Ever heard of pigs leading a revolution and seizing total domination over a government? No? Well, that’s satire for you: truth, dressed up in absurdity and hidden between the lines. Satire is a common means of social commentary on society and politics, but manifests commonly within literature and comedy. So, why is satire so effective? Or, subject to wrong interpretations, how can satire be detrimental?

Satire is a technique used by writers to expose and criticize the norm of an individual or a society, employing humor, irony, exaggeration or absurdity to ridicule. It pokes fun at social issues, often with a goal to drive social change. George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” is a perfect example of satirical literature: Orwell imbues irony and absurdity into a story about mistreated farm animals to criticize the Russian Revolution and the subsequent Stalinist era.

“Satire may not necessarily offer a solution,” English teacher Terri Fill said. “But it gets us to notice something about ourselves or our society by ridiculing it and bringing it to our attention. It causes us to reflect and hopefully think of our own solutions.”

The origins of satire can be traced back to ancient Greece, where playwrights like Aristophanes mocked political figures and societal norms using satire in theatrical comedies. During the Renaissance, authors such as Geoffrey Chaucer and Desiderius Erasmus addressed corruption in the Roman Catholic church and government with satirical literature. Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” suggests the eating of Irish babies as a solution to poverty, using absurdity to highlight the inhumanity and indifference of British policy toward the Irish poor. French satirists of the same period, such as Voltaire, used juxtaposition to develop incongruity of the brutal realities in life with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s optimistic philosophies, ultimately to criticize societal and religious hypocrisies.

The power of satire lies in its ability to engage readers with thought-provoking absurdity or humorous dialogue, even sustaining attention from audiences with opposing viewpoints. As an author reels the reader into developing connections with characters or story plots, satire serves to prompt reflection on serious subjects in a manner that is entertaining and lighthearted enough to not come off as overly direct.

“Satire ridicules something about ourselves or our world,” Fill said. “Ridiculing whatever needs to be changed in society is a way to get people to laugh at it and realize that they don’t want to be part of it. Nobody wants to be ridiculed.”

The three commonly recognized rhetorical tools used in satire are exaggeration, irony and catharsis. Exaggeration emphasizes flaws of its subject matter to bring attention to its ridiculousness. Irony and sarcasm — saying one thing but meaning another — can indirectly convey a message by mocking the gap between reality and perception. By poking fun at societal tensions, satire can offer a sense of catharsis for those who may feel oppressed by these tensions.

“If you pick up a book and it doesn’t really interest you, then you’re not gonna read it, right?” junior Daniel Wan said. “But if it can make you laugh and draw you into the story, then you’re gonna want to read it more.”

In education, satire is applicable in history and government classes when dealing with political cartoons. For example, “The Bosses of the Senate,” an American political cartoon by Joseph Keppler, illustrates the overpowering influence of big business on the United States during the late 19th century by portraying industrial magnates as gigantic figures looming over the Senate chamber. The senators are shown as dwarfed and overshadowed by colossal businessmen, suggesting that legislative decisions were heavily biased in favor of big business.

“Political cartoons are often satirical by the way they are drawn; most of them only use short phrases of text,” history and government teacher Mike Williams said. “However, you have to be careful about using satire because it may have a particular political point of view that might not sit right with others. For this reason, teachers are encouraged to teach political cartoons, which may contain satirical messages, in a way that proper background or context is given first, or during a lesson in a way that provides for objective analysis on overall understanding.”

Aside from history, satire is also largely used in literature. In the satirical novel, “The Pamela Papers: A Largely E-pistolary Story of Academic Pandemic Pandemonium” by Nancy McCabe, a writing professor at University of Pittsburgh at Bradford, McCabe satirizes the chaotic realities of academic life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I would not have tried to write a satire at any point in my life before this novel because I knew that it was hard and people could misunderstand it,” McCabe said. “If you’re not funny enough, if you don’t hit the right way, people could miss the satirical element. Everything that was going on in my workplace was so absurd, it seemed like the best way to write about it was by highlighting that absurdity. So the satire evolved from there.”

The novel satirizes the sudden shift to digital platforms, the struggle to adapt teaching methods and the complexities that educators and students face. By exaggerating these elements, McCabe offers a humorous yet insightful critique of education’s readiness and response to disruptions.

AP Language and Composition classes also explore satirical literature in rhetorical analysis. The extent of satirical works’ absurdity can cause great offense if not interpreted correctly, making satire a crucial genre to be able to identify and analyze.

“If you don’t hear the tone, you may miss the point, and you might even misinterpret the entire passage,” Fill said. “So it’s very important to hear the tone in order to correctly interpret the message.”

Satire provides an engaging platform for individuals to initiate change with their voices. In stand-up comedy, comedians like senior Aakash Choudhary use satire to present serious issues in a comedic light, inviting audiences to reflect on these topics without the weight of direct confrontation. This approach not only makes complex subjects more accessible but also encourages listeners who might otherwise avoid such discussions.

“People resonate more with satire than they do with fake political outrage you might normally see in the media,” Choudhary said. “When I write my satirical bits, I think of what bothers or amuses me, and how I can take these to the extreme in a comedic fashion.”

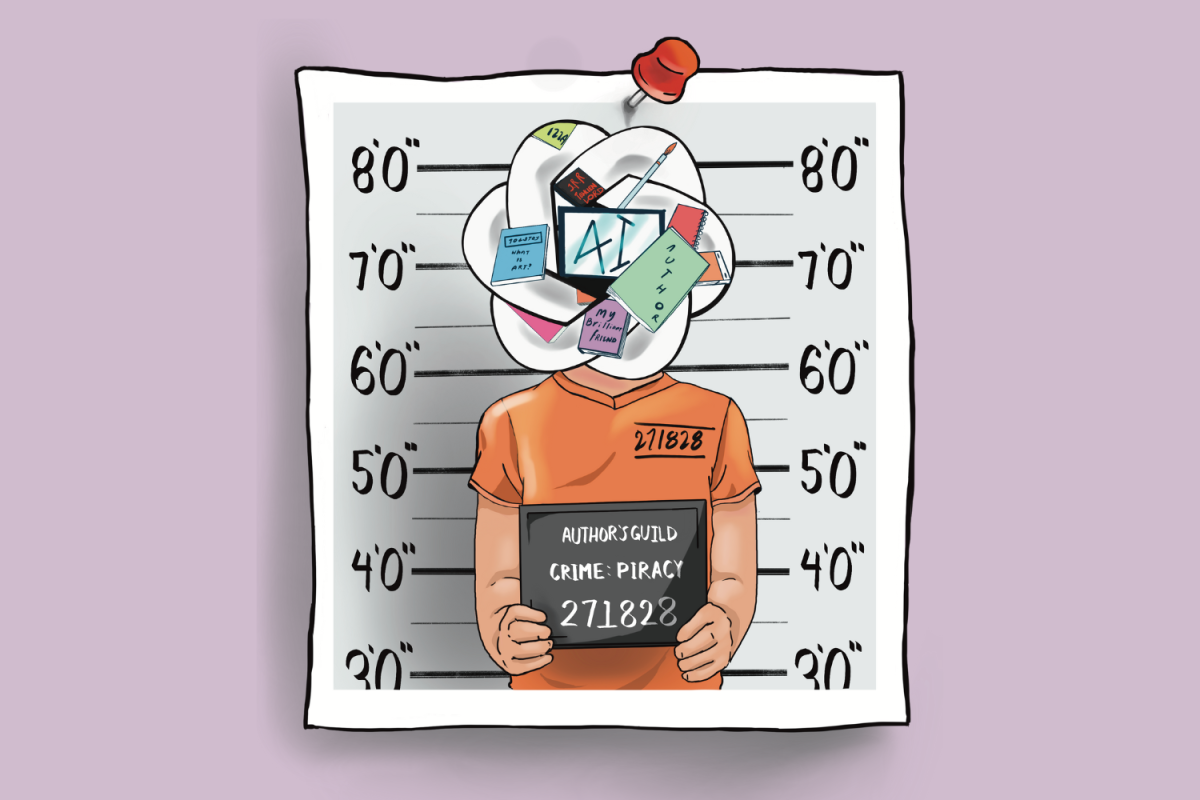

Yet, the power of satire does not come without pitfalls. The very aspects that make satire compelling — its use of exaggeration, irony and humor — also render it susceptible to misinterpretation.

In the era of fake news and rapid information dissemination, the line between satire and misinformation can blur, potentially misleading audiences. This underscores the importance of media literacy in society; understanding the nuances of satirical content can help discern its intentions and messages. When sarcasm and exaggeration are misunderstood by audiences who take them at face value, their intentions can backfire and cause confusion or backlash.

“Satire can be impolite; it can be vulgar,” said Erik Fredner, a University of Virginia postdoctoral research associate and lecturer who teaches a satire course. “But its excesses teach us something about society and culture: how far is too far? Social norms are not always written down, and satirists can reveal unwritten answers to that question through their art.”

Despite these challenges, satire presents familiar situations in a new light to challenge readers to reevaluate behaviors and societal norms, demonstrating its enduring power to provoke thought and inspire change.

“Satire will always have a place in a world that needs to speak out against injustice, hypocrisy and evil,” Fredner said. “In 2024, satire’s future is looking very bright indeed.”