White picket fences, suburban homes and a nuclear family unit — the traditional image of middle-class America. Not only is this image not representative of all middle-class Americans, but the comfortable and stereotypical view of the average middle-class American has increasingly diminished in the Bay Area, due to issues such as inflation and growing financial insecurity, distancing many citizens from the “middle class” group.

In the United States, the middle class is measured by household income. According to the Pew Research Center, households that earn between two-thirds and two times the median U.S. household income are considered to be a part of the middle class. In the Bay Area, families who make up the middle income earn anywhere from $77k and $232K annually. Despite these numbers, societal perceptions of what it means to be a part of the middle class has changed based on the shifts in the global economy.

“Starting in the 1970s, the impact of globalization and technological change has resulted in the benefits of economic growth going to a much smaller number of people,” Government and Economics teacher David Pugh said.

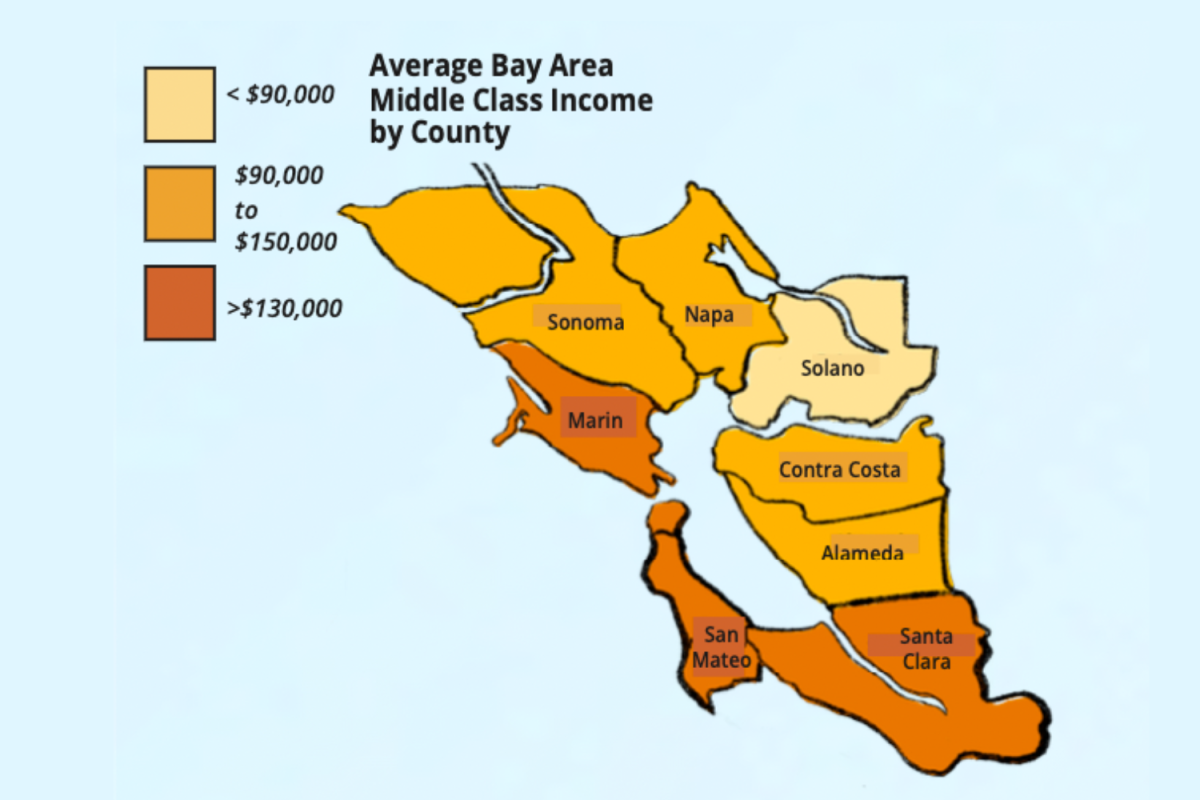

In the Bay Area, the income threshold for middle class households is among the highest in the country. Three out of the top five cities nationally with the highest middle class income threshold are located in the San Francisco Bay Area. Residents in Fremont, San Jose and San Francisco need to make upwards of approximately $104,499, $84,673, and $81,623 respectively in order to be considered a part of the middle class.

In recent years, the gap between the upper, middle and lower classes has widened. This can be attributed to household incomes growing significantly within the upper classes whereas middle class income growth has stagnated. Such phenomena can especially be observed in California where families in the upper class made 11 times more salary than those in lower classes, as stated by the Public Policy institute of California. In fact, the wealth distribution within the state is notably unbalanced as 20% of all net worth is concentrated in the 30 wealthiest zip codes, which is home to only 2% of California residents.

With surging prices in recent years, the Bay Area middle class has shrunk in size. Many middle class families report their earnings are falling behind the cost of living. As a result, California lost nearly 7% of its middle-income population while the low and high income populations increased by 37% and 34%, respectively, between 2000 and 2019. Due to increased expenses for goods and services including food, transportation and healthcare, families are finding it challenging to cover the rising costs of living. The San Francisco Chronicle finds that inflation has meant that Bay Area residents are spending $4,400 more annually on goods and services.

Housing has become a struggle for those who contend with the high costs of living which can be a product of issues like gentrification, where higher earners inhabit traditionally lower income areas. Gentrification improves housing and attracts new real estate, at the cost of sacrificing the culture and way of life of already-established communities. Spanning through the past several decades, Bay Area neighborhoods have seen an influx of high-income residents moving to previously less-expensive housing areas– namely San Francisco and Oakland. As a result, prices get marked up, displacing inhabitants. Middle class residents must move to smaller units regardless of family size, opt for longer commutes and may not have the option of home ownership.

“The high cost is associated with high salaries that tech companies are able to pay employees,” business teacher Andrea Badger said. “Unfortunately, those of us who work in service and the public sector do not get to benefit from that, but we still have to pay to live here.”

In the Bay Area, essential workers such as those who work in education, health care and professional services, must grapple with a housing stock which is oriented toward higher-earning households. Essential workers cannot just move out of their area to cheaper locations as high prices extend throughout the Bay Area. Thus, households that are within the workforce threshold are priced out of homeownership. In turn, families must turn to renting. In the Bay Area, the rates of rent are significantly higher than other regions and workforce households are disproportionately affected as they are forced to pay 30% of their incomes, which is more than other peer metropolitan regions.

“Middle class purchasing power has dropped when adjusted for inflation, whereas the income of the top 1% has increased significantly,” Pugh said.

Through the effect of rising living costs on the Bay Area’s middle class, more families are starting to fall deeper into low-income categories. Consequently, certain demographics are especially affected based on where they are concentrated in the Bay Area and their consumer habits. Region-wide trends indicate an increased disparity in income levels of different racial groups. According to a study from the Bay Area Equity Atlas, across all racial groups, there was a relatively lower percentage of middle-income residents than the percentage of residents who were on the polar ends of the income spectrum. Similar proportions of white and Asian American Pacific Island family members in the region were considered either as either very low income or very high income. However, Black and Latinx residents in the Bay Area represented a greater proportion of low-income residents and a smaller part of high-wage earners.

The middle class has also seen the largest rates of medical debt. Almost 17 million middle class families were unable to pay their medical bills in 2020. In comparison to other classes, this is roughly 1.5% higher than lower-income families and 9% higher than high-income families.

Higher education has become a crux for many middle-class Americans as tuition rates have skyrocketed while incomes may have not. In light of the changes made to the FAFSA form that was released last December due to the 2020 FAFSA simplification act, the volume of financial aid available for lower income students has grown offering more equitable prospects for underprivileged students. Middle class students who do not qualify for the same aid are expected to experience higher educational expenses with the new provisions. For instance, the new form has removed the option for aid for families with more than one child attending a university. Previously, families could divide their Expected Family Contribution equally by the number of children that were enrolled. Under the new formula, this number has been coined as the Student Aid Index and has instead become the minimum payment for each student per family.

“Everyone is affected,” Badger said. “Middle, upper and lower income families are in this same boat. The main difference is the amount of disposable income available to families.”