A programmer sits, red-eyed, with dark eyebags and copious amounts of caffeine in their system as they stare at the blue light emitted from their computer screen, concluding yet another day of unpaid overtime because another company executive over-promised on a release date to shareholders. The production behind popular video games has recently gained notoriety for its toxic work environments and poor working conditions, prompting further examination into the extreme stress put on game developers.

“The people who participate in the video game industry, like Quality Assurance testers, developers, coders and artists, are very much driven by passion, “ said Ashley Parrish, a journalist who covers video games for The Verge. “This has tended to mean that they’re willing to put up with worse working conditions than what is typically acceptable, just for the“privilege” of working in the industry.”

Labor unions, which have long played a role in protecting the rights of workers, have been gaining traction within the gaming industry. Unionization rates in the video game industry have been traditionally low compared to similar industries. Advocates argue that unions would provide developers with a collective voice to negotiate fair wages, reasonable working hours and improved job stability, with 53% of game developers being in favor of forming unions. However, opponents of labor organizing in the industry often argue that the nature of the game development, with a project-based structure, may pose challenges to traditional union models and could have potential clashes with the creative and fast-paced nature of the gaming industry.

“Think of it like a sweatshop,” Parrish said. “They are working in a place for so many hours at a time doing a task and not necessarily being paid more for it, or the wages that workers are paid isn’t enough for the work they have to do.”

The constant hardships that workers are put through, such as long hours, harassment and low job security, has driven many to seek refuge in unions. A survey conducted in 2021 by the International Game Developers Association found that 32% of workers in the video game industry worked long hours, often without compensation. These game developers are victims of “crunch,” a term used to describe an industry practice of extended overtime with little compensation. Fifty-eight percent of employees, 64% of freelancers and 63% of self-employed workers reported that they had to participate in crunch more than twice in the past two years.

“I’d definitely feel a lot worse paying for games that had unfair working conditions behind them,” junior Kiriti Kotipalli said.

To be able to meet unrealistic release deadlines while still reaping a profit, companies often resort to finding loopholes to avoid paying their employees. EA Games, popular for games such as “FIFA”, “Star Wars Jedi: Survivor” and “The Sims,” was accused of illegally marking employees, who were owed money for crunch time, as exempt from payment.

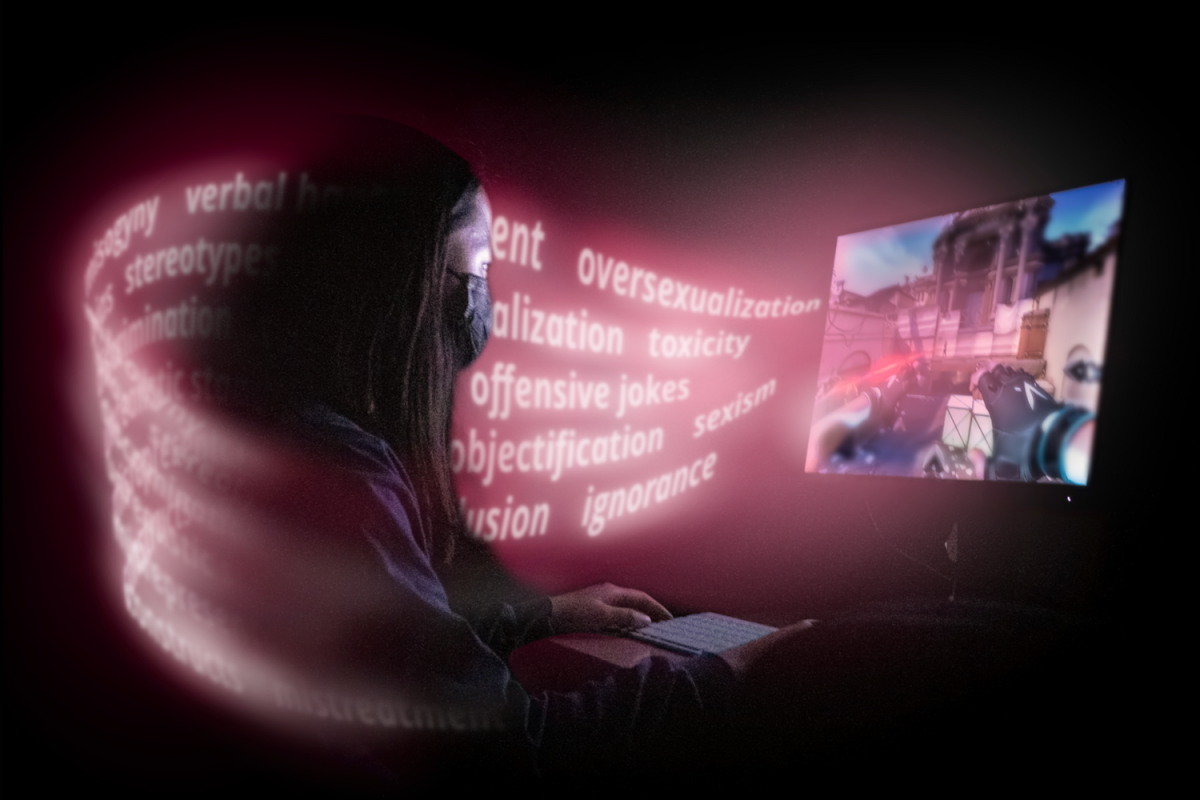

The gaming industry also has a history of sexual harassment, gender discrimination and ties to the #MeToo movement, prompting many to consider labor organizing to protect themselves. Ubisoft, a French company popularized by games such as “Assassin’s Creed” and “Just Dance,” gained notoriety when female employees came forward with allegations of abuse at its studios across the globe. In another instance, Activision Blizzard, famous for “Call of Duty” and “Crash Bandicoot,” was filled with sexual harassment lawsuits. The parents of Kerry Moynihan, a female employee at Activision Blizzard, asserted that the harassment by one of her male bosses played a significant role in her decision to take her own life. The company’s workplaces have been described as having a “frat house” culture by many of its employees. Employees under investigation for harassment were then forced to pay victims.

“Some companies are implementing zero-tolerance policies so that it’s clear that people who get reported for inappropriate behavior will immediately get fired,” Parrish said.

The push for better working conditions and gender equality started to gain more traction in 2019. Employees at a Los Angeles-based video game company, Riot Games, known for their competitive multiplayer games — “League of Legends” and “Valorant” — walked out to protest the forced arbitration of a sexual discrimination lawsuit filed in November 2018. Following the protest, Game Workers Unite was established later that same year as a group claiming to protect the rights of game developers everywhere.

More than one-third of video game workers were impacted by layoffs in 2023, which is more than 10,000 employees, including people in hundreds of California-based companies. On Jan. 22, Riot Games announced it would lay off 530 workers, or about 11% of the company’s global workforce because of a lack of investments. However, Riot Games provides at least six months of severance pay for employees who have been laid off and allows them to be eligible for cash bonuses.

Unionization has helped workers push for labor reform. Sega, a video game production company with over 200 workers most known for “Sonic the Hedgehog,” formed the largest multi-department union within the gaming industry, the Allied Employees Guild Improving SEGA. In July 2023, the National Labor Relations Board voted 91-26 in favor of the Sega Union. With over 200 workers, the creation of AEGIS-CWA has been touted as a massive victory by advocates.

“When buying a game with my own money, I always try to think about what the company has done ethics-wise before making any purchases,” senior and Asgardians Esports captain Justin Ngo said.

Sega began to push against crunch in 2013, trying to eliminate 100% of all enforced overtime. By 2018, crunch time was reduced by more than 80%. On Jan. 8, Sega announced that 61 workers would be laid off in March, and following the layoffs, the union will take steps to ensure the protection and representation of the workers, providing them what they need on a case-by-case basis.

While the game industry has had its problems with worker abuse, sexual assault and lay-offs, after much public criticism, companies have started to show more initiative in making their workplaces a safer and healthier environment. Insomniac Games, a popular game studio, made “Ratchet and Clank: Rifts Apart” with zero crunch hours, according to some claims by developers at the studio. “Marvel’s Spider-Man 2,” Insomniac’s most recent game, reportedly canceled features in the game to prevent extreme burnout and stress for its developers.

“If we want to improve working conditions, then we have to enshrine those protections in a contract and unionization is honestly the best way to do it,” Parrish said. “Also, calling out when developers or studios do bad things creates bad press, which can help ensure that things like that don’t happen again.”