The Pledge of Allegiance: Patriotism or outdated routine?

Graphic illustration by Timothy Kim

The pledge of allegiance is a ritual to students throughout their years of American schooling, but the real meaning of it has been lost.

October 6, 2021

“Please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance”: a statement that makes students instinctively place their right hand over their heart and utter an oath in unison. Whether they like it or not, American students have the pledge ingrained in them, often without knowledge of its history. Students have little choice in deciding whether or not to participate in the pledge at a young age, and once they are old enough to think for themselves, it’s too late — the pledge is already drilled into them. This lack of autonomy when it comes to reciting a tired, xenophobic oath should not be normalized.

Rather than keeping it a tedious routine, schools should educate students about the Pledge of Allegiance, so they can make an informed decision about saying the speech. Additionally, students should not feel excluded based on their decision to participate or not.

Although the words of the pledge seem inclusive, its creation has roots in xenophobia. The Pledge of Allegiance was first introduced in the 1890s by Francis Bellamy, an American minister and author, who initially wrote it as part of a contest for the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in America. While using it as a marketing stunt, a magazine company posted the contest to increase patriotism in schoolchildren by saluting the U.S. flag with an oath. Bellamy also used his oath to define true Americanism in response to the surge of immigrants entering the country at the time. Many Americans in the late 19th century thought that the immigrants coming from southern and eastern Europe — darker-skinned, less likely to speak English and more likely to be Catholic or Jewish — were not like them and could not assimilate into the U.S.

“I view the pledge as a tool to indoctrinate people into America, like ‘this is America and the American way of life,’” U.S. History teacher Kyle Howden said. “I also find it ironic that you have this thing that is perceived as somewhat authoritarian in a country that values individual liberty and free speech.”

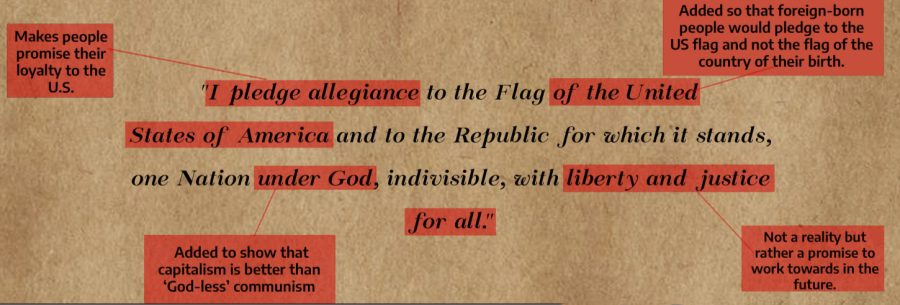

Many words were later added to Bellamy’s original pledge. Congress added the phrase “flag of the United States of America” to the pledge in 1923 because some foreign-born people could have thought of the flag of their country of birth rather than the flag of the U.S. In 1954, the phrase “under God” was added in response to the Cold War and the Communist threat at the time. It was an effort to instill the corruption of communism in the minds of Americans. This addition sparked controversy throughout the country as it was not inclusive of all religions, and it violated the First Amendment, which guarantees citizens the freedom of speech and religion.

While created almost four decades earlier, reciting the Pledge of Allegiance did not become mandatory in schools until the 1930s.

“To me, the pledge itself is a canned way to show patriotism,” AP U.S. Government and Politics teacher Mike Williams said. “It’s also part of the theatrics we engage in, in which we constantly have to announce, in some ceremonial way, how patriotic we are.”

Schools forced students to memorize the pledge to imbue a sense of nationality among them. However, mandatory patriotism inspires the opposite.

“I don’t support everything this country does,” junior Khushi Nigam said. “I don’t ‘pledge allegiance’ to anything. I just live here based on circumstance.”

When students are neither educated nor given a choice about the pledge, they reject the unnatural sense of patriotism they are mandated to display, resulting in further indifference or even budding resentment for their country.

Many students simply lack interest and enthusiasm when they say the pledge. Students have been so desensitized to the Pledge of Allegiance that they do not seem to care what it is that they are repeating.

“I do say it mostly out of habit because once you have been standing up to say it for around 10 years, it kind of just feels like muscle memory,” junior Allison Hsu said.

At Lynbrook, students continue to absent-mindedly repeat the pledge every Friday morning. Instead of just instructing students to say the pledge, Lynbrook should incorporate lessons about the pledge in history classes or deliver them during homeroom. Every Friday, the morning announcements can also include pieces of information about the pledge before students are told to stand up and say the pledge. Learning about the Pledge of Allegiance will inspire students to make informed decisions regarding their patriotism.

“I think when the pledge was first introduced, America was not as diverse,” Hsu said. “I don’t think anyone expected it to be as diverse culturally and racially as it is now. And because of that, I think what the pledge meant back then, and what the pledge means now are two very different things.”

It is important to learn the history of the pledge to shed light on the people left out of American history and understand the necessity of change today. In making their own choices regarding their patriotism, students should understand that saying the pledge does not mean that they completely support the U.S. and that declining to participate does not make them anti-American. A lack of education about something as omnipresent as the Pledge of Allegiance illustrates that schools should revisit their curriculum and find opportunities for students to engage in more critical discussions of some traditions that are regarded as “patriotic.”