The exploitative nature of biopics

Graphic illustration by Myles Kim

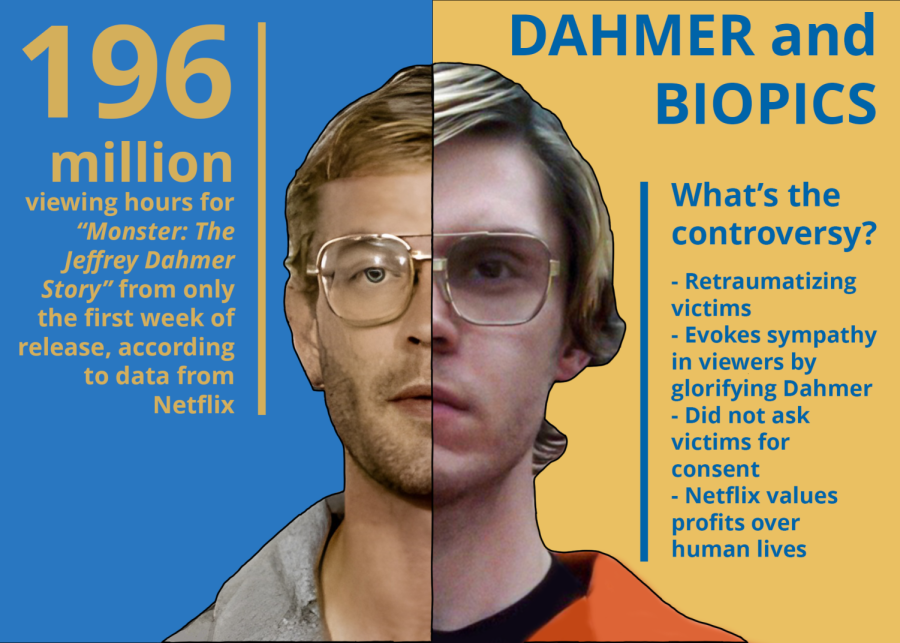

On the left, a real mugshot of Jeffrey Dahmer, on the right, his doppelganger in the new 10 episode Netflix series: “Monster”: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story which has garnered over 200 million watch hours to date. Graphic illustration by Myles Kim.

November 7, 2022

Biopics present dramatized displays of influential figures, meant to inform viewers about those who have had a significant impact on society. But how well-intentioned are these “contemporary lessons?” The answer lies in the profit-minded media.

“Dahmer”, the recent biopic covering Jeffrey Dahmer, a notorious serial killer and cannibal who brutally murdered his victims, has exploded in popularity with approximately 300 million watches on Netflix across 60 million households. Illustrating Dahmer’s tactical means of exploiting his victims, the biopic delves into specific and personal details of his life. The victims are represented as mere props to the story — Dahmer is the star. Such is the nature of many biopics: crude and overly-dramatic representations of famous figures, glorifying their lives and capitalizing on their reinvented images to turn a profit.

Many of Dahmer’s surviving victims have complained about the exploitative nature of “Dahmer” and its inaccurate depictions, which were often done without consent. The show also reminded many victims of an uncomfortable past they do not want to relive. It portrays Dahmer as an intellectual protagonist that viewers can sympathize with.

“These people lost their lives, and there’s no way to compensate them, but Netflix should at least acknowledge their significance instead of creating these one-sided mistreatments of the victims’ stories,” drama teacher Larry Wenner said.

Netflix is aware of this backlash and understands that the biopics they air will offend some people. But they continue to value profits over preserving the integrity of those portrayed, prioritizing shows that get views and shamelessly glossing over any controversy or risk that comes with them.

“I understand that a lot of these biopics are made to be interesting, but morally, directors and filmmakers have a responsibility to prioritize respect for those involved in the crime first,” junior Kaawon Kim said.

Similar patterns are seen in “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile”: serial killer Ted Bundy’s biopic, representing his murders, personal life, and even sex scenes with his potential love interest, all of which are excessive and trivialize Bundy’s actions.

Viewers have started to sympathize with Dahmer and Bundy, with users on social media platforms such as Tiktok claiming they feel sorry for Dahmer; even pining for him. Additionally, Netflix often casts popular, conventionally attractive actors and actresses to play the stars of biopics, contorting viewers’ perceptions of the serial killer. In the case of “Dahmer,” Netflix casted Evan Peters, a hotshot actor from movies such as “Deadpool 2” and “X-men: Apocalypse,” which has caused many to associate the sinister Dahmer with the likable Peters.

“If you get a famous actor to play someone evil, the audience already has a preconceived idea of liking that person,” Wenner said. “So, the media can’t accurately portray this nefarious character since the casting taints the audience’s view of what historically happened.”

Even biopics about those who positively impacted society can be misleading. For instance, “Blonde,” the biopic about Marilyn Monroe released on Aug. 20th, overly sexualizes Monroe without focusing on her many achievements in acting. It sparked controversy among models and actresses such as Emily Ratajowski, who believes the show fetishizes female pain. Many viewers also felt extremely uncomfortable watching the biopic because it included graphic scenes of abortion and sexual assault. While actress Ana De Armas portrayed Monroe very well, the plot of the movie itself glosses over Monroe’s presence in Hollywood.

Of course, biopics are enticing to streaming giants and media corporations, attracting a substantial number of annual viewers. Netflix may argue that they are merely following a protocol that turns a profit. However, Netflix has billions of dollars in revenue from countless other TV shows. Consumers should also stop valuing misleading entertainment and discourage media organizations from continuing to produce similar content.

Despite this, it is still possible to make an insightful biopic that is worth watching, if approached with respect and research. “The Imitation Game,” is a biopic about Alan Turing, the man who cracked the German Enigma during World War II, and accurately illustrates Turing’s social awkwardness and homosexuality while also representing his brilliant mind.

In the case of serial killers and murderers however, biopics are constantly at risk giving off the wrong message. Netflix and other media organizations should stick to documentaries that use consent of victims and safe forms of representation that do not negatively influence those who watch them, evoke trauma in victims and delude viewers about someone the media does not personally know.

“It would be better to get actual interviews with the serial killers or figures in a documentary to actually see their personalities, instead of them being played by someone else, so their depiction can be more accurate,” Kim said.