Briefly shocking bloody images result in shockingly brief reforms

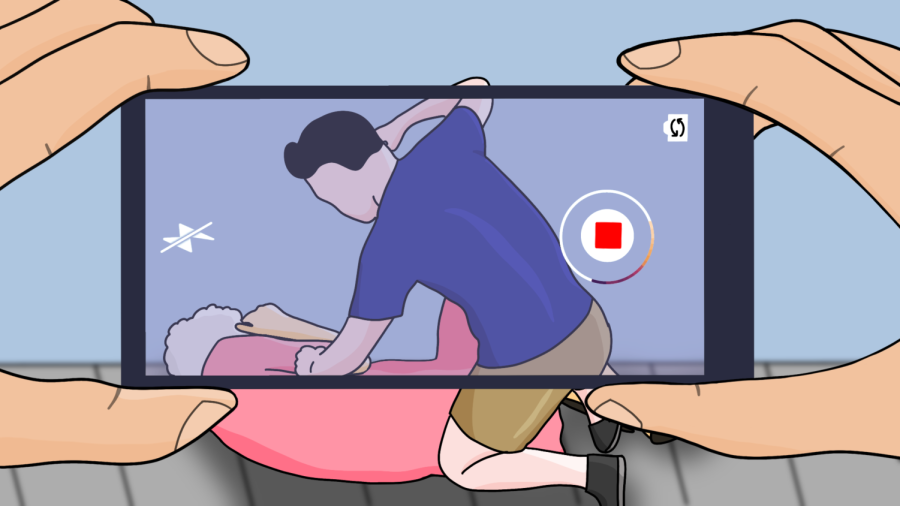

Graphic Illustration by Jason Shan

Videos of racial abuse are being shared all over social media.

May 26, 2021

Social media platforms are marred by the presence of images and videos of violence. While tapping through Instagram stories, one will inevitably encounter gruesome or disturbing visual media: people of color being pummeled to the ground, policemen using excessive force and bloody bodies of victims lying on the ground. While these images may be necessary to highlight modern injustices, the increasing reliance on them to generate social change is worrying. The moral shock inspired by violent media propels meaningful discussions, rallies and protests, but activists and governments alike must seize this momentum to implement educational programs and policies in order to establish long-lasting change.

James Jasper, author of “The Art of Moral Protest,” coined the term “moral shock” to denote the shock experienced by those who are confronted with an egregious view of the world that contradicts their previous regard of reality. Jasper originally applied the term to the animal rights movement, but recent social movements have also employed shocking images to mobilize viewers to attend demonstrations against injustices, especially racial ones.

“I see a lot of moral shock in social media everyday,” said youth advocate and Los Altos High School junior Jeannette Wang, who previously helped organize a protest on behalf of AAPI MV and the 8 by 8 campaign. “Seeing these posts motivated me to do something about the problem at hand.”

Dialing up shock value is clearly effective in creating change to some extent. The 1968 Saigon execution photograph taken by Eddie Adams, in which a South Vietnamese general shoots and kills a handcuffed civilian, was printed on news outlets all over the country and stoked anti-war sentiments, contributing to the U.S. government’s withdrawal from the Vietnam War. More recently in 2020, people took to social media upon seeing videos of the Central Park incident, where a white woman made a racially-motivated 911 call on a black man who was birdwatching, and the subsequent publicity compelled local governments to take action. That same year, the death of George Floyd and the video of a policeman pressing his knee into Floyd’s neck angered thousands to march for police reform.

“Visual images are good at encapsulating a little story or moral in a way so that people immediately grasp the point,” Jasper said. “We can see a villain or victim easily and we know we are supposed to hate and fear the villain and pity the victim.”

Each of these horrifying incidents are defining moments in the national fight for justice. However, the change is often temporary. For those who do not have cultural or social ties to the victim group, the energy to protest social injustice quickly fades. It often takes many incidents for the movements to gain traction and produce concrete results. Before the death of George Floyd, there were the deaths of Michael Brown, Walter Scott, Alton Sterling and countless others. Each re-engagement necessitated the death of another person.

The need for these bloody images as an impetus for change also creates the need for further assaults and attempts of murder to empower the movements. It gives rise to an uncertain future where inequalities may persist simply because of apathy. Moral shock may be the current marketing tactic, but, as people grow desensitized to each new shock, the energy behind each movement may fall as well.

“Moral shock can be the start of longer processes, or it can just disappear,” Jasper said. “You cannot go around being shocked for long. The effect wears off.”

The Stop AAPI Hate movement, fueled by viral photos and videos of physical assaults on elderly Asian Americans, has recently garnered attention. The reporting on the violence perpetrated against senior citizens Ngoc Pham and Xiao Zhen Xie was accompanied by a video that depicted the bloody faces of both the assailant and Xie. The Instagram post gained 1 million views and more than 6,000 comments; while the post brought national attention to a systemic issue, the motivation was largely short-term. Even now, the momentary feeling of shock experienced by viewers is being dismissed and forgotten.

Similar to the death of George Floyd, when headlines broadcasted the Atlanta shooting and other crimes, protests occurred almost immediately, some even happening in the same week of the incidents. The reporting on shocking injustices offers a clear next step: to go out and march. However, where things proceed from there is less apparent. Demonstrations effectively signal that change is needed, but there are multiple pathways as to how that change should be enacted.

Activists should take advantage of the initiative spurred by the first instance of injustice to create long-lasting foundations of change. Protests and rallies make a social movement capture national attention, but education and legislation address the key issues behind the injustices. While it is unrealistic to ask each person to give constant attention to each movement, even those who are not deeply involved in activism can help in other ways, such as signing petitions and voting.

Certain kinds of changes are long-term in addressing society’s pervasive racism, but many are surface level and only combat the more obvious symptoms of racism. The federal COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act is an example of the latter. The legislation aims to expand investigation into hate crimes and allow for better reporting, but the bill only addresses issues after a hate crime has already been committed, rather than combatting the root cause.

“Even though we protested for a long time, a lot of government agencies aren’t really changing anything,” sophomore Dennis Han said. “There’s a lot more awareness, which is good, but racism is still out there.”

Fortunately, the multiple instances of racism did give rise to other forms of legislative reform. Youth advocates have been particularly vocal, and further resolutions, such as the push for ethnic studies programs, are underway.

“Methods to encourage more long-term involvement include involving youths and other niche groups as leaders,” Wang said. “We could also increase education and awareness, such as letting people know the experiences of Black Americans and the inequities they face in their daily lives.”

The recent brutality against POC communities has successfully spurred a call for unity and racial equality. However, in order for the movement to effect meaningful change, everyone, including those outside of the AAPI community, must act to combat hate at all times. Because the need for equality is not contextual but perpetual, the demand for equality must be similarly unyielding.