Preventing food waste with fresh solutions

Graphic Illustration by Jonathan Ye

December 12, 2018

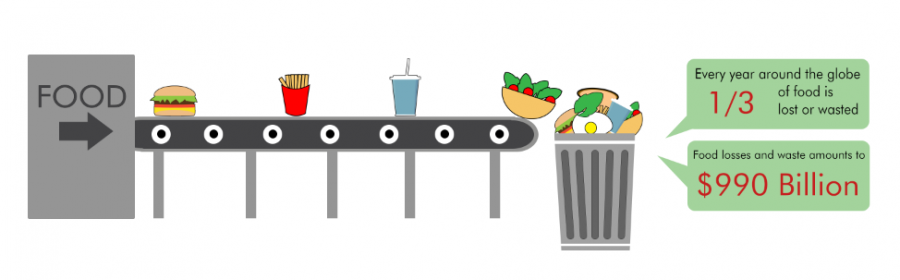

Californians throw away six million tons of food each year, according to Sacramento-based CalRecycle, yet one in six Bay Area residents is unable to access a sufficient amount of affordable and nutritious food, as reported by the Joint Venture Institute for Regional Studies. So what impact does food waste have, and how can producers and consumers prevent it?

The impact of all this globally wasted food is surprising: increased greenhouse gases caused by the decomposition of organic matter. When compared with the total emissions from all countries, global food wastage emits the third largest amount of greenhouse gases in the world, in terms of gigatonnes of equivalent carbon dioxide, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. The FAO also reports that the immense carbon footprint of food wastage contributes to global warming, since its emissions are almost equivalent to global road transport emissions. Leftover food thrown from customers’ plates and restaurant kitchens have a substantial impact on the environment, which can be reduced by putting leftover food to good use.

At Lynbrook, approximately 400 students purchase food from the snack shack during brunch and lunch each day. Around 15 food items are leftover daily, according to food service manager Jason Senior. Santa Clara County health guidelines require prepared food to be thrown out after seven days; however, the school curtails it to only one day. The school minimizes its food waste by reusing leftovers.

“[We do not donate leftover food] simply because there is not enough,” Senior said. “Whatever is left, we will utilize somehow the following day. We made paninis out of the [leftover] meatball subs: we took them apart, added some produce and cheese and grilled them. We try to change it as much as possible so it doesn’t look exactly like the leftovers. If we have chicken from a salad, we’ll pull the chicken out and we’ll make a wrap out of it or a sandwich.”

In addition to recycling food, the cafeteria limits food waste by carefully planning out the amount of food ordered each week, even studying past records of the number of students buying lunch daily to assist in his planning.

“I just pulled reports from last year, and I estimate about a 20 percent decrease in student participation [from last year],” Senior said. “Now I actually have records from August up to today that I can look back on, and that’s how I’ve come up with a number [for the amount of food to order], and then I add a little bit of cushion just in case.”

Although reusing leftover food is a great way to reduce food wastage for the school cafeteria, it does not work as well for larger chain restaurants such as Go Fish Poke Bar on De Anza Blvd. Go Fish, an over-the-counter style fish salad bar, is committed to using fresh food in its dishes to reduce storing ingredients, mainly fish, for too long. Go Fish reuses leftover food, but in a different manner.

“We don’t like keeping fish overnight,” said Go Fish De Anza Manager Jaden Sisang. “Even though it’s frozen, we like getting a fresh shipment every morning. For salmon and tuna, it’s okay for us to keep it for a couple days. But for fish like the yellowtail, which browns easily and oxidizes, we have to wrap it extra tight and make sure it’s air sealed to increase its longevity and shelf life.”

Since raw fish cannot be stored for too long, the restaurant chooses to deal with leftovers in a unique way: offering the leftover food to nearby Go Fish stores, as well as its own employees.

“We’re closed on Mondays,” said Go Fish De Anza Manager Momo Nguyen, “But we also have three other locations, which is kind of cool, because they’re not closed on the days that we’re closed. So, we just send [leftover food]over to them and in any case, our employees end up buying whatever is left over for much cheaper [compared to what our customers pay].”

Due to the longevity of their ingredients, including salt, tamari, serranos and green onions, Go Fish ends up throwing away a mere pound per month of the toppings that have spoiled and 10 to 15 pounds of the unusable parts of the fish, like the skin, bones and head.

To Shriya Reddy, a senior who works at Boudin SF on Stevens Creek Blvd, customers do their fair share in preventing food waste. However, one of Boudin’s signature soup add-ons, the bread bowl, is one of the food items that people tend to throw away.

“Usually I find that it’s more napkins than food left on plates that’s thrown away,” Reddy said. “I almost never throw out sandwiches or salad because either people finish it or they take it to-go. When it comes to bread bowls, a lot people order them with their soup, but they leave a lot of it behind. They tend to eat insides of the bread and the separated piece with their soup, but leave the crust of the bowl behind.”

Similar to Boudin SF, Rio Adobe is a traditional dine-in restaurant that finds that encouraging the use of biodegradable food containers greatly decreases food waste. The Mexican chain restaurant is a certified Green Business by Santa Clara County, a certification which guarantees that a business takes extra measures to remain environmentally friendly, such as conserving energy and water and using non-toxic cleaning cleaners. To get certified, a business must prove that they fulfill all the requirements and be evaluated. Rio Adobe is aware of how much waste it produces and its manager Jim Cargill is always looking for ways to reduce and save resources.

“I’ve designed the menu so that there’s no waste at the end of the day,” Cargill said. “We downcook, or stop cooking vast quantities of food, and we chill it out at the end of the day, and a lot of the food that would be left over on the cooking line can be reheated and used successfully the next day.”

Cargill uses what he calls “menu engineering”: downsizing portions based on past records of food wastage and times when the restaurant is the busiest to determine how much food to prepare each day. If food is not consumed, it is thrown with all other food scraps, to-go boxes, napkins and paper bags in the compost, which are thrown out with two regular dumpsters a week instead of five dumpsters. However, Cargill prioritizes reusing or donating food over composting.

“When we do catered events and we have leftover stuff, there’s a couple of shelters downtown that we call,” Cargill said. “Unfortunately, the health department is pretty strict about that. I would never take food that I wouldn’t eat myself. I just know it’s going to go to waste and it’s a shame.”

It is difficult to eradicate food wastage completely, but measures can be taken to minimize it. The creative approaches taken by Go Poke, Boudin, Rio Adobe and even the Lynbrook cafeteria help minimize food waste and its impact on our society.