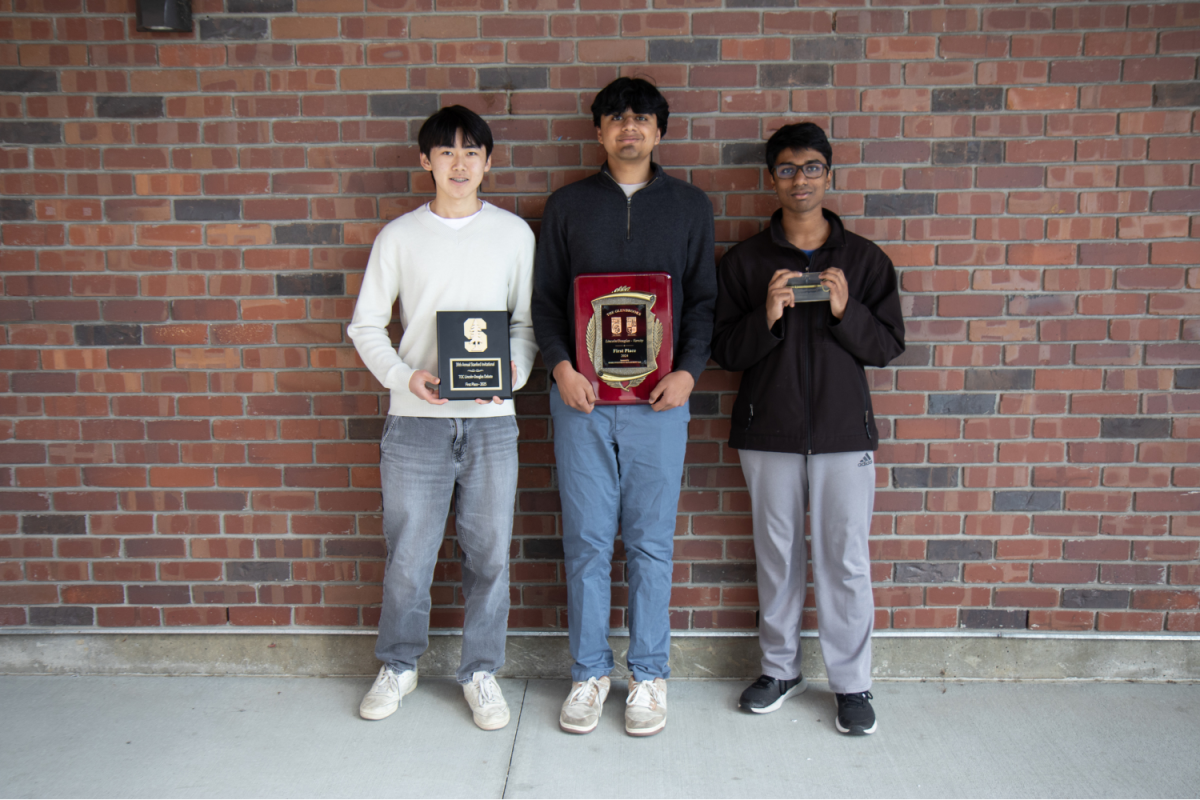

For juniors Om Modi, Vikrant Vadathavoor and Bolang Zhu, it’s all about speed. During debate competitions, they fire off arguments as fast as they can. Judges watch as their opponents furiously take notes for their own rebuttals, all while the remaining few seconds tick away. In the fast-paced world of Lincoln-Douglas debate, all three have reached all-time high rankings of No. 1, No. 5 and No. 1 respectively, standing as some of the top debaters in the country.

Modi got his first taste of speech and debate while in middle school, when he joined the Athens Debate academy, while Vadathavoor and Zhu started debate as freshmen at Lynbrook. They had two options: traditional LD, which focused on a slower speaking pace at mostly local tournaments, or circuit LD, which involved extremely fast speaking and highly technical arguments. They tried circuit LD and instantly enjoyed it due to its high intensity, tough competition and possibility for competing in national tournaments.

“The year we joined, Lynbrook’s only functioning event was Lincoln-Douglas,” Vadathavoor said. “The team captain created a community within LD, which is why we signed up.”

The circuit LD debate format is a one-person event that is charged with intensity. Each debater is given a few minutes to prove their argument, often speaking as fast as they can. The schedule is tight: 6-minute speech, 3-minute cross-examination by the opponent and a 4-minute preparation time. This repeats, alternating competitors, as judges follow the rapid speeches using flowcharts. Every second counts as debaters fight against pressure to win over the judges by outpacing their opponents.

“One of the challenges is sounding incoherent because we are speaking so quickly most of the time,” Zhu said. “We often risk sacrificing good delivery by speeding up.”

Modi and Zhu attended their first tournament as freshmen at the Nano Nagle Round Robin, while Vadathavoor competed for the first time at the Coast Forensic League, all in their sophomore year. The three, with no experience, found themselves mixed in with seasoned debaters. They struggled to adjust to judging styles, pressure and how to respond to arguments in a fast-paced environment. Many of the technical terms they had studied only gave way to more branches of philosophical theory and procedural rules, and they ultimately weren’t able to take home awards. Regardless, they were hooked.

“While we didn’t do well, it was a really good learning experience,” Modi said. “The community of LD debate and our experiences drove us to improve ourselves over time.”

As freshmen, the three familiarized themselves with LD rules and all its jargon. Now, they spend more than two hours a night on research for competitions, perfecting their speaking voices and rattling out arguments and rebuttals until they are foolproof. Preparation goes beyond research; the three keep an eye on almost every competing school across the country, studying each of their methods and styles.

“One school in Texas or another school in New York might be on their radar,” Lynbrook debate coach Michael Harris said. “They aren’t just working really hard, they’re also plugged into what’s going on and what other schools are up to.”

Earlier in their debate journeys, Modi, Vadathavoor and Zhu were stunned by the high pace and pressure of competitions. The three have worked with Harris to improve their skills and rise to the top of national rankings. In long study sessions with the support of each other, they have studied topics from environmental justice to capital punishment to foreign policy. Through that, they have mastered staying calm under pressure and the need to be flexible when faced with new topics.

“A lot of the most memorable parts are not from the actual tournaments,” Modi said. “We are also hanging out with friends during them and meeting people from different schools.”

Currently, Modi, Vathadavoor and Zhu are studying for the Tournament of Champions, one of the most prestigious debate tournaments for high school students in the country. It’s in the name; they will go against students from across the country, covering the involvement of the United Nations in foreign treaties. In order to get into the TOC, they each had to win two bids, something awarded to competitors who placed highly in a tournament, making it into the top 80 students chosen out of over 2,000. This is Vadathavoor’s first year qualifying for the TOC, after he achieved five bids as early as September.

“People from around the country go to the TOC,” Vadathavoor said. “There’s a whole two-month break before it because it gets really serious.”

In sophomore year, Modi and Zhu became captains of the LD debate team. Adjusting to the responsibility as sophomores meant studying for the TOC while also mentoring younger students. This year, the two are Directors of Tournaments, choosing where the debate team competes throughout the year, while Vadathavoor is the new captain. During study sessions, he teaches the underclassmen how to effectively divide up research and oversee scrimmages. The three have tried their best to ensure younger debaters have the same passion for LD as they did.

“One part of training has been simulating what tournaments are like for the younger students and then giving them feedback,” Zhu said. “It’s about the small stuff that makes us good as a team.”

On April 24, the three will conclude their debate season competing at the University of Kentucky for the TOC. Next year, Modi and Zhu will be president and vice president of Lynbrook debate, continuing to lead their team while balancing their final competitive season. Vadathavoor will return as LD captain, and the three will mentor a new generation of debaters, passing down everything from intense competition to late night preparation in the fast-paced world of circuit LD.

“I’ve been coaching for 12 years, and I’ve never seen a group of kids do as well as Modi, Vadathavoor and Zhu,” Harris said. “I’m super proud of them.”