Indian government fails to respond to India’s COVID-19 catastrophe

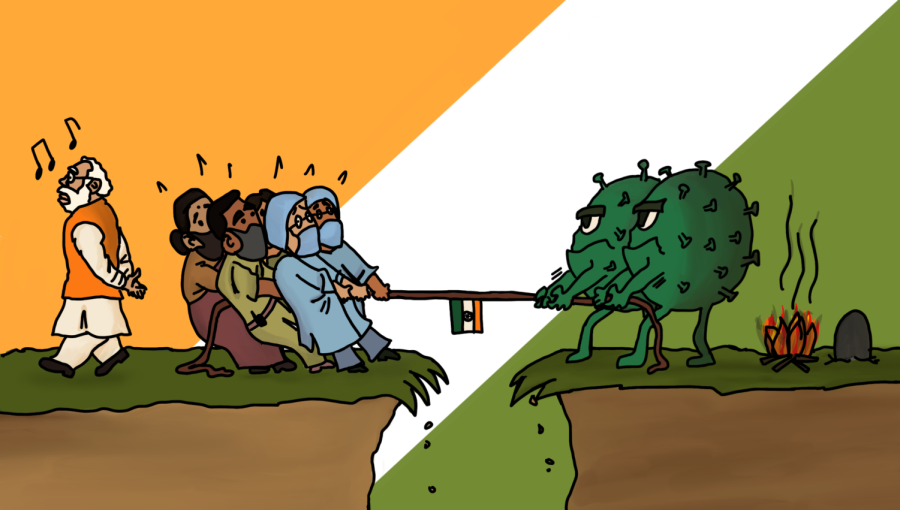

Graphic Illustration by Priyanka Anand

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi turning his back as India struggles to combat the deadly coronavirus, endangering Indian civilians across the country.

May 26, 2021

India is in the midst of a devastating COVID-19 crisis, and any words used to describe it fall short of the horrific reality that millions of Indians are witnessing. The uncontrollable nature of this second wave is largely due to the Indian government’s fatal mistakes and ignorant attitude and its tragic consequences. As the country desperately scrambles to keep its people alive, the Indian government continues to remain alarmingly relaxed in its pandemic response efforts.

As of May 22, India has had a total of 26.8 million cases of the coronavirus, and 304,000 people have died. During the first wave that lasted from March to October 2020, experts predicted that the country would experience immense effects, due to its massive population of approximately 1.4 billion and an average population density of 179 people per square mile. However, government officials prematurely declared that India escaped the severities, attributing the comparatively lower case counts to the government’s supposedly excellent and effective response, and the country opened up by October 2020.

As the world knows now, this hasty decision gave rise to tragedy. Almost every day since mid-April, record-setting deaths and daily case counts — the highest case count for a single day reaching approximately 400,000 — have become the norm and, as experts say and the overflowing cremation sites show, these numbers widely underestimate the true counts by two to five times.

“10 members of my extended family got COVID, and my great aunt actually passed away because of COVID,” senior Anoushka Naik said.

In addition to many different factors, the rapid increase in cases has been attributed to the rise and spread of the B.1.617 variant, which has a higher transmission rate than the highly infectious variant B.1.1.7 originating in the United Kingdom. This B.1.617 variant not only evades the defenses of the immune system but also makes antibodies and vaccines used for other variants less effective.

Although the Indian government was reportedly aware of the threat this new variant posed as early as March 2021, their ignorance toward its severity has expectedly made the situation worse. Thus, they allowed religious pilgrimages and large gatherings to continue through late April 2021, when cases began rising at a rate of 300,000 per day and it was too late to begin implementing effective preventative measures.

Indians are experiencing a heart-wrenching reality, with an all-around lack of oxygen tanks, medication, ICU beds and hospital space for the suffering. People are losing their lives halfway as they wait for a chance at breath and survival, and their loved ones have no choice but to watch helplessly. Lines of ambulances stand outside hospitals, hoping to drop off patients and not bodies.

At such a time, the hopelessness and sorrow of many living through this crisis are rightly turning into anger and frustration toward the government. The relationship of Indian citizens with their government is extremely complex, with some citizens expressing blind devotion and adherence to leaders, while others live mostly uninterested in the government and its actions. However, during a time of immense vulnerability for Indian citizens, a pervasive sense of betrayal is imminent.

“In the worst-case scenario, if people stopped trusting the system, people wouldn’t trust the government to do anything in the future because they haven’t done anything in the past, so you could see a swift change in the political system,” AP Government and Economics teacher Jeff Bale said.

Ever since Prime Minister Narendra Modi was elected in 2014, his popularity has been declining, and it has not improved since his reelection in 2019. This second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic is the largest crisis he has handled so far, and he has proved incapable of prioritizing the health of Indians by facilitating lockdowns and supporting the health care infrastructure.

Nevertheless, his ignorant demeanor and tendency to prioritize his political image over the lives of Indian people are familiar. For example, when Modi was newly elected as Chief Minister of the state of Gujarat in 2002, he failed to stop the killings of more than 1,200 Muslims at the hands of right-wing Hindu mobs during tense communal riots, instead of devoting himself to strengthening his image among his right-wing Hindu base. This time too, Modi’s primary motive during the early weeks of the rising cases in April was campaigning for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the state elections of the eastern state of West Bengal. As late as April 21, he was holding rallies with thousands of attendees and lauding the turnout.

“Everywhere I look, as far as I can see, there are crowds,” Modi said at a rally on April 17, a day with 261, 500 reported cases and 1,501 reported deaths. “You have done an extraordinary thing.”

At the time, daily case counts were rising exponentially, reaching 300,000 within a few days. Modi, more concerned with gaining a BJP majority in West Bengal, one of the few states ruled by a non-BJP party, held rallies until the sixth and final stage of the month-long election when most votes had already been submitted. In the end, the BJP lost the election in West Bengal.

Additionally, Modi permitted the annual Kumbh Mela to occur, where millions of Hindu pilgrims gather at the banks of the Ganges River. The Kumbh Mela, the largest congregation of religious pilgrims in the world, involves a ritualistic collective dip in the waters of the Ganges. This year, widespread ignorance of the pandemic led to crowds gathering without masks for the entire month of April. In letting the Kumbh Mela continue and giving in to the pressures of the right-wing Hindu leaders that form the core of the Hindu majoritarian BJP, Modi and the BJP government displayed a complete lack of care for the health of their citizens.

In the days after the super-spreader Mela, public health organizations ranging from the World Health Organization to local Indian health officials attributed much of the spread of the virus, especially the B.1.617 variant, to the pilgrimage attendees who returned to their hometowns. Countless reports of attendees testing positive and dying have come out — for example, in a town in the state of Madhya Pradesh, 60 of the 61 attendees tested positive upon their return.

Moreover, as the situation worsened in April, Modi gave one of his infamous addresses to the nation on April 20. Although he acknowledged the uptick in cases and deaths, he told Indians that a lockdown should be a last resort and urged individuals to form committees to help protect their own communities. Modi’s avoidance of a lockdown is motivated by his desire to keep the already-declining economy running and not force it to halt like last year, which would make him unpopular among his support base. However, in giving most of the responsibility for the response to local officials and civilians, Modi comfortably took the backseat instead of leading the way and helping allocate resources and restrictions on a more equitable, national level.

“When the centralized government is basically saying, ‘We don’t really want to take action,’ it doesn’t show true leadership of challenge,” Bale said. “This is going to be a bloodbath for Modi’s political movement going forward because ultimately leadership is decided for the best and for the worst in times of crisis.”

The central government’s relaxed response trickled down to city governments, who only began acting around mid and late April to implement local curfews and lockdowns. More importantly, less than half of the states — 14 relatively urban states of the total 29 — have announced lockdowns, with most ending around mid-May. Thus, much of the country’s rural population is not following any form of official safety restrictions.

Expectedly, India’s healthcare infrastructure has collapsed. As people scramble for ways to stay alive, poor leadership from the government and high-level public health officials has made “personal connections” the only way of receiving some kind of aid. People are putting their desperate requests for oxygen tanks, ventilators, medication, beds, food and more on social media platforms like WhatsApp, Twitter and Instagram, which are turning out to be more helpful than the leaders themselves. However, these platforms are mostly helpful in urban areas so the rural population — who arguably needs the most support from the government — is again left to fend for itself. Doctors and nurses’ tireless efforts are the primary reason healthcare is helping people lucky enough to get that care.

“India spends less than one percent of their GDP on healthcare while the U.S. spends around 17 percent, and even we were maxed out on supplies in December,” sophomore Akul Murthy said. “So although the citizens are trying to be resourceful now since they are taxpayers, the government does have some obligation to help them back.”

Many different charities and individuals within India and around the world have responded to the health care infrastructure collapse by providing private supplies to as many people as they can. Naik’s father and his colleagues also set up a fundraiser to deliver supplies to those affected in the cities of Mumbai and Delhi.

“My dad has over 1000 employees in India, and has had some employees who have been hospitalized,” Naik said. “Right now, there’s a dire need for help and support, so [the fundraiser] is just focused on getting the equipment and the gear that they need to treat COVID patients, which will hopefully help support patients more.”

India was also the largest COVID-19 vaccine exporter until the onset of the second wave. The government, touting India’s role in aiding more than 70 countries with a total of 60 million vaccine doses, focused more on their supposedly benevolent image rather than the lives of their citizens. As vaccine production halted in late April, the government’s message now primarily advocates restarting vaccine production as the solution to the ongoing crises, rather than active response efforts.

“My grandparents, who live in India, only just got their second dose and the first appointment that they had for their second dose was canceled,” Naik said. “I very strongly believe that the government is not putting enough of their resources towards solving this crisis and there’s too much focus on what’s going to happen after the pandemic, instead of focusing on saving the lives that are being lost every single day.”

So, as India deals with this catastrophe, what does it mean for the rest of the world? For one, it emphasizes that the COVID-19 pandemic is far from over. As many countries in the West, like the U.S. and the United Kingdom, are preparing to open up in the next few weeks, the gap in progress between first-world and third-world countries is widening every day. Countries like Brazil and Nepal are also dealing with massively debilitating second waves, which should not escape the world’s attention. At a time when the global nature of the pandemic is constantly highlighted, the world needs to prepare a global response. Additionally, the Indian B.1.617 variant has reportedly shown up in 44 countries, including the U.S. and South Africa. With its ability to potentially evade vaccines, this variant of the virus still poses a huge threat to the world as a whole.

India is struggling to survive right now. Although the government and higher officials are not providing adequate attention to the crisis, countries and people in other countries need to contribute actively and provide India with the resources it needs. Saving lives and giving the ailing the luxury of breath are much-needed miracles during this painful time.