When words cut: verbal abuse at Lynbrook

The devastating consequences of hurtful words

March 29, 2018

Junior Katherine Patel* knows the impact words have. For the past few years, she’s felt the effects of verbal abuse: low self-esteem, self-doubt and loss of trust. One year ago, Patel’s friend told her something so hurtful that it has remained etched in her memories to this day.

“A friend called me a slut and told me that others viewed her as a slut because she hung out with me,” said Patel. “That sticks with me because it hurt so much. For some time, comments like these made me believe that I was nothing but the person others thought I was. I saw myself as no more than ‘just that girl.’”

In her daily life, it was the words not directed at her, but about her, that made her afraid to go to school. Patel remembers sitting in class as she heard people around her talking behind her back about her past mistakes, feeling powerless. At school, she purposely avoided the people who had said hurtful words to her and damaged the way she felt about herself.

“There must be a reason why so many people are talking sh*t about you,” said Patel. “And when you don’t know the reason why, it really hurts your confidence. At that time in my life, I was at a place where I wasn’t doing well and I wanted to better myself, but it’s hard trying to improve when people are passing judgement and rumors about you.”

Although school does not always feel like a safe place for her, she knows that she continues to attend in order to learn. She has found a new group of friends who respect her for who she is and has slowly begun to rebuild her self-confidence. Some wounds, however, can never be healed; Patel is much quieter and less trusting than before.

“At Lynbrook, I feel that my past reputation still follows me,” said Patel. “But I know that the person I am today would not have done the things I’ve done in the past. I’ve matured and become a more empathetic person.”

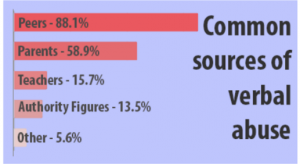

Patel is one of many Lynbrook students who have felt insecure because of what peers have said to them or made them feel. One of the most prominent forms of verbal abuse at Lynbrook is intellectual bullying: verbal or psychological rhetoric that can make someone feel inferior due to poor academic performance. Out of 199 Lynbrook students surveyed, 103 students said that they had personal experiences with intellectual bullying and 166 students said they believe intellectual bullying is prevalent at Lynbrook.

During one of her classes, junior Martha Li* struggled to understand concepts even after studying for hours. When she raised her hand to ask a question, she would hear snickers from her classmates.

“I asked a lot of questions because that is how I learn well, but I could tell I was judged for doing so,” said Li. “I just think no one should ever have to feel that way. I feel that intellectual bullying is prevalent at Lynbrook because everyone has some sort of insecurity about themselves.”

Intellectual bullying can manifest itself in subtle ways, such as when a teacher hands back a test and the room is tense with emotion — disappointment, relief, anger and excitement — all leading up to the burning question: “What did you get?” 58 percent of students surveyed reported that this question makes them feel uncomfortable.

“I once asked a student, ‘What do you do if you get a grade that you are not proud of?’ and the student said, ‘I just go into a corner and stay quiet,’” said assistant principal Eric Wong. “To me, that’s the definition of being a victim of bullying.”

Oftentimes, however, intellectual bullying is unintentional; asking such questions has become so ingrained in Lynbrook’s culture that some students forget the effect these words may have on others. Nevertheless, as harmless as they seem, questions about academic results can be devastating for some students.

“You feel worthless, lazy and as if you are never going to succeed in life,” said senior Joe Huang.* “It’s emotionally damaging.”

Teachers also view intellectual bullying as potentially damaging to a student’s self-esteem, and many consciously make an effort to dissuade students from comparing test scores or judging each other based on quantitative academic results.

“I ask that students do not compare scores in front of me because the environment I want to set in my classroom is more positive than that,” said English teacher Terri Fill. “I want students to think about how they did on the previous assignment and how they did on the next one, and they don’t need to look at anybody else’s paper for that. I really want the feedback and the grade to be a relationship between the student and me and not between the student and their peers.”

Additionally, some students and teachers feel that academic results do not fully represent a student’s intellectual ability or talent.

“Just because someone doesn’t have the best GPA doesn’t mean they don’t work hard,” said junior Joyce Ker. “There are different factors involved. I think it’s good to try your best and not judge too much based on academic performance.”

Oftentimes verbal abuse and intellectual bullying can lead to impostor syndrome, a condition Harvard Business Review defines as “a collection of feelings of inadequacy that persist despite evident success.” School psychologist Dr. Brittany Stevens has seen cases of impostor syndrome in students increase over the years she has been at Lynbrook as students develop anxieties over grades, course load and college prospects.

“[Lynbrook] can be a place where it’s very easy to feel less than or unintelligent,” said Stevens. “I’ve seen kids insist on staying in classes they are clearly struggling with because they don’t want their peers to know they are struggling. That troubles me, because in some ways, that decision is like a self-harm choice, where people choose to stay in situations that don’t benefit them because of social pressure.”

Impostor syndrome can add a great degree of stress and anxiety to individuals since they are constantly worried about being exposed as people who are unskilled.

“Impostor syndrome is a logical fallacy, and it’s not who you really are,” said Stevens. “I wish our staff could more directly name and address that feeling with the student body. Just because someone next to you is very accomplished doesn’t mean you are any less accomplished.”

Despite the negative effects of verbal abuse and intellectual bullying, victims can eventually find strength to move forward.

“I would tell people experiencing intellectual bullying that it is never your problem,” said Li. “Just be yourself. You are here to learn. Don’t be afraid to just be who you are. It’s other people’s problem that they are so insecure about themselves that they want to put you down.”

Patel has found help through trusted friends, counselors and therapists and encourages others to do the same.

“Seriously, seriously, seriously. Go talk to your counselor. Go talk to the school therapist. Go to a friend you really, really trust. Reach out. Get help,” said Patel. “You won’t improve if you’re always feeling like you did something wrong, or that you deserve to hear any verbal abuse.”

*names kept anonymous for privacy reasons