Boycotts can work. We just think they can’t.

By Myles Kim

How do we know that boycotts work? Because we live in a country that was founded on them. Repeated economic boycotts of unfair British colonial policies gave birth to the American revolutionary movement, and those same principles of broad civil disobedience are what pushed African Americans to advocate for themselves during the Civil Rights era, molding this country into a more democratic and inclusive society. Today, the right to boycott and protest is almost synonymous with American political culture.

“I think boycotts send an important message to companies,” West Valley College political science instructor Jamilya Ukudeeva said. “That’s why companies are making sure that they’re ethical and that they pay attention to the culture of a particular society.”

The word “boycott” is derived from the name of the infamous landlord bootlicker, Captain Charles Boycott, who tried to evict farmer tenants during the Irish land war in the 1880s, for failing to pay their rent. In response, the community ostracized him, his laborers and servants abandoned their posts and his crops were left to rot. In this era of globalization, economic co-dependency and rising regional conflicts, Captain Boycott’s deserved demise teaches the grassroots organizers of today a crucial lesson: don’t mess with the working class. The single greatest unifying characteristic of the most effective boycotts throughout history are that they stem largely from grassroots and working class origins.

The Montgomery bus boycotts, and subsequent boycotts of motels, restaurants and other segregated establishments were not only initiated from a position of oppression and destitution; they succeeded in giving the civil rights movements the momentum they needed to continue their fight against discriminatory policies for the following 20 years. According to the National Park Service, over 90% of Black residents participated in the 381-day boycott, and it resulted in an estimated loss of 30,000 to 40,000 fares daily to the bus company. In fact, the boycott was so effective that leaders at the company were almost immediately willing to sit down to discuss the prospect of desegregating the transit system. However, due to pressure from city officials to retain segregationist policies, the company was forced to continue to endure a deficit of profits until the Supreme Court’s decision on Browder v. Gayle outlawed discriminatory policies in bus seating.

Three crucial lessons about the effectiveness of boycotts can be found in the outcome of the bus boycotts. One, that boycotts can be effective if highly directed toward one single entity or corporation; two, the momentum of a concentrated boycott is more likely to crumble from outside forces — such as a government seeking to preserve the status quo — rather than internal strife or conflict. Most importantly, the success of a grassroots social movement shouldn’t be wholly reliant on only one form of resistance or protest. Broad civil disobedience is crucial to the success of any social movement.

In today’s digital world, ripe with performative activism, the possibility of creating such a concentrated boycott effort is harder, but not entirely impossible. Empowered by one of the most potent culture war issues of this decade, transgender rights, conservatives seized on the marketing blunder that was the Bud Light and Dylan Mulvaney partnership, marking the beginning of one of the most successful boycott movements in recent American history. According to The Guardian, Anheuser-Busch, Bud Light’s parent company, suffered a $395 million loss in North American revenue in 2023’s second quarter as a result of the boycotts, and they ended up laying off 2% of its U.S. workforce — about 350 employees — in July 2023.

“A lot of people drink Bud Light,” Beth Demmon, author of “The Beer Lover’s Guide to Cider” said in a statement to The Guardian. “But at its core it usually appeals to white American men and represents a certain lifestyle. Football, nachos, BBQs, traditional suburban family dynamics, that sort of thing. It’s a stereotype that exists from years of very careful, specific and strategic marketing studies and campaigns, and it’s worked for a long time.”

There’s no doubt that boycotts can be an effective grassroots tool for progressive change. But like any form of protest, there are bound to be negative consequences — layoffs, shuttered businesses and unsatisfied consumers. While some may view these as inexcusable tradeoffs, the entire point of boycotts is to create that economic discomfort, which has been proven to have been able to force governments to submit to a movement’s particular demands. The conservative boycott of Bud Light demonstrates this economic discomfort through concentrated consumer activism, and the subsequent backpedaling of the company’s “inclusivity” initiative represents a conservative victory.

While the short-term objective of a concentrated boycott is to hit the targeted organization where it hurts the most — their money — the true battle lies in the discourse that can shape the public image of said organization.

In one of the most divisive and destructive conflicts of the 21st century, the Israel-Hamas war stands as the most recent testing ground for the effectiveness of boycotts. In January, Starbucks’ chief executive, Laxman Narasimhan, stated that the company had suffered a significant impact on traffic and sales in the Middle East, as well as a moderate loss in sales for their U.S. locations because of protests and boycotts. That being said, a moderate dent in the company’s short-term profits has not seemed to be able to force corporations to sever economic ties with or stop supporting Israel.

“Events in the Middle East also had an impact in the US,” CEO Laxman Narasimhan said during an earnings call in January. “Starbucks’ occasional US customers, who tend to visit in the afternoon, came in less frequently.”

In this case, there were many factors at stake that diluted the effectiveness of the boycotts. It is significantly harder for a concentrated boycott to form against multinational corporations like Starbucks, simply because their stores and branding are universally recognized. To have enough of an economic impact to alter Starbucks’ stance on the war would require a level of political and economic solidarity globally that is just not possible.

“Most important consumer boycotts often end up being unsuccessful,” Ukudeeva said. “However, when they do succeed, they manage to bring down the company’s reputation.”

While the boycotts may have seemed to have mixed results, the real victory of the pro-Palestinian movement lies in their ability to taint the public images of these companies permanently and flex their political clout to encourage change to occur. In California, many cities, such as San Francisco and Oakland, have voted on a ceasefire resolution; a handful of college campuses have also voted to divest from companies complicit in Israel’s war.

Some may argue that because of the inevitable harms that boycotts or protests can place onto working class individuals, one should resort to solely working within the means of our political system to enact change. Although efforts such as calling one’s representatives, signing petitions and voting are all good examples of working within the confines of our democratic process, good change has historically not come out of working within the system but rather pressure from the outside to force the system to act.

The 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, did not just happen overnight because Joe Schmo voted for a candidate that supported the women’s right to vote; or that the benevolent congressmen in power simply believed it was the “right time” to do so. It only happened because of decades of pressure from protests and boycotts, organized by women’s rights organizations. Attempting to solely work within the means of a political system that can barely function on its own is a lost cause, with lawmakers choosing to legislate on frivolous culture war issues, such as the TikTok ban, over what actually matters to most Americans.

In essence, civil disobedience and other related forms of protest from those outside the system push those from within to act and do the “right thing”. While boycotts can be a powerful bargaining chip, they should not be the only method through which one contributes to a social movement, rather they should be considered one of many tools that can be utilized to create social change.

Boycotts are a long-term strategy for protest. The ultimate success or failure of boycotts should not only be measured through a lens of the economic discomfort that a movement creates, but more prominently, the lasting impact of a movement’s message in the public town square.

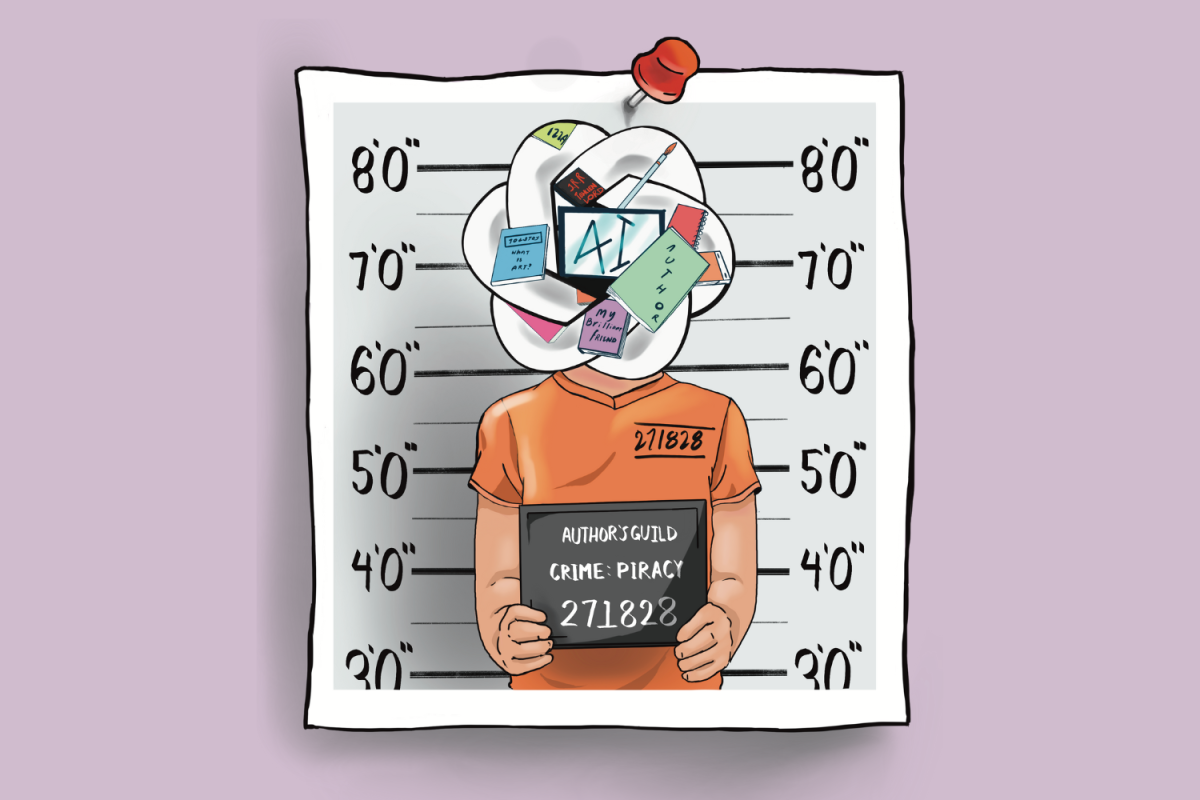

The adverse impacts of boycotting

By David Zhu

In recent decades, consumer boycotts, which occur in order to hurt companies for their stance on certain political issues, have gained traction. Thousands of people around the world use consumer boycotts to advocate for social and political issues that they are passionate about. However, in the process of advocacy, boycotters often fail to think about the destructive effects their boycotts end up having on the working class and consumers. Many boycotts in the past lack a sustained effort, proving to be ineffective. Rather than solely focusing on boycotts, advocates should take use of more methods including direct communication to their local, state-wide and national government offices.

The practice of boycotting was first recorded in the 1790s, when British abolitionists boycotted West Indian Sugar for its support of the slave trade. Since then, boycotts have been used to advocate for a variety of issues. According to Maurice Schweitzer, a professor of operations and information management at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, almost every major company has been boycotted at some point. In the past few months, boycotts against McDonald’s and Starbucks have rapidly grown in response to the conflict in Gaza. Boycotts easily gain online traction, and due to the vast amount of people using online platforms, these movements are able to grow in a relatively short amount of time.

“Lately, we’ve seen an increase in boycotts that became very popular,” Jamilya Ukudeeva, an instructor of political science at West Valley College, said. “Social media makes it easy to disseminate information, and there are no gatekeepers in terms of information, making these campaigns very easy to spread.”

The impact of boycotts are difficult and impractical to measure. In the past, large movements that wasted both energy and time ultimately resulted in little political and social change. For instance, when Chick-Fil-A was boycotted due to its controversy with the LGBTQ+ community, enough customers continued to eat there that it eventually outlived the boycott. It is impossible to quantify the amount of people and the time it takes for boycotts to significantly disadvantage a company.

“Very few boycotts have led to changes,” Schweitzer told the Los Angeles Times. “Most boycotts lack a sustained effort, and people lose interest or stop paying attention.”

In a comprehensive study by the University of North Florida on the impacts of consumer boycotts on Target firms, researchers found that only 24 of the 90 studied boycotts led to a minimal change desired by the boycotting group. The majority of these boycotts became too inconvenient and expensive to maintain.

“It’s often hard to measure the effect of boycotts on multibillion dollar companies,” sophomore and Politics Club officer Vikrant Vadathavoor said. “A lot of advocates are very reactionary and often forget about the social issue a few months later, and in the long term, some of these movements don’t help out that much.”

Although boycotts seem like an effective way to advocate for political issues, what’s often neglected are the numerous adverse effects they bring upon the working class. The interests of companies don’t necessarily represent the interests of their employees and the people that the organization serves. Thus, when companies are massively hurt by boycotts, the hundreds of thousands of people employed by the company are devastated by wage cuts and job loss. Many of these workers rely on the income from their jobs to support their families, and the layoffs will deprive these minimum-wage workers of their source of income. When boycotts against Target, Disney and Anheuser-Busch occurred, the companies themselves were largely unaffected while the employees bore the economic brunt. In the recent boycott against Starbucks, the company was forced to lay off 2,000 employees across many of its chains in the Middle East and North Africa.

Unfortunately, because many people from the younger generations join large boycott movements through social media, where the method of protest is to stop buying products from certain companies, less and less attention is being devoted to finding more effective ways to bring about substantial change. One of the most important methods of bringing about substantial policy change and a vital part of the US democratic process is voting, which a large portion of America’s youth is currently neglecting.

“Our voter turnout in America is one of the lowest among democracies, especially among the youth,” Ukudeeva said. “It doesn’t take a lot of time from your day to vote, to call, to write letters to government officials or to attend board meetings. It’s so easy, so make it a habit.”

Among the best forms of advocacy is direct communication with government representatives. In a survey of congressional staffers from the Congressional Management Foundation, in-person visits from constituents, individualized letters, email messages and phone calls have the most influence over government leaders. The power to make political decisions lies in the hands of government representatives, so when direct communication is established and they are influenced to act, the most impact is made. Overall, there are so many better methods of advocacy and protest in order to revolutionize the system that the public should prioritize rather than boycotting.

“A democracy requires its participants to put in their own work,” Ukudeeva said. “That means educating yourself. People need to invest their time to stay informed in order to make a change.”

Recent boycotts, which have resulted in massive layoffs for the working class reveal the dark side of political advocacy at the expense of workers who are just trying to provide for their families. Given the harms of boycotts, the public should search for better ways to advocate for the issues they are passionate about, such as taking the initiative to educate other people about the issue or contacting their government representatives. However, before even starting to advocate, boycotters need to make sure they are adequately informed about political issues, and avoid resorting to methods of advocacy that hurt the working class.