Minorities … can be racist too?

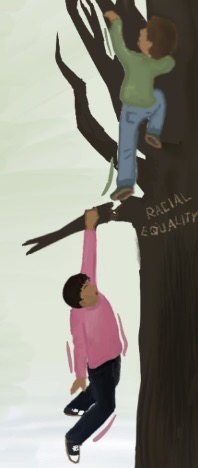

Graphic illustration by Eileen Zhu

The climb towards racial equality is overshadowed by inter-minority racism and infighting.

March 10, 2023

The evening news crackles in the background as a family eats their dinner. Is it another mass shooting? A brutal police killing of a minority? An uncomfortable conversation ensues; the father, a first generation immigrant from China, comments on the death of another black man at the hands of police with lingering indifference — not because he doesn’t care about the death, but he struggles to find an explanation for his indifference when prompted by his children, ultimately blaming the victim’s substance use as the cause of the event.

Policing has always been predicated on white supremacy, from slave patrols to oppressing African American protests in the Jim Crow South and the War on Drugs. Asian Americans, and other minority groups have also been complicit and active participants in systems of oppression and white supremacy against African Americans.

For instance, when videos of George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police officer Derrek Chauvin surfaced for the first time in 2020, many were quick to point toward the other three officers who stood by idly as Chauvin held his knee on Floyd’s neck for nine, arduous, painful minutes, one of whom was 36 year-old Asian American officer Tou Thao. Thao’s involvement specifically highlights how even well-intentioned Asian Americans can participate in an institution that continues to disproportionately affect the lives of poor, minority communities, especially African Americans.

When African American activists voice their complaints about systems of institutional racism and lack of social mobility, conservative keyboard warriors are often the first to point to the supposed broad Asian American success story: with their hard work ethic and solid traditional two parent homes, Asian Americans have escaped poverty and achieved the elusive American dream. The same conservatives were also responsible for racist rhetoric during the COVID-19 pandemic that led to nationwide anti-Asian hate crimes. A simple Google search will find that Asian Americans aren’t the monolithic group that conservatives have painted them to be: according to a 2017 American Community survey, Tongan Americans have a staggering poverty rate of 19.30% whereas Asian Indians only had a 4.40% rate of poverty.

“There is an undercurrent in East Asian American communities that despite being discriminated against in the past we still managed to become extremely successful” freshman Steven Hong said. “I feel like many point towards the supposed Asian American success then back to these ‘other’ people that aren’t as successful and look down on them.”

The model minority myth has been used to drive a racial wedge — if Asian Americans, who have faced their own fair share of discrimination, can succeed, then two centuries of systematic discrimination against African Americans can be overcomed with simple family values and a strong work ethic. Then clearly, it is not the fault of institutionalized discrimination but merely reduced to the failures of the individual to find their own means of success. This narrative not only fails to recognize the historical plight of African Americans as well as Asian Americans, it also serves as effective political rhetoric to relieve white conservatives of any responsibility to fix the system that their ancestors created in the first place.

“Because of the model minority stereotype placed on Asian Americans, they were held to this high standard in popular culture or educational places and workforces,” English teacher Joanna Chan said. “Over time, African Americans were wrongfully told ‘Why can’t you be more like this group of Asian Americans in this model minority stereotype?’ — this created a rift between both groups.”

Many on the political right have also employed a similar playbook in their approach to dismantling affirmative action in college admissions: weaponizing anger from high-achieving Asian American communities to wage an all out legal-war against an approach to admissions that aims to help lift historically disadvantaged groups into higher education, including Asian Americans. Despite this, Edward Blum, a conservative legal strategist, and president of Students for Fair Admissions, a group that aims to eliminate ethnicity entirely from college admission, sued Harvard in 2014 on the basis that their admissions had racial quotas, and created a website specifically aimed at finding willing Asian American plaintiffs and succeeded in finding them.

“There’s major pushback against the passage of affirmative action policies in general because in a way, it can promote further marginalization of minority groups like Asian Americans, but opposing such measures somewhat ignores the struggles of Black Americans,” senior Avni Mangla said.

One could argue that affirmative action, despite all its merits, still may not be the most effective way to help lift up disadvantaged communities. However, it is not an excuse to completely disregard reality: that something needs to be done to address gross racial inequalities. If affirmative action is not the answer, inaction or actively working to dismantle support systems is still unexcusable.

Though some struggles of African American communities are sometimes undermined by misguided Asian Americans, that is not to say that Asian Americans communities experience the same privileges as many white communities — Asian American discrimination is rooted deeply in American and Californian history, like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 or Japanese Internment during WW2. Systemic influences such as the model minority myth, into which many Asian American communities have unintentionally fed, contribute to Asian American reluctance to connect with African American struggles. Although taking pride in the idea of achieving success through hard work and dedication is completely understandable, it is crucial to recognize that oftentimes, success cannot be so easily achieved for not only many Black communities that have endured centuries of continuous discrimination. This runs true for several other minority communities as well. Success in America is highly complex and depends greatly on generational circumstances.

Generational differences also play a pivotal role in how many Asian Americans view race. Older, first generation immigrants who are not necessarily assimilated fully into America’s culture, may understandably have more problematic views simply because they immigrated from countries with much more homogenized populations. However, for those more acquainted with American culture and life, namely Generation Z, there is a different story: according to Pew Research Center, Generation Z is shaping up to be the one of the most progressive and ethnically diverse generations in modern history, with about 22% of Gen Zers have at least one immigrant parent.

“I think there is a decently large disconnect between the older and younger generations’ views on racial equality,” Hong said. “Older generations seem to have more problematic views concerning race relations.”

While minorities are justified in support for their own communities, selective support may detract from the struggles of other minorities and feed into the same overarching prejudice that ultimately discriminates against all minorities within America as a whole. Given that several other minority groups experience various forms of discrimination, it is increasingly troubling to see discord among communities and their stances. Experiences and perspectives greatly differ among minorities depending on their exposure to American life and culture, and no two minority groups can be grouped together simply for being discriminated against. Yet as our nation continues to be clouded by prejudice, it is more urgent than ever before for communities to understand the complexity of generational discrimination and approach unfamiliar cultures with open minds.

“We have to find our common experiences,” Chan said. “Especially due to events that lead to movements like Black Lives Matter, and recurring violence against Asians, there have been more attempts to cross barriers to help recognize close groups that have been oppressed and violently attacked just based on who they are. Recognition, if people are willing to support and help each other across racial lines, can lead to more change that would benefit all groups.”