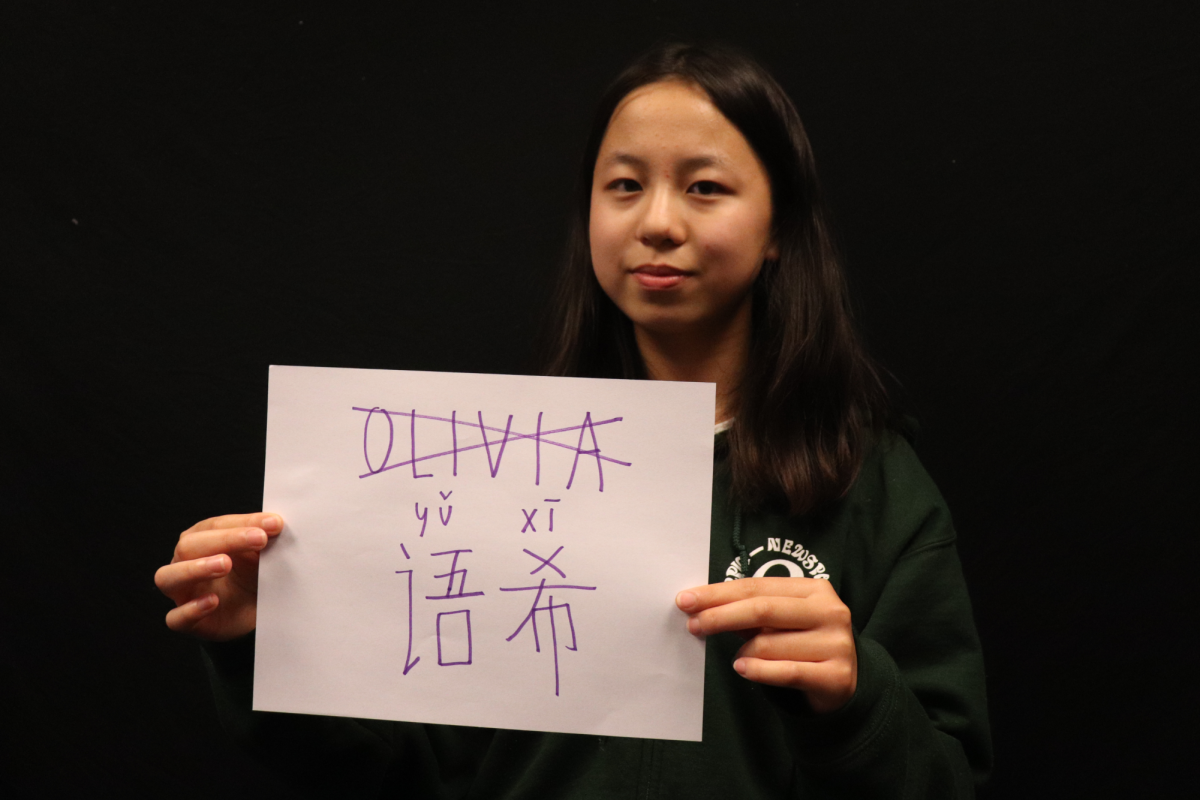

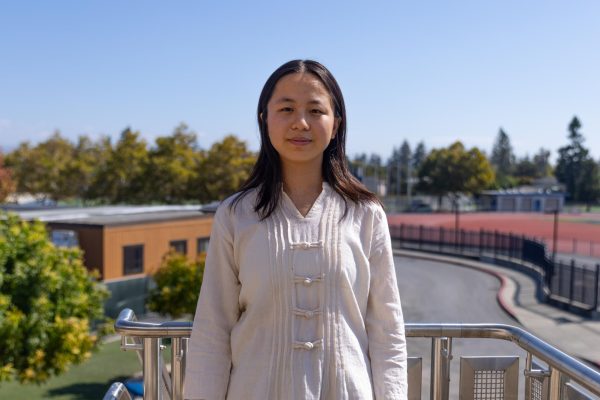

Olivia is the name my friends and teachers call me. For the most part, it’s an adequate definition of who I am. But it’s not the full story; in fact, Olivia began as an extension, added only to accompany me when my family immigrated from China to the United States. The very first name my parents chose for me, the one on my birth certificate, is Yuxi – yu (语) meaning “language” and xi (希) meaning “hope.”

I can still remember when speaking Mandarin came as naturally as breathing. It was an anchor to the Yuxi that stayed in China. Just as the blood of the people it belonged to flowed swiftly through my veins, the language flowed smoothly out of both my mouth and pen. As the years passed and I grew more comfortable in English, I learned to deftly weave in and out of the two languages, switching between them in a heartbeat.

But three years ago, everything I thought I knew about Mandarin – and about myself – changed. It became my breath catching in my throat and my heart pounding in my ears, a hesitant pause that seemed volumes louder than the shoddy scramble of Chinese phrases that followed. Suddenly, it was English I relied on as a crutch to supplement my Chinese, not the other way around.

As the time I spent with my Chinese roots and family diminished during lockdown, so did my years of knowledge and experience. Chinese class, which I used to enjoy, became a graveyard for the words that died on my tongue. Every toneless pronunciation and missing particle, every incomplete sentence and unknown character, widened a gaping absence.

By quarantine’s end, guilt had withered my desire to amend inaction and begin anew. I was ashamed that I had let such an essential part of me simply crumble away without even trying to salvage the pieces.

With high school came a slew of resources to prepare me for college, including the AP Chinese exam. But instead of being yet another reminder of my betrayal, I saw the exam as an opportunity for redemption. Having spent the past two years navigating the tangled mess of my fractured identity to little avail, I welcomed the tangibility of the road to success.

The first few weeks of the preparatory class were daunting. But seeing my classmates engaging and progressing, despite their trepidation and unfamiliarity with the AP-oriented course structure, motivated me to do the same. I took full advantage of the opportunities at my fingertips, from my place in the classroom alongside my peers to a range of Chinese media I hadn’t consumed since childhood.

Once I swallowed my initial hesitation, it was as if a dam had broken. I threw myself into speaking and immersing myself in Chinese with a new resolve. Words I thought I had long forgotten resurfaced. The first conversation I struck up with my parents entirely in Mandarin, a product of genuine interest and not expectations or etiquette, felt like coming home.

The more I allowed myself to engage, the easier it became to continue. I still have a long way to go in regaining the fluency I once took for granted and reconnecting to the culture I left behind, but now that shame and guilt no longer hinder my progress, I know it is within reach.

When I severed ties with and drifted away from my language, I lost sight of my history and culture. I felt so distant from my first identity and Yuxi, the name that had defined it, that it seemed like I would never recover the person I used to be. But she never truly disappeared, and by finding the courage to relearn Mandarin, I found my way back to her. I should have known from the start – language and hope would not vanish so easily.