Thirsting for information in news deserts

October 10, 2022

Journalists are often referred to as the “Fourth Estate,” a term attributed to the infamous 1789 Estates General meeting in Paris — the catalyst for the French Revolution and an acknowledgment of their influence and status in a democratic society. However, in the modern age, the term has lost some of its edge, partially due to the increased dissemination of inflammatory news, which has perpetuated mass closures of local news publications across the country. Hence, it is increasingly difficult to find trustworthy, relevant information. An average of two or more newspapers go out of business each week, putting large areas of the U.S. at risk of becoming news deserts. The loss of credible local news not only augments the spread of disinformation and political and economic divides, but also paves the way for corrupt politicians and corporate monopolies to thrive in its absence.

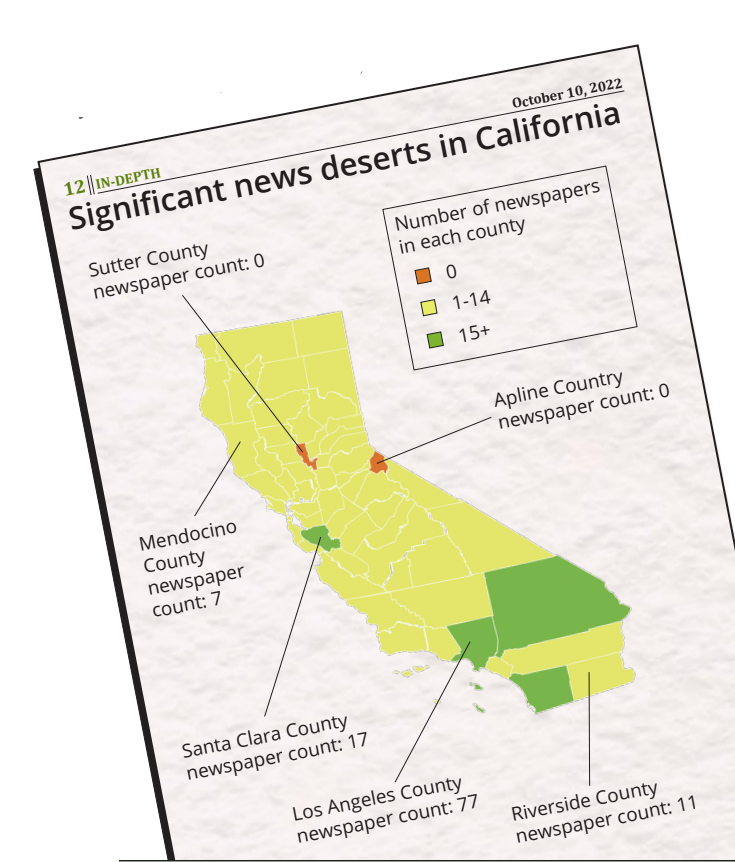

News deserts are geographical areas in which communities lack access to dependable local reporting. The term also refers to specific demographics that are ignored by the media, including typically rural and impoverished communities. Deprived of reports on regional topics, residents are left in the dark regarding present proceedings and are divested of the ability to function as fully-informed citizens.

Traditionally, local papers have been entrusted with this vital duty of acting as a voice for their communities. Scholars and journalists have documented various detrimental effects that the loss of a local publication has on a community: from decreased voter participation to increased corruption in both governments and businesses. The decline of local news indicates that not only is coverage on fundamental issues such as public safety and education vanishing, but also area-specific human-interest articles deemed too minor for larger news.

The journalism’s industry’s current business model was created in 1833, with the invention of the penny press. To this day, American journalism continues the antiquated practice of distributing the news for very cheap subscription prices and relying on advertising to finance themselves.

“The fact that the industry as a whole has not broadly changed its business model in these two centuries is contributing to the news crisis,” associate professor of journalism at University of Kansas Teri Finneman said. “Many small weekly newspapers cost one dollar a week, and that’s giving us 14 cents a day to support a business. Can you survive on 14 cents?”

In the places of vacant newsrooms, nothing but historical footnotes are filling in the news vacuum. Research from Northwestern University’s Medill School reports that by 2025, the U.S. will have lost a third of its newspapers that existed roughly two decades ago.

“What’s important to recognize about the decline in local media and the rise of news deserts is that a lot of national news, larger state and municipal news organizations get the majority of their content from local reporting,” database manager for the State of Local News Report Zach Metzger said.

According to the 2022 report, as much as 85% of all news eventually picked up by larger level media organizations comes from local papers, creating a symbiotic ecosystem. However, with the decline of local papers across the nation, Metzger foresees a decline in the quality and depth of stories published at a national level, as well as wavering in the ability for larger media organizations to maintain their current scope.

“What often happens within this ecosystem is that there’s a trickle up of stories to a national level or state level,” Metzger said. “A trickle up of stories to the New York Times, so then it can commit some of its considerable resources far more than a small local paper to doing an in depth investigation if warranted.“  Additionally, local news is more trusted than larger news sources. According to Pew Research Center, 71% of Americans believe that their local news has reported accurate information, whereas 56% do not feel connected to the national news. The widening chasm between journalists and who they cover engenders rampant accusations of fake news, even for trustworthy sites.

Additionally, local news is more trusted than larger news sources. According to Pew Research Center, 71% of Americans believe that their local news has reported accurate information, whereas 56% do not feel connected to the national news. The widening chasm between journalists and who they cover engenders rampant accusations of fake news, even for trustworthy sites.

“When you don’t have interactions with everyday, regular journalists who are regular members of your community, it is much easier to buy into the lie that we are the enemy of the people, which then results in the kind of the situation we’re in right now,” Finneman said.

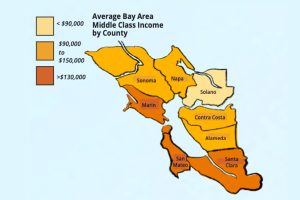

Digital sources, originally viewed as the panacea to the news crisis, are unable to compensate for the over 360 newspapers that have closed their doors since the start of the pandemic. Online news often targets affluent communities, rather than the poorer areas that have already lost their newspapers. Residents also often lack the technology necessary to access digital journalism, exacerbating the information gap.

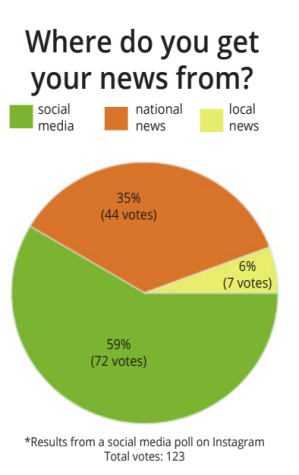

The increased presence of social media in our day-to-day lives has induced new means for news companies and citizens alike to post about and read the news. According to a Pew Research Center poll in Sept. of 2021, around 48% of U.S. adults state that they get their news from social media . Today reading the news can be as simple as looking at a social media platform of choice, reading the headline, and signing off.

Media barons like Gannett Co., Digital First Media and Lee Enterprises Inc. own a large percentage of all newspapers, meaning their decisions deeply impact the state of local news. These companies profligately shut down newsrooms as soon as they are unable to turn a profit, culling countless newspapers. As profits dissipate, many papers cut costs and lay off reporters, crippling their ability to effectively provide news.

“We’re currently owned by Alden Global, a hedge fund,” said Nhat Meyer, a staff photojournalist at the San Jose Mercury News. “So the only thing they care about is how much money we’re making and if we were losing money in any way, they would most likely shut us down.”

California remains as a state with the one of the highest number of journalists: around 3,500 in 2022. But this is not representative of overall trends. There has been a national loss of 34,000 newspaper journalists since 2008. Increased hiring of 10,000 digital-only journalists, since that same year, has not yet been able to amend this situation. Even in California, most papers are clustered in metropolitan or wealthier areas, such as southern California, leaving many poorer areas, like central and northern California, with no news source.

Local publications have historically kept citizens informed of relevant and trustworthy news otherwise overshadowed, and contributed to the heightened accuracy of national newspapers — yet the prioritization of revenue leaves citizens across the country now parched in news deserts.

“The industry has long been telling other people’s stories, instead of our own,” Finneman said. “That doesn’t serve the industry anymore. We absolutely have to tell our own story. Journalism is not dying. It is simply changing.”