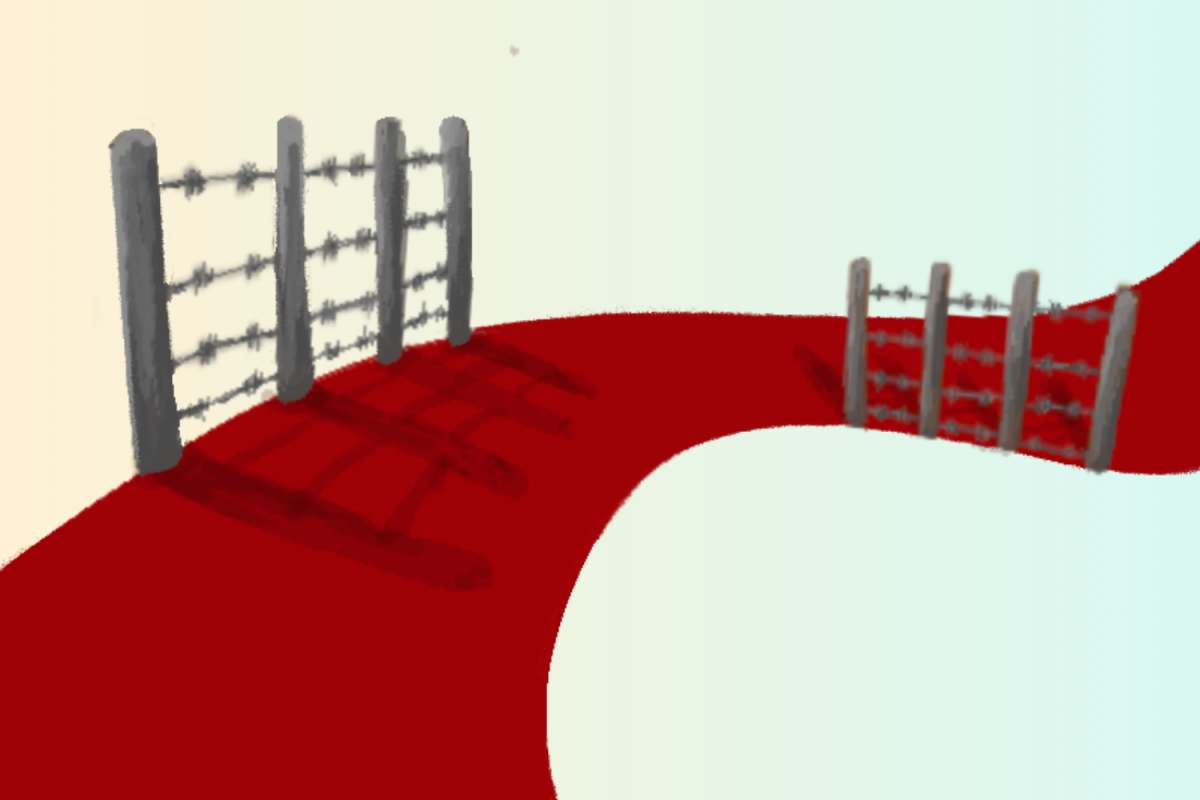

From the literal red lines that encircle dated communities to invisible socioeconomic barriers, redlining is characterized as the discriminatory practice that refused minority groups the same financial services and home ownership offered to their white peers. It has plagued the country, including the Bay Area, since 1934. Although the practice has technically been outlawed, its shadow continues to loom through the segregation and inequality that persist in the present day.

“It’s the less spoken about or less obvious element of the civil rights movement,” history teacher Kyle Howden said. “It’s not that visible — it’s an underlying thing that’s there.”

Dating back to the United States under President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration, the National Housing Act of 1934 created a Federal Housing Administration and Home Owners’ Loan Corporation to combat the national housing shortage by increasing America’s housing stock. In prioritizing the flourishing of suburbs, which they viewed as incompatible with minority residents, they created segregated areas on maps ranging from red for “hazardous” neighborhoods to green for “desirable” suburbs. Red neighborhoods usually consisted of minorities while green areas that were considered to be profitable were largely populated by white communities. Their logic surrounded a belief that because African Americans or other minority communities were deemed “undesirable” at the time, it would put their loans and investments at risk. Consequently, financial institutions enforced higher down payments or interest rates for the loans of those in lower socioeconomic income areas and deflated appraisals on their homes.

Although the HOLC and similar estate corporations explained redlining as a way to protect them financially from those who may not be able to repay loans, the factors considered in marking a location red held inherently negative connotations. For instance, HOLC described redlined Area D11 inhabitants in San Jose, as an “infiltration of Slavs, Portuguese and Mexican” people. An extensive interactive project mapping inequality in America by the University of Richmond demonstrates multiple instances of prejudice in redlining maps, listing categories for “favorable influences” and “detrimental influences” in each region. Yet, many of the “detrimental” influences were what they called “heterogeneous development” — to them, diversity was unfavorable.

Likewise, while the HOLC aided middle-class Americans with generous mortgages, minorities, who were denied access to affluent communities based on race, didn’t receive the same offers. In contrast to white Americans who purchased homes at lower prices and saw their home values appreciate, African Americans were trapped in less established neighborhoods. Without the privileges of accumulating assets that would ensure generational wealth, misnomers about those trapped in these conditions being lazy or unwilling to work hard began to spread.

“Redlining, to some degree, explains the wealth inequality between different racial groups,” Howden said. “It has nothing to do with being ‘lazy’ — it has to do with opportunity along the way to amass more wealth.”

Even if minority groups were fortunate enough to purchase houses, these homes generally did not appreciate due to the area’s lack of investment; the majority ended up in vicious, high-marked cycles of rent-controlled by landowners, who inflated prices knowing that minorities likely had no other neighborhoods to go to. With less invested-in areas came lower incomes, fewer work and education opportunities, increased policing and a cycle of lower-grade infrastructure that restricted their social mobility. For example, West Oakland — the redlined, black-majority urban center of Oakland in the Bay Area — was denied access to quality schools, grocery stores and financial capacity for home ownership. These privileges could be found near the green-lined areas of Oakland’s hills.

“In the suburbs, the school districts are great,” said home loan officer Christina Lozano at Crosscountry Mortgage, who specializes in working with minorities. “Most people are well educated — our tax dollars go to repairing a lot of the infrastructure, which means more families want to move there. Conversely, in previously redlined areas like West and East Oakland, your cars get busted from driving through the damaged potholes and it’s tough in that area.”

Indeed, while the Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibited redlining and tasked federal financial regulators — primarily the Federal Reserve — with enforcement of the policy, the effects of redlining still linger across the nation. Upon further examination of redlining maps, it is common to find discrepancies between the color grade assigned to an area and its actual racial makeup. Faced with the physical and economic barriers of redlining, many groups moved out of redlined neighborhoods in waves once they were financially able to. In response, white communities expanded outward, leaving their original neighborhoods following the increase in diversity. The result, as seen in cities like Detroit, was “white flight,” in which large groups of white Americans moved out to mostly federally subsidized and racially homogenous suburbs. Thus, even without strict lines on a map, racial discrimination that separated groups of people from each other was largely a product of redlining.

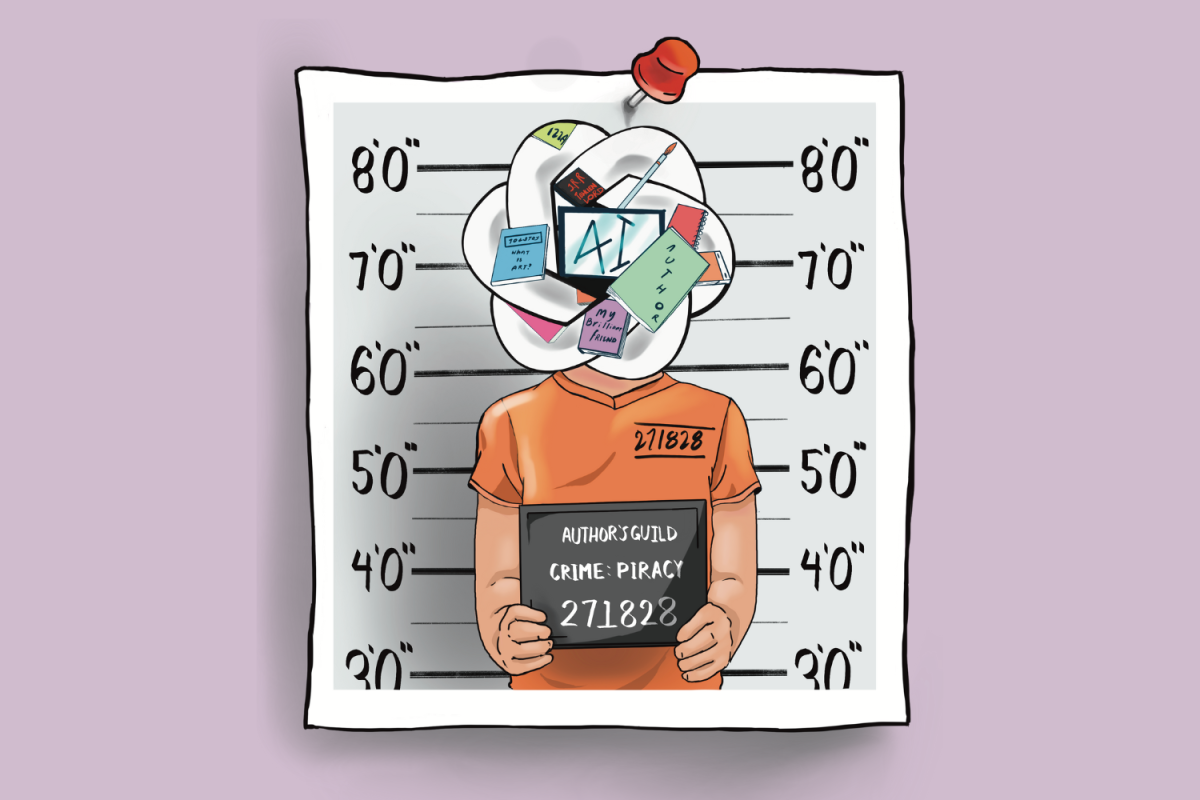

In attempts to remedy the consequences of redlining, policies such as the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 were enacted, which put added pressure on financial institutions to help meet the credit needs of communities including low to moderate-income neighborhoods. These programs helped pave the way for additional government efforts to take on subsidized housing projects or provide certain minorities with additional resources for attaining housing. Still, the undoing of 40 years of redlining would require the long-term enforcement of nondiscriminatory real estate practices.

Lozano explained that the current approval of home loans requires specific documentation, mainly to prevent fraud and evaluate individuals objectively. When seeking to attain loans from large commercial banks such as Chase or Wells Fargo, this could present potential barriers to people who do not fit the traditional financial profile. However, some smaller, more targeted banks that specialize in specific types of loans like mortgages can have lower requirements. In practice, the modern real estate industry has gained flexibility in adapting to individual client circumstances amid rising regulations.

In the present day, areas including West and East Oakland, as well as the San Francisco Metropolitan Area are seen as hallmarks of the negative effects of redlining. West Oakland was entirely encased in highways that divided neighborhoods dominated by people of color, restricting possible interracial encounters. In the process, over 5,000 homes were demolished, creating the highest rates of pollution per capita in Calif. and causing immense detriments to personal health. Populations in previously redlined areas were twice as likely to go to the emergency room for asthma and more susceptible to cardiovascular disease, maternal morbidity and adverse birth outcomes — trends that still continue today.

Larger, more apparent impacts of redlining involve the general atmosphere within the communities created. Many were built on broken foundations, making them less desirable for future improvements in outsiders’ eyes. Investors saw them as unattractive or unworthy, with some of the most consequential effects being worse public schools or hospitals, leading to less funding and public access. The expectation that these neighborhoods are worse off raises the alarm for increased police presence, which only heightens the chances of violent encounters between the local police and people of color.

“Redlining has long-lasting effects in modern day,” English teacher Vanessa Otto said. “Among them are modern-day segregation and lack of access to wealthier neighborhoods and their resources. Even the houses that were negatively impacted by redlining today are still in locations where they’re closer to dangerous chemicals with less access to better-funded schools.”

Despite this, teachers and educators alike create American history and literature curricula that raise awareness of the cycles of redlining, decreasing the probability that redlining or similar modes of segregation respawn.

“It’s part of the lingering effects of redlining where African Americans were just segregated into ghettos, they weren’t able to leave,” junior and American Literature student Matthew Tanaka said. “They weren’t able to find the opportunities, the education. In school, I think it’s good that it’s taught and learned in order to understand how impoverished places emerged in American society.”