While many of my kindergarten classmates went to lunch ecstatic and hungry, I went to lunch every day on a mission: to make a friend. My dad always advised me to make friends by following the other kids around and copying what they did, so I dug for “crystals” in sand filled with tanbark, pretended to know the lyrics of “Let it Go” and flipped around on the monkey bars, conforming with the other 5-year-olds around me. I was determined to someday discover the secret to making a friend, even with awkward English and an incessantly high-pitched voice. I have come to realize that learning to write was a form of compensation for my early troubles and sleepless afternoon naps, where dwelling on which conventional and conversational words I used served little help for the next awkward conversation I’d have.

When my first-grade teacher introduced “weekend writing” to us, I thought it was easy enough — I knew how to capitalize the first letter of each sentence, I knew how to dot my i’s and cross my t’s and I knew how to add a period to the end of each sentence. But it wasn’t just about grammar or penmanship as much as it was about a newfound consciousness. I took several minutes to think about each sentence I wrote, recalling my weekend dance class with my sister and the quick ski trips to Tahoe, erasing and rewriting words that would better fit the depiction of my memories. It was evident that the more I wrote, the more I could express my feelings in real life.

According to my teacher, writing was advantageous because anyone could take as much time as they needed to find the refined words and impeccable phrasing to articulate anything they wanted. Writing in school became my strong suit, since I embraced the endless time to think about forming my thoughts into words, and soon into well-developed essays and narratives. As I progressed through middle school, I learned to write about myself without compromising complexities.

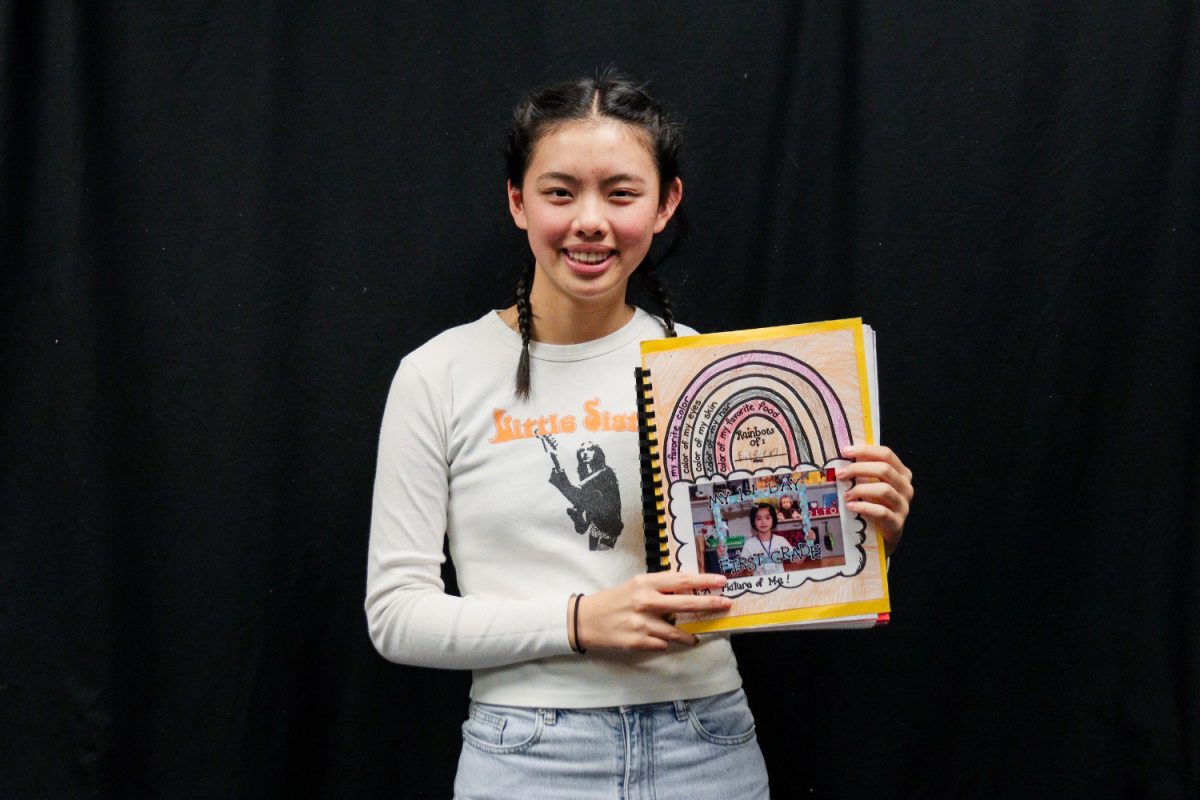

My days in early elementary school are blurry; I don’t have many recollections of specific events or favorite days and I wouldn’t be able to remember when I stopped worrying about my English. Without an iPhone camera or trendy digital photos to capture candid moments, most of us remember our childhoods with feelings. And so instead of wracking my brain to recollect moments of significance, I associate the early obscure moments with the words: excited, optimistic and often misunderstood, literally. Writing became a sanctuary where time was abundant, and so sentences were meticulously assembled into expressive tapestries, all eventually folded neatly into end-of-the-year portfolios.

A language barrier rained on some of my experiences as a kid, having to grapple with an invisible hurdle that isolated me from my classmates, but the beacon that writing could provide prevented the barrier from weighing down honest expression. Writing eliminates the endless possibilities of being misunderstood amid fast and frequent conversations, especially now that I feel inclined to Thesaurus my way through hazy thoughts.

So what makes writing different to me than speaking, now that I’m fluent in English? It’s easy to simplify and sacrifice honest emotions when we speak, whether it’s in the heat of the moment or a careless minute of small talk. If I guessed and checked words in and out of my sentences out loud the way I do when writing, I’d probably never catch a break or a breath.

After pushing past the misspelled words and scratchy handwriting from my collection of weekend writing entries, I’ve recently remembered what it was like to be five again — eager, anticipating and often dazed. I’ve found better vocabulary to describe, persuade and illustrate my thoughts over time, but it started with a want to be heard clearly.