Green Book cruises past controversy to pick up problematic Best Picture win

April 1, 2019

Nearly 30 years after “Driving Ms. Daisy” won Best Picture at the Academy Awards, “Green Book’s” Best Picture win at the 2019 Academy Awards feels like déjà vu. When “Green Book” was first released, it was met with acclaim for its feel-good story of an interracial friendship. However, such praise does not come without controversy over the movie’s omission of the historical artifact, the Green Book, from which the movie gains its title; disputes over the historical accuracy of the screenplay; and its white savior trope that trivializes the truth about racism in the 1960s.

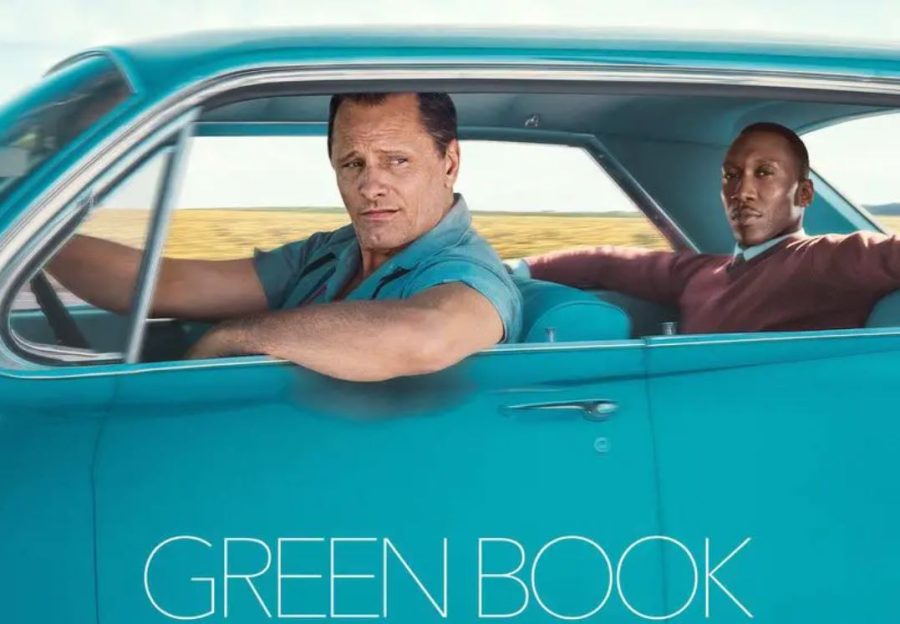

“Green Book” tells the story of Tony Vallelonga, played by Viggo Mortensen, an outgoing yet crass Italian-American from the Bronx who is hired by African-American world class pianist Dr. Don Shirley, played by Mahershala Ali, to work as his chauffeur and bodyguard during his eight-week tour through the Jim Crow South of 1962. Shirley is the polar opposite of Vallelonga: eloquent, perfectionistic and refined. Vallelonga is hesitant to work for a black man, but ultimately takes the job to support his family. Through banter with Shirley during drives and recognition of Shirley’s vulnerability beneath his sophisticated exterior, Vallelonga’s ideas of race transform, and the two form a unique friendship.

The biographical dramedy was not an immediate box-office success, but still won the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2018, earned five nominations at the 2019 Golden Globes Awards, winning Best Motion Picture-Musical or Comedy, and attained another five nominations at the 91st Academy Awards, where it took home Best Supporting Actor for Mahershala Ali’s portrayal of Dr. Don Shirley, Best Original Screenplay and Best Picture.

Still, such critical acclaim should not overshadow the myriad of controversies surrounding the film. Despite the movie being titled “Green Book,” the actual Green Book itself lacks prominence in the film. Black travellers who tried to stay in a hotel or eat at a restaurant unwelcoming to colored people could have been met with potentially dangerous consequences. Victor Hugo Green, an African-American mail carrier, created the Negro Motorist Green Book that listed not only accommodations and restaurants, but rest stops, salons and beauty parlors “safe” for black travellers. In the 1960s, the South was still legally segregated and so was the rest of America, albeit informally. The movie instead conveys that the Green Book was only necessary in the Deep South, when in fact, racial hostility posed a threat anywhere in America. However, in the movie, the book makes more frequent appearances after the pair crosses Kentucky, and there is less police intimidation when they pass back over the Mason-Dixon line away from the South.

Vallelonga only fleetingly explains the Green Book’s purpose, to list lodging and dining that serve black travellers, but otherwise, the book is not acknowledged by name and is only featured in several brief clips of Vallelonga flipping through it, or the book seated on the passenger seat beside him. Given the film’s title, one would expect “Green Book” to delve into the content and context of the guide, and as a result, its measly portrayal detracts from the gravity of racism it involves.

“Green Book” is both an unfitting and diminishing title for the film, which fails both to accurately depict and adequately represent the Green Book. But the very existence of the Negro Motorist Green Book stood for years of racism and both legalized and unspoken segregation, and titling the movie after the book allows the audience to replace the prejudice behind the creation of the actual Green Book with a feel-good film and suppress its reality. The fact that the book was necessary for black travellers to simply remain safe is reflective of the belief that black people were inferior to white people and even of ongoing discrimination today. For an upbeat dramedy to be named after this painful part of a far too recent history deeply diminishes and even makes a mockery of the artifact.

While any film “based on a true story” does not guarantee absolute adherence to the true events, one of the lead writers for Green Book was Tony Vallelonga’s son, Nick Vallelonga, which boosted credibility. While Tony’s side of the story was well-sourced, Shirley’s family spoke out against the film’s portrayal of Shirley after the movie’s release. Shirley’s brother, Maurice, in particular, sent a strongly worded message to various media sources, alleging that Shirley and Vallelonga were never friends, and that Shirley maintained a strictly employer-employee relationship with Vallelonga. Maurice also refuted the movie’s depiction of Shirley as cut-off from his family, insisting that the two spoke and wrote to one another frequently. One part of the movie plays on the racial stereotype associating black people with fried chicken, with the film version of Shirley claiming he had never had fried chicken before, and Vallelonga teaching him how to eat it. Maurice, however, disputed this story, stating that Shirley not only had eaten fried chicken in the past, but would never allow a white man to pressure him into eating it. The Shirley family has boycotted the film due to the film’s inaccuracies creating a depiction of a fantasy rather than reality.

It is no surprise that even films inspired by true events are required to take some creative liberties, especially when the main characters have passed. However, it is disturbing how much of Shirley’s character is constructed from pure imagination, especially his purported ignorance of black culture. While it may be true that Shirley was not nearly as integrated with the black community due to his profession and fame, all black performers at the time, including Nat King Cole and Shirley himself, faced rejection, discrimination and even violence in their careers. To rewrite Shirley’s narrative, in spite of such incidents and what life was like as a black man in America in 1962, regardless of status, is an erasure and reinvention of his identity. Such is particularly problematic for a team of white scriptwriters to do. Though the story is told through Vallelonga’s lens, the uniqueness of the movie truly lies in Shirley, and for his character to be fabricated is careless and disrespectful.

Still, the fact that the story is even told from Vallelonga’s perspective is the essence of the problem with Green Book. Hollywood has historically made films, such as “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “The Blind Side” and “Hidden Figures” that include non-white narratives, using white characters as liaisons for the story. Even when the person of color is the one who makes the script a story, the end product is a white savior film in which the person of color’s role is pushed aside for the white character to take the lead, and ultimately racial issues are belittled or blatantly misportrayed.

As Vallelonga escorts Shirley on his tour through the South, on numerous occasions, Shirley finds himself in a dangerous situation, usually as consequence of his race, and Vallelonga heroically saves him. The film, which intends illustrate an interracial friendship, instead ends up depicting a black man desperately in need of a white man to pull him out a trouble with the authority of his race alone. Vallelonga warns Shirley not to count his money in a black public space. Vallelonga shoots a gun to scare away thieves who try to steal from Shirley’s car. Vallelonga intervenes when white men nearly kill Shirley at a bar. Vallelonga helps Shirley evade jail time for a sexual encounter with a white man at the YMCA. Time after time, Shirley is helpless, and Vallelonga is powerful.

Vallelonga also educates Shirley about black culture, playing well-known African American singers, such as Little Richard and Aretha Franklin’s, music for him, and introducing him to fried chicken, which Vallelonga is shocked by since to him, fried chicken is “[Shirley’s] people’s” food. While it is clear that Vallelonga’s stereotypical understanding of black culture is intentionally comical, when Vallelonga encourages Shirley to play jazz music at a black restaurant, as opposed to his typical tour stops playing classical piano in venues with white audiences, it appears that Vallelonga even serves as an agent for Shirley to reconnect with black culture. “Green Book” is not the story of two men of different races coming together to find themselves as equals; rather, it perpetuates the idea that no matter the efforts of a black man to compensate for and grow beyond entrenched stereotypes about his race, the white man can get away with any shortcomings and still reign superior.

The decision to pick “Green Book” as Best Picture was a clear attempt by the Academy to prove its acceptance of diversity and inclusion of non-white narratives into the film space. “Green Book,” is a feel-good movie, because it makes the audience believe that since today’s racism is not quite as extreme as that depicted in the movie, racism is for the most part gone today, simply because we’re not nearly “as bad” as before. But fellow Best Picture nominee Spike Lee’s BlacKKKlansman which interweaves clips from both the 1970s and present-day to show that the two are frighteningly similar, proves that there is still a large part of America that still reinforces the racism portrayed in “Green Book.” Lee himself was openly upset about “Green Book’s” win; in reference to his loss in 1990 for Best Screenplay with his film “Do the Right Thing” to “Driving Miss Daisy,” Lee told reporters “Every time someone’s driving somebody, I lose.” Lee was seen waving his hands in anger before attempting to leave the theater after “Green Book” was announced as the Best Picture winner. He later commented on the win, saying “I thought I was courtside at the Garden and the ref[eree] made a bad call.”

Though it is true that BlacKKKlansman and Black Panther’s nominations were paramount achievements, “Green Book’s” Best Picture win at the Oscars reveals that the film industry is far from making the necessary strides for diversity and is still willing to encourage and reinforce outdated stories about people of color.