Hailing from the Greek words nostos, or homecoming, and algos, meaning longing, nostalgia offers us an opportunity to relive the past. Although it is generally accepted as an emotional phenomenon that brings about pleasant feelings, nostalgia was previously believed to be a psychiatric disorder, much less a warming experience.

In the late 17th century, Johannes Hofer, a medical student at the University of Basel, noticed a strange illness affecting Swiss mercenaries serving abroad. He saw them struggle with fatigue, insomnia, irregular heartbeat, indigestion and fever, sometimes leading to death. The symptoms were so strong that soldiers were often discharged and sent home. Hofer later realized that the cause was an intense yearning for their mountain homeland in Switzerland.

At first, nostalgia was considered to be an exclusively Swiss “affliction.” Doctors theorized that the constant sound of cowbells in the Alps caused trauma to the brain and eardrums. Because of the unfamiliarity of these feelings, people misidentified a combination of PTSD, neurosis and fatigue caused by the war as nostalgia. To avoid nostalgia, commanders forbade soldiers from singing traditional Swiss songs, fearing that they would experience desertion or commit suicide.

“It was ideal for a doctor to say that a nostalgic person is experiencing mental illness because it serves the interests of the nation that is at war,” said Steve Nava, chair of the sociology department at DeAnza College. “The classification is a justification for violence.”

The 17th century was largely characterized by a culture of conformity; thus, many people were discouraged from confronting the status quo, especially leading figures, like scientists, who believed nostalgia was a disease. People didn’t think to question the phenomena due to the fear of standing out.

“In a state of conformism, it’s hard to question medical thinking and other official ways of psychiatric thinking,” Nava said. “And so I think that’s one reason why it becomes pretty biased towards those that do control knowledge.”

Nostalgia eventually became officially classified as a disease during the last quarter of the 18th century and was used to diagnose the soldiers in the French army during the Revolution and Napoleonic Wars. However, when the wars ended, people no longer classified nostalgia among soldiers as a disorder, and nostalgia became less stigmatized. However, it was still diagnosed as a disease around the world in other contexts.

“Dispelling the myths of war being a moral act could have been a transitional point,” Nava said. “The discursive shift from medicalizing an emotion like nostalgia shifts the perspective to it being a natural and organic emotion.”

As migration increased worldwide, various groups were more aware of their nostalgia due to the exposure and understanding of the concept. As more people started discussing psychology and natural human behavior, people started to agree that the term refers to anyone who was separated from their homeland for a long time.

By the early 20th century, professionals no longer viewed nostalgia as a neurological disease, but as a normal human tendency. Psychologists speculated that it represented difficulties in letting go of childhood or a longing to return to one’s fetal state.

“It could be a coping mechanism,” Nava said. “There’s always a bit of uncertainty in the present moment, especially during times of change so nostalgia just reminds us of a simpler, less intense time.”

During the following decades, the general interpretation of nostalgia shifted in two major ways. Firstly, the definition expanded from general homesickness to a greater longing for the past. Some started believing it to be a generally poignant, more pleasant experience rather than a disease. One infamous case captured these exact sentiments; it followed the behavior of French author, Marcel Proust. In his novel “À La Recherche du Temps Perdu,” or “Remembrance of Things Past,” he described that eating a madeleine cake, which he had not tasted since childhood, triggered a cascade of warm sensory memories.

“When I think of nostalgia, I generally associate it with positive feelings,” senior Naomie Gardette said. “I associate the word itself with good memories.”

The second part of the shift away from the generally accepted views of nostalgia was advancements in science. Psychologists began relying on empirical and systematic observations rather than pure theory; they began to understand that experiencing negative emotions was correlated with nostalgia rather than a direct effect of it. In fact, they began to realize that although it has been linked with negative symptoms, such as sentiments of sadness and loneliness, nostalgia generally does not put people in a long-term negative mental state, like depression. Instead, the phenomenon allows people to memorialize meaningful experiences, boosting one’s psychological well-being.

“I view nostalgia as a way to escape from the present, whether the present is good or bad,” Gardette said.

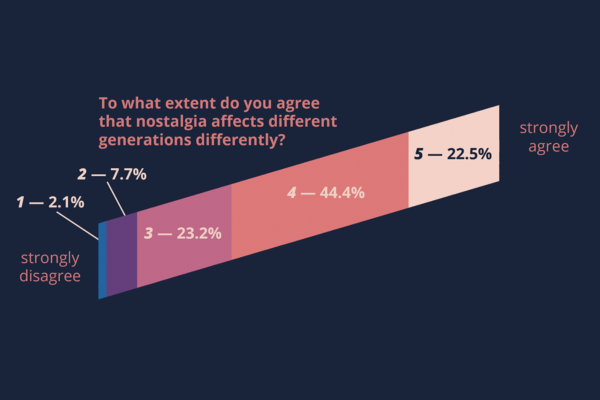

Through observational studies, scientists began to realize that nostalgia in fact boosted self esteem, psychological growth, charitable behavior and social belonging. Nostalgia has become a restorative method to cope with distress and restore well being. According to the Human Flourishing Lab, in a survey of more than 2,000 American adults, 84% agreed that nostalgic memories serve as reminders of what is most important in their lives. In addition, 77% believe that, when life is uncertain or difficult, nostalgic memories are a source of comfort and 72% use them as inspiration in their daily life.

This is partly the reason why nostalgia has become a powerful marketing tool in the media. By reliving past experiences, viewers not only feel good about themselves but they understand that their lives have purpose and they can tackle current and future challenges.

“In our own emotional lives, we should reflect on our nostalgia with a critical lens, but also one in which we welcome it as a natural emotion,” Nava said.