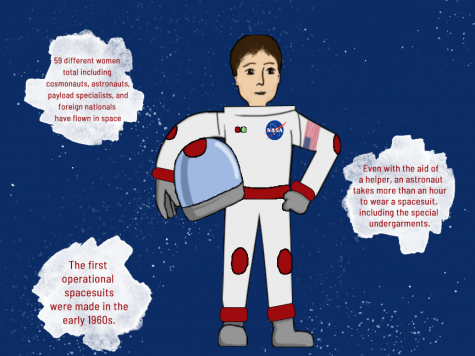

Imagine being one of the two women set to participate in the first all-female spacewalk. Then, imagine being told that only one woman would be able to go — the other would be replaced by a male astronaut. As astronauts Christina Koch and Anne McClain geared up for the first all-female spacewalk, set to take place on March 29, McClain changed her mind about her spacesuit size — she had previously said that either a medium or large spacesuit would work, but later decided that she only felt comfortable wearing a medium for the spacewalk. NASA could only prepare one medium spacesuit, which was worn by Koch, so male astronaut Nick Hague replaced McClain, who participated in another spacewalk, along with a different male astronaut.

As someone who has always been interested in STEM, I was shocked that NASA did not have more than one medium spacesuit, the typical size worn by female astronauts, who are usually of smaller stature. I couldn’t believe that NASA, an organization that has sent more than 300 astronauts into space and conducted more than 200 spacewalks at the International Space Station, could possibly lack resources for female astronauts. Though initially surprised, I soon realized that such incidents are horrifyingly commonplace in today’s supposedly progressive society, and even in my own life. The fight for gender equality is far from over, particularly in STEM fields.

Even though McClain had originally said that she could wear either a medium or a large spacesuit, NASA’s lack of medium spacesuits leads me to wonder whether the organization assumed that women would not need spacesuits because they would not be astronauts in the first place.

The exclusivity of STEM fields discourages girls from pursuing their passion in STEM. A study conducted by Microsoft in partnership with KRC Research in 2018 showed that girls lose interest in STEM as they get older, as their confidence in their STEM skills wanes. The same study showed that inclusivity and having female role models are key to encouraging girls to continue exploring STEM.

In my attempts to pursue science or engineering activities, I’ve felt that lack of confidence highlighted in the study. Entering freshman year of high school, I was super excited to join the robotics team, imagining how I would spend the next four years as part of a tight-knit group, tinkering with robot parts and writing code to make the robot function. At the end of that school year, however, I was incredibly discouraged. After attending confusing workshops and build sessions where I didn’t have a major role, and seeing male members of the team working on parts of the supposedly “All-Girls” Subsystem, I felt that I didn’t fit in, thinking I could never actually contribute to the team.

A year later, I attended the California State Summer School for Mathematics and Science. For the final project, I originally had a group comprised completely of girls, but the professor made our group split up, saying that she would not have the project be girls versus boys, and three of the girls and I ended up on a team with two boys. I felt discouraged yet again. Always watching over our work, the boys didn’t trust us to complete even the simplest of tasks. I had initially wanted to work more on the software and electrical aspects of the project, but the three other girls and I were instead relegated to working on the mechanical side, with the boys taking on the software and electrical work. When we had finished the mechanical work, us girls attempted to offer help to the boys, but our repeated offers were refused. Our professor remarked that she was disappointed that we were sitting idly as the boys worked — a remark that drove me to tears — but did not make the effort to fully comprehend the situation.

It was only when I attended the Summer Science Program (SSP) in Astrophysics last summer that I finally felt truly supported in the STEM community. SSP made an effort to arrive at gender equality by having equal numbers of girls and boys at the session and guiding all students in a supportive manner. Finding myself in a collaborative community where gender did not matter, I was free to do what I wanted: control the computer to position a telescope, code in Python to determine my asteroid’s orbit and write up a final report. I remember arriving at the observatory with my team of three — my other two teammates being boys — and declaring that I wanted to take on the role of controlling the computer; no one stopped me. Unlike my previous experiences with STEM, SSP encouraged my interest in those fields. I firmly believe that we need more efforts like those of SSP to ensure equality and encouragement for women in STEM.

Even the smallest steps can make a difference. Whether it is a father guiding his daughter in completing simple arithmetic, a teacher complimenting a young girl on her coding skills or a college professor encouraging a female student to participate in a summer research opportunity, all members of our community can work toward making women feel like they belong in STEM.

Although the media may have exaggerated the exact situation, which was also partly due to McClain’s change in personal preference, NASA should have had more medium spacesuits available in the first place; spacesuits should also be made to fit women, not only men. If we begin to tackle the problem of the lack of women in STEM more seriously, we can ensure that one day, medium spacesuits will be the norm as well, and we can, at last, have our first all-female spacewalk.