There’s no turning frack

Exploring the environmental effects of fracking

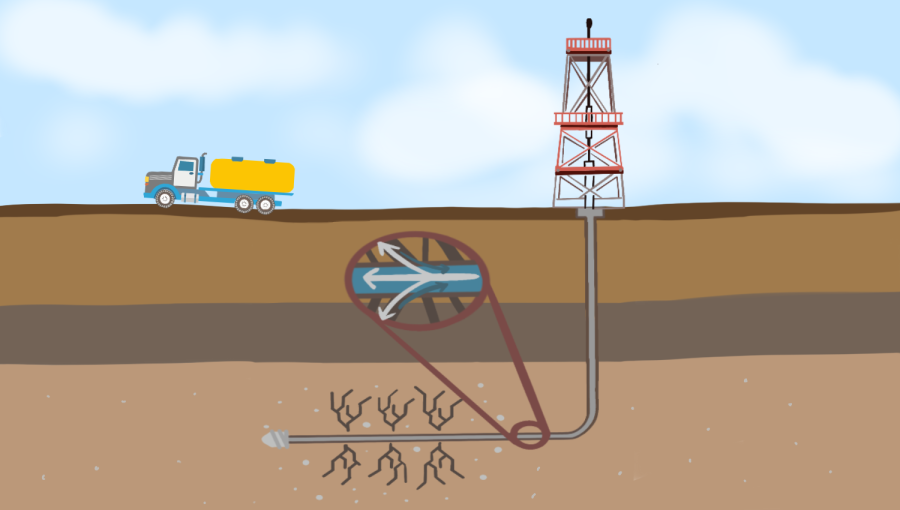

Graphic illustration by In-Depth Section

Fracking injects water and other toxic chemicals into the ground through a drilled hole to extract natural gas.

November 9, 2021

Hydraulic fracturing, a modern method of oil extraction commonly known as fracking, produces a cleaner source of energy compared to other fossil fuels. The actual process of fracking, however, raises environmental concerns regarding the release of toxic chemicals, increased methane emissions and even a heightened risk of earthquakes.

Fracking involves drilling into shale rock, a common type of sedimentary rock consisting of thin layers of silt and clay. Fossils within these layers turn to natural gas after being subjected to extremely high temperatures and pressure over millions of years.

“Fracking injects water and chemicals at high pressure inside the earth which create a fracture network inside the rock and that makes pathways for the gas to flow out of the rock,” Physics teacher and former petroleum engineer Anshul Agarwal said.

The fracking process begins with a wellbore, a hole drilled 2500 to 3000 meters into the ground and lined with concrete and steel to prevent contamination of the surrounding ground and groundwater. From that point, known as the kick-off point, the drill gradually turns 90 degrees and begins to bore horizontally. For another 1500 meters, the well extends parallel to the ground, into the shale rock. The drill is then removed, and a perforating gun is extended into the well to punch small holes through the concrete and steel casing and into the surrounding rock along the horizontal section.

Three to four months later, fracking fluid is injected into the wellbore through the small holes and into the rock, at high pressures that crack and fracture the shale rock. This allows the oil in the rock to flow out and through the cracks into the fluid, which is then pumped out of the well. The oil that seeps out of the fractures following the extraction of the fracking fluid is also pumped out.

Fracking fluid consists of 90% water and 10% proppants — clay or sand that maintain the fractures and allow oil to continue seeping from the fractures — and chemical additives, which differ depending on the conditions of each fracking site. These additives are usually acids to dissolve debris, slickwater to decrease friction and disinfectants to prevent bacterial growth along the well. Often, the chemicals are toxic, which is where the environmental concerns surrounding fracking begin.

Since wellbores extend past groundwater, fracking spills can contaminate usable and drinking water to a disastrous degree. Additionally, fracking companies are not required to disclose the chemicals present in their fracking fluid.

“The fracking companies should disclose the chemicals they are using as injectants into the ground so that groundwater could be analyzed if it is still fit for human consumption in case fracking fluids leak or seep into the water table,” said Agarwal.

Public disclosure of fracking fluid chemicals is recommended by the Shale Gas Production Subcommittee of the Secretary of Energy Advisory Board. However, there are no regulations at the federal level despite earlier efforts to implement them.

Former President Barack Obama said in his 2012 State of the Union Address that he would require the disclosure of chemicals due to public health concerns. Furthermore, the FRAC Act states that a list of the anticipated volume of fracking fluid chemicals should be supplied to the State before and after any fracking operations. Chemicals that must be publically disclosed should be posted on the appropriate website. However, neither gives the State the authority to require full public disclosures of fracking chemicals. The trade secret regulations in a state also factor into how much information companies are required to provide. Each wellbore requires 3 to 6 million gallons of water for use in fracking fluid annually. The amount itself is not significant, especially compared to other industries like agriculture, but it can put strain on local water reserves since fracking sites can be set up anywhere with shale rock formations, including cities and towns.

After being extracted from the well, fracking fluid, now contaminated with naturally occurring radioactive material and salts is referred to as flowback and must be disposed of.

“The real problem is what do you do with the water, because very often, the formation water is very salty, so what you’re getting out is fracking brine,” said Jordan Clark, professor of Geochemistry and Hydrology at the UC Santa Barbara.

The most common method is to inject fluid underground into injection wells, porous rock formations near the fracking site. In rare cases, the pressure from pumping flowback can lead to an increased in earthquakes in the surrounding area. These earthquakes are relatively minor, ranging from a 1.0 to a 4.0 on the Richter scale, at which point they can be felt by humans and can damage infrastructure, especially in areas that lack earthquake precautions.

“Because you are inducing fractures inside the earth, you might be causing little earthquakes,” Agarwal said. “Those earthquakes could build, and could potentially become really big causing more damage.”

Another option for flowback is to recycle it by reusing it for fracking, but this method only further contaminates the fluid following each use. It is also possible to treat flowback at a local water treatment facility and have it released as surface water, but in many cases, these treatment facilities are not equipped to handle fracking fluid-contaminated water.

“I’ve heard reports in Pennsylvania that the company didn’t know what to do with the flowback, so they took it to the local wastewater treatment plant and dumped it there,” Clark said. “Wastewater treatment plants are not designed to remove salt, so the salt went through the treatment plant, and the treatment plant discharged it into a small creek and killed all the fish.”

Besides harming marine life and their habitats, fracking continues to disrupt wildlife as a whole.

“Drilling companies industrialize wild and natural areas where animals live, so it takes away their habitat,” sophomore and Conservation Action Association activities coordinator Apurva Krishnamurthy said.

The combination of industrialization and water contamination poses a threat to California wildlife, such as the California condor and the San Joaquin kit foxes, whose habitat extends throughout areas in California with concentrated fracking activity. Fracking equipment can introduce invasive species into their habitats, and noise from fracking adversely affects migration and reproduction, especially in birds.

Despite fracking’s negative effects on the environment, it continues to be utilized as an energy source because it produces shale gas, a natural gas that generates two times less carbon dioxide than coal, and is considered a viable energy source for the transition toward cleaner energy. Unfortunately, fracking also releases methane, a greenhouse gas that traps up to 80 times more atmospheric heat than carbon dioxide, essentially offsetting the benefits of shale gas.

Since fracking became a commercially viable option for oil extraction in the late 1960s, the nation has seen an increase in accessible energy and a decrease in energy prices, and the process has helped the country become more self-reliant in regard to energy resources.

The political climate surrounding fracking reflects both its pros and cons. In April 2021, California Sens. Scott Wiener and Monique Limon, both Democrats, proposed a bill that would terminate new oil and gas permits, which allow companies to create new fracking sites, by the end of 2021 and end all fracking operations in California by 2027. The main reason for the proposal was to reduce carbon emissions in an attempt to curb climate change. However, opponents noted that natural gases like shale gas do more to reduce carbon emissions than coal, bringing to question whether or not banning fracking is truly the most effective solution to stop climate change. Alternative energy sources also lack sufficient power to provide energy for a state as large as California and based on the availability of current energy sources, the state will continue to be heavily reliant on carbon-based fuels.

Ultimately, Wiener and Limon’s bill was rejected, but California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed an executive order in April 2021 that would ban new fracking operations — not affecting existing ones — effective beginning in 2024, making California the largest oil-producing state to do so. The order aims to completely remove oil extraction in the state by 2045.

Critics of this order claim that banning fracking will place pressure on the job market in areas with fracking sites. In California, 95% of the state’s fracking sites are located in Kern County and the rest of the San Joaquin Valley, providing almost 50,000 jobs. Reflecting the general consensus throughout the U.S., political groups opposed to the order are worried about potential job loss, while supporters are pleased with the environmental benefits and find the proposed timeline to be too relaxed.

Although fracking renders negative impacts on the environment, banning it with no other current proposed energy source remains a controversial topic among lawmakers and voters.