Across the street from Lynbrook’s main office, nestled among the trees in Rainbow Park is a building that many students see daily but may be unable to name. It’s the headquarters of Ethiopian Community Services. Though its presence may seem largely invisible, the organization’s impact on the local Ethiopian community, fueled by its devoted volunteers, is undeniable.

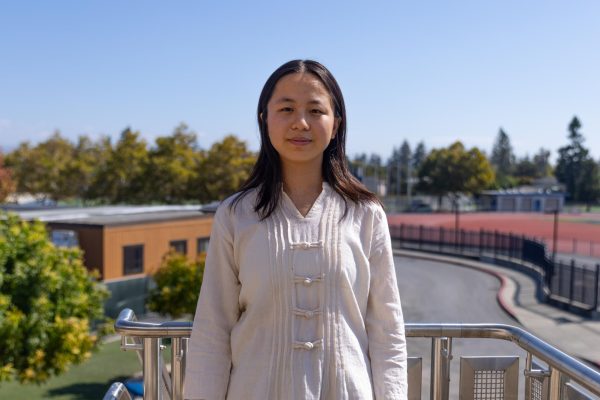

“We’re trying to serve every Ethiopian person in the community,” ECS board treasurer Menen Tesfahun said.

Founded in 1992, the nonprofit organization sought to support the growing number of Ethiopian immigrants settling in the Bay Area. The largest influx in migrants, fueled by growing political turmoil in the East African nation, began in the 1970s and continued throughout the 1980s. That surge in immigration continued well into the 1990s with the 1995 establishment of the Diversity Visa program, which selects entrants from an annual lottery to apply for United States immigrant visas. This program, coupled with the late-1990s rise of Silicon Valley’s technology industry, created incentives for immigration that made the Bay Area home to tens of thousands of Ethiopians — one of the largest concentrations in the nation.

Today, ECS continues to serve this population through a variety of programs and services. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, it partnered with community health centers and infectious disease experts to host a vaccine awareness campaign and informational webinars. In 2020, it also encouraged community engagement by educating local Ethiopians on the importance of voting and the census. One of its most popular ongoing services is its free 30-minute legal consultations, which are offered every other week by partnering lawyers.

Three decades after its inception, ECS remains a vibrant cornerstone of San Jose’s Ethiopian community, and has changed in several ways over the years. For example, its current board of directors consists of an unprecedented female majority and is led by the organization’s first-ever female president.

Yet, ECS has also contended with setbacks. The stock market crash of 2008 led to a permanent reduction of the generous aid money previously provided by a number of major donors, including the City of San Jose, which had allowed it to have paid employees. Unable to sustain that model, the organization’s capabilities were reduced to a fraction of what they were before. Numerous thriving programs, including a popular tutoring program for children in the community, were unfortunately discontinued.

“In the last four or five years, we managed to recruit more volunteers, but we’re still working to get back to where ECS was in the past,” ECS board president Mani Tadgo said. “The goal is to have a paid executive director and at least one program director, because the way it is right now is not sustainable.”

As ECS has changed, so has its community. The first generation of Ethiopians it served during its early years has now been joined by new generations of younger Ethiopians with different struggles and goals.

“The original purpose of ECS was to help the first generation, where there were language and cultural barriers,” Tadgo said. “The questions were, ‘How do they transfer their knowledge from back home to here? How can they participate in this environment?’ 30 years later, the second generation and beyond’s needs are changing. We’re working towards addressing concerns such as college access, mental health support and identity conflicts.”

The organization has responded to shifting demographics with several new initiatives aimed toward bridging generational divides, including computer literacy courses, Amharic — the official language of Ethiopia — lessons and an English as a Second Language program.

“We launched the Amharic lessons so that kids can learn the language and be able to interact with their grandparents and their family,” Tadgo said. “We want the youth to understand their culture.”

Amharic lessons are one of many ways ECS preserves and celebrates Ethiopian heritage. The cultural celebrations it hosts are pillars of unity, tinged with tradition, where community members can forge new connections through shared histories. For instance, at Coffee in the Park events in Rainbow Park, attendees can connect over shared cups of coffee, which is thought to have originated from Ethiopia and remains significant to its people’s heritage through customs like traditional coffee ceremonies. The event that sees the most attendees, however, is its traditional Ethiopian New Year celebration.

“With our community’s help, our sponsored businesses’ assistance and a few other organizations, our New Year celebration is the biggest event that we have,” Tesfahun said. “Since everybody gathers for that event, it is very festive.”

Through their ambition, passion and dedication, the volunteers of ECS hope to not only restore the organization to its past capacities but to propel it to new heights.

“Our dream is to make ECS bigger, to be more helpful for the community, to sustain ourselves with our own money and to hire people who can be open full time so we can continue to serve the community,” Tesfahun said. “Even if we’re helping only one person, we’re going to continue. We’re not giving up.”