“Are we in a constitutional crisis?” NPR’s Nina Totenberg asked, mirroring the sentiment of many. Interview after interview, Democratic congresspersons answered similarly, mentioning that we are nearing a constitutional crisis. In headlines and on social media, the term “constitutional crisis” has been a constant within the early months of Trump’s presidency, as his administration continues to clash with immigration and state and federal courts. Despite these heated exchanges, constitutional crisis is a broad term, and there are no clear markers to define when a country has truly entered one.

“The constitution is, to an extent, a set of rules about how the government will operate,” political science professor at San José State University James Brent said. “When you get to a point where either there’s a conflict between two branches of government or some other situation comes up where the roadmap runs out and you’re in uncharted territory, that’s what we’d call a constitutional crisis.”

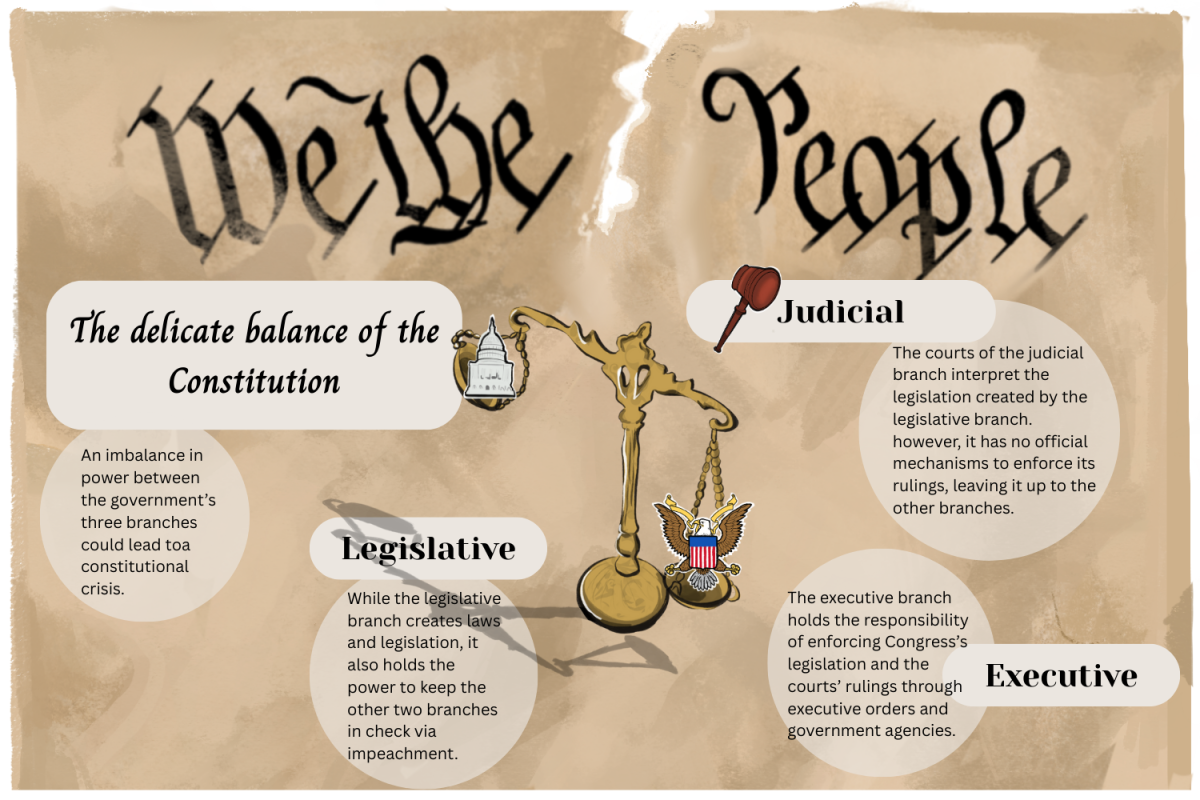

The foundational aspect laid out in the Constitution to avoid a crisis is the system of checks and balances that prevents one branch from overpowering another. The three branches within the Constitution — the judicial, executive and legislative — were crafted to adapt this process.

“Checks and balances are crucial because our country is founded on these principles,” junior and Politics Club president Chelsea Guo said. “They’re why we have three branches in our government, and they’re the basis on which the Constitution was written. It’s important that we make sure these systems are as strong as ever, whether it’s resisting corruption, or just making sure that the system is still running in the same fashion that it’s supposed to run 200 years after the Constitution was written.”

The executive branch, consisting of the president, has the power to be the tie-breaker in Congress and sign or veto laws put forth by Congress. The legislative branch, consisting of the Senate and House of Representatives, can approve or disapprove the President’s cabinet member picks and vote to impeach the President or judicial judges. Meanwhile, the judicial branch can review and strike down existing laws as well as the President’s executive orders by declaring them unconstitutional. A constitutional crisis can occur when one branch ignores the authority of another.

The prevalent use of the term in 2025 has been sparked by concerns about actions that the Trump Administration took in March. Many consider those actions violations of court orders, thereby triggering an imbalance of power between the two branches. On March 15, Washington, D.C. District Court Chief Judge James Boasberg ordered the government to return the two flights carrying immigrants and alleged undocumented Venezuelan gang members being deported under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, a law previously used to deport non-citizens deemed dangerous during wartime. The Trump Administration ignored the order, continuing operations as several more flights took off to deport alleged illegal immigrants. As a result, concerns about the implications of a presidential administration ignoring a court order began to circulate rapidly, and debates sparked over whether or not the country could be falling into a potential constitutional crisis.

“The problem is that those checks mean nothing if they’re not able to be used,” Brent said. “You’ve got a Republican President, a Republican Congress and a Republican-controlled Supreme Court. If they’re all on board with violating the Constitution, then there really isn’t much that can be done. This means that, over the long term, the only checks are the elections, where voters have an opportunity to weigh in every couple of years.”

Defying a federal order may constitute contempt of court, which is a legal offense that can lead to fines or imprisonment. For a sitting president, such defiance of the order could be interpreted as an abuse of power, which, if charged, could lead to impeachment. The Trump Administration continues to defend its actions and attempted to impeach Boasberg for “abuse” of power. Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John G. Roberts Jr. rebuked critics of Boasberg and their attempts to impeach him.

On April 10, the Trump Administration once again clashed with the courts: the Supreme Court ordered that the Administration must “facilitate and effectuate the return” of Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia, an alleged undocumented Venezuelan gang member who was wrongly accused and deported. Despite this, the Trump administration has argued that this does not mean it is necessary for them to take action to return him to the United States.

“Trump’s decision undermines the Court’s name because the court lives off their orders and people listening to them,” sophomore Prajwal Avadhani said. “The United States Supreme Court has the highest respect; even if you lose a case at the Supreme Court, you still respect their decision. But if someone openly disobeys the Supreme Court, then why have a Supreme Court?”

The Trump Administration’s deportation case brings up the importance of due process, a Constitutional agreement that requires the fair establishment and enforcement of legal procedures that respect and protect an individual’s rights, including one’s right to property and liberty during the legal process.

Past conflicts between the branches of government and a clear understanding of where the constitutional roadmap ends can help to decipher the implications of a potential constitutional crisis occurring today and why it’s happening. One past example is former President Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal. During his first term, a group associated with Nixon’s re-election campaign broke into the Watergate Office, the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the time, to bug the building. Later, Nixon tried to cover up evidence of his involvement and refused to release evidence to the investigators of his case, turning the case into a constitutional crisis. Closing in on impeachment, Nixon later resigned to “save face.”

“When Richard Nixon was going through the Watergate scandal, everybody agreed on the facts,” social studies teacher David Pugh said. “All the major news networks covered them in the same way; you switch channels and everyone still gets the same story. That’s not the situation now. Depending on what podcast you watch or which news outlet you read, you get a completely different interpretation of what the facts are.”

Media bias isn’t the only contributing factor, either. Partisanship in government could also play a role in pushing an administration closer to a constitutional crisis.

“Polarization in the government has made impeachment an almost completely ineffective check on the President, whereas in the 1970s, it was a check,” Brent said. “Nixon resigned his presidency because evidence came out of abuse of power, and the fact was that he was going to be impeached and there was significant Republican support for the impeachment. Today, that would not happen because there would probably be only three or four Republicans who would vote to impeach Donald Trump under any circumstances.”

Whether it’s because the constitutional checks and balances fail or that the due process is not properly implemented, both the past and the present have shown how a constitutional crisis details a time when there is no clear-cut way to resolve a conflict under the Constitution.